A recent review by orthopaedic oncologists and pathologists from Vanderbilt University Medical Center and the Cleveland Clinic provides an updated overview of best practices for evaluation of surgical margins in cases involving bone and soft tissue sarcomas.

Surgical margins are a primary metric of success in cancer surgery in this specialty, so understanding the significance of the integrity and width of margins is crucial and ongoing, said Joshua Lawrenz, M.D., assistant professor in the division of musculoskeletal oncology at VUMC.

“Surgical resection is the predominant treatment for extremity sarcoma, and achieving a negative margin is a primary goal,” Lawrenz said. “However, it is not a one-size-fits-all mentality when evaluating what makes a good margin.”

The team’s report, published in The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, focuses on margins and their classification systems. The four pathologists contributing to the paper provide commentary on the technical aspects of intraoperative and final margin assessment. New techniques and technologies, which have greatly changed surgery and outcomes, are also surveyed.

“The idea for this review article came from clinical conversations within our practice,” Lawrenz said. “This paper represents the consensus from sarcoma surgeons and pathologists at our two centers.”

Examining by Sarcoma Type

Much of the discussion involves data in various types of sarcomas:

- How should a surgeon determine the size of the margin?

- What happens if there are positive margins?

- How do the margins differ for osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma and chondrosarcoma, the three main types affecting bones?

- And what about the soft tissues?

“We try to draw conclusions about these tumors as a group, but also examine certain types individually,” Lawrenz said.

The significance of a single millimeter in a given margin can change according to the patient and circumstances, for example, whether other structures sit alongside the margin.

“The proximity of nerves, blood vessels or key structures can complicate this goal,” Lawrenz explained.

To retain or restore the best function to an affected limb, surgeons seek to completely remove the tumor without major negative impact on the patient.

“Removing cancer is the most important objective; that’s why we sometimes have to amputate,” Lawrenz said. “Though in most cases, our goal is limb-salvage surgery – removing the tumor while preserving the limb.”

“In many cases, our goal becomes limb-salvage surgery – remove the tumor, then reconstruct.”

Advancements in chemotherapy and joint replacement have significantly changed treatment goals and surgical approaches. Before 1970, amputation was the most common treatment option for extremity sarcoma, with poor overall survival, the surgeon said.

For a tumor associated with neurovascular invasion, the margin may by necessity be narrow, and in these cases, tumors are often particularly aggressive.

Best Practices Updated

Adjuvant therapies also affect decisions regarding the margin. By shrinking the tumor and sterilizing the field, chemotherapy and radiation therapy have greatly improved outcomes in these cases in recent decades.

Advanced technologies such as surgical navigation and fluorescence-guided surgery are also working toward improving outcomes in achieving negative margins.

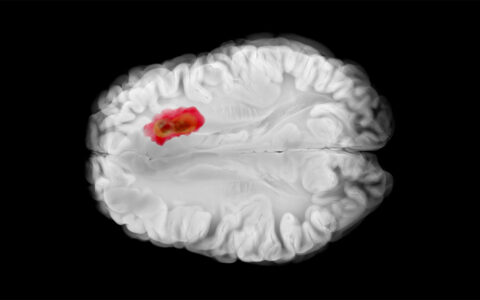

“At Vanderbilt, we’ve worked with Dr. Michael Topf, scanning specimens to create three-dimensional mapping of margins. Previous methods can seem inadequate or even archaic by comparison.”

Lawrenz said the information will be helpful for orthopaedic oncology specialists, who treat cancer in a variety of anatomical locations.

“We often need to resect a three-dimensional, sometimes amorphous mass, located in a limb or pelvis. There are a variety of shapes, sizes and locations. It requires a nuanced and comprehensive view of how these surgeries should be performed. The paper addresses these issues.”