Craniosynostosis occurs when there is a premature fusing of a baby’s skull bones, a singular definition that encompasses a wide range of related conditions.

Until 2024, the international diagnosis classification system known as ICD-10 addressed craniosynostosis as just that, using a broad umbrella designation with no subdivisions. Yet, from the more common sagittal fusion to rarer complex syndromic fusions, treatment and its timing can vary considerably.

The situation has left doctors grappling with misalignments between existing ICD-10 codes and codes used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) when dealing with insurers. It also has created a significant obstacle for researchers as they tried to compare conditions and procedures.

“Grouping the different kinds of craniosynostosis together did not make sense medically. Now, we will have a means of tracking patients to enable research and better-informed conversations with parents about the surgical options.”

Now, amendments to the ICD-10 codes will add seven distinct subcategories under the craniosynostosis code of Q75 and two under Q67 thanks to the work of pediatric craniofacial neurosurgeon Christopher Bonfield, M.D., and craniofacial plastic surgeon Michael Golinko, M.D., at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt. They worked with two colleagues at Boston Children’s Hospital on advising the CDC on its new, more finely delineated coding.

“Grouping the different kinds of craniosynostosis together did not make sense medically,” Bonfield said. “The patients aren’t treated the same way, and they have different outcomes. Now, with the subdivisions, we will have a means of tracking patients to enable research and better-informed conversations with parents about the surgical options and what to expect.”

Golinko called the changes “intuitive.”

“As far as a workflow goes, it’s actually very simple. It doesn’t take up any more clinician time, but it has huge implications down the line.”

Severity Variations

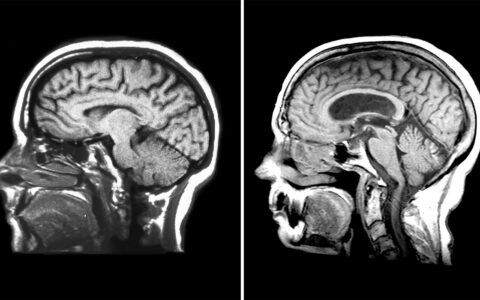

While the different forms of craniosynostosis threaten brain growth by impeding the growth of the skull, the location of the impairment and its treatment vary widely, depending on which sutures are fused, Golinko explained.

He notes that treatment for the most common form, sagittal fusion, tends to be the most straightforward and enables normal growth and good outcomes. At the other end of the spectrum are the syndromic forms, where a number of sutures may be fused. These patients often require multiple surgeries, and contextual considerations of heart, lung and neurodevelopmental anomalies also come into play.

Subtypes

To develop the new ICD-10 subcategories, Bonfield, Golinko and team met several times with the CDC’s Coordination and Maintenance Committee and raised attention in the literature before the code changes were adopted in the fall of 2023.

The new Q75.0 codes cover the four single-suture conditions: sagittal, in which parietal bones at the top of the head are fused; coronal, a horizonal fusion of the parietal and frontal bones; metopic, a fusion of the frontal bones down the center of the forehead; and lambdoid, a parietal and occipital bone fusion at the back of the head. Some of these are broken down into a choice of unilateral, bilateral or, when the original suture pattern is unknown, unspecified.

A separate category exists for multi-suture craniosynostosis, which are further subdivided by the main patterns seen in this condition, such as the cloverleaf pattern of fusion. Two additional categories were created for deformational, non-craniosynostosis subtypes: dolichocephaly and plagiocephaly.

Building Predictive Tools

Bonfield says that the gains for research are the biggest win. With the accrual of outcome data by subtype will come the chance to erase some of the many gray areas in clinical practice.

“You have these options when an infant shows up in clinic at one month of age: Do you operate then or wait?” Bonfield explained. “There are questions about whether anesthesia is harder on them when they’re younger.”

Questions also linger around cosmetic and developmental outcomes based on a patient’s age at surgery.

Generally, surgeons will operate on every child with the condition because they don’t know which considerations to apply to which type, he said.

The Vanderbilt duo has multiple research efforts underway, including examining serum biomarkers in babies’ blood for signs of brain injury, using novel imaging to see which children might be at higher risk of future brain injury, and applying machine-learning to better characterize head shape for these babies.

Golinko said their team also is seeking an NIH grant to create a human craniosynostosis atlas to better characterize the condition through neuroimaging and genetic markers. They would make the repository available to the scientific community.

“All these research efforts, taken together, will help us track these children’s brain changes and discern whether the operation is expected to change head shape, affect brain health, or both,” Golinko said. “Some children will have delays despite surgery, and others will be completely normal. With the improved classification across the board, research across multiple centers will be greatly facilitated, which is critical in a rare disease that affects one in 2,000 children each year.”

Cause to Celebrate

Last fall, Bonfield, Golinko and their colleagues took the podium at the International Society of Craniofacial Surgeons biannual meeting in September 2024 to explain the change.

“We wanted to spread the word that this is coming, and that it is a good thing,” Bonfield said. “All the craniofacial surgeons and neurosurgeons are excited about it because it doesn’t add more work, and now they can categorize their patients and offer them more personalized recommendations.”