Carlos M. Mery, MD, is Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s chief of pediatric cardiac surgery and co-executive director of the Pediatric Heart Institute at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt; Ziv Beckerman, MD, is the associate chief of the pediatric heart transplantation and adult congenital heart surgery programs. We recently sat down with both leaders to discuss VUMC’s investment in transforming care across the lifespan for patients with congenital heart disease.

A ‘Vision for Lifelong, Holistic Care’

Question: Dr. Mery, you came to Vanderbilt in October 2024 to serve as chief of the congenital heart disease program. What was the vision that drew you here?

Mery: I have worked with colleagues at other centers to build top programs, and Vanderbilt is making the kinds of investments in congenital heart disease care that convinced me we could reach their vision for lifelong, holistic CHD care at the very highest level found anywhere.

Vanderbilt has one of the oldest congenital heart programs in the United States and one of the things that’s been unique here is the integration of the pediatric and the adult side within the same organization. This has allowed us to think about clinical programs in a different way, asking how we build a program that takes you from early life all the way through late adulthood, cares for you as an individual, and provides you with all the resources that you need to have that longitudinal care.

Question: Dr. Beckerman, you worked with Dr. Mery at two of these other institutions and on your own were a leader in elevating one of the top programs. Why did you say “yes” when you were approached by Vanderbilt?

Beckerman: That investment in the mission to build a program that provides patients with comprehensive, longitudinal care and that cares for the patient as an individual drew me.

Congenital heart surgery can be curative at times, but frequently, patients will require more than one operation or intervention throughout their lifetimes. Our goal is for them to feel and do great through life, in between the time that they require interventions. We want them to grow up in a way that allows them to feel normal, and reach the next phase of care before they’re too sick.

Question: How would you characterize the investment Vanderbilt is making?

Mery: Our mission requires investment in all the pillars of cardiac care: in the people, in the program itself, in our operating room and intensive care programs. This includes specialized equipment, remote monitoring systems and a multidisciplinary team of surgeons, cardiologists, intensivists, anesthesiologists, perfusionists, nurses and other personnel that function together at the highest level.

The goal is to always surround patients with comprehensive expertise, ensuring no patient needs to be referred elsewhere for care.

“The goal is to always surround patients with comprehensive expertise, ensuring no patient needs to be referred elsewhere for care.”

The Significance of ‘Lifelong Care’

Question: What does providing lifelong care entail?

Mery: Historically, we would only measure things like mortality, readmissions and other clinical outcomes. Now we are focusing, as well, on learning and measuring the outcomes that are most meaningful to patients and families. Not to us but to them. What makes them feel that they have their own best life journey.

Beckerman: Lifelong care involves not only caring for the heart/body, but providing patients and their families the required education to succeed in life. When patients turn about 9 or 10 years old, it’s important to start educating them about the fact that they need to take care of themselves and own their health. I had a 13-year-old girl recently, where I sat with the family and said, “You are my patient. Your parents are here, of course, to support you, but this is your body and you need to take responsibility for your health.”

The earlier you educate them towards that, the better. And what those kids start doing is unbelievable—they will remind their parents about their medication, and focus on a lifestyle that will make their health and their lives successful.

Question: What structures are in place at Vanderbilt to help across the lifespan?

Mery: We believe that the way to reach our goals is by surrounding the patient with all the specialties, all the care that they can possibly need, at all times.

We have an amazing team of pediatric and adult congenital cardiologists who follow our patients through life, all within our system. For patients with single-ventricle heart disease, some of our most complicated patients, we have a dedicated cardiologist, Jamie Colombo, DO, who works with them during infancy and early childhood. Patients then transition to our full-time Fontan Clinic run by CHD cardiologist Angela Weingarten, MD. The clinic has a psychologist, occupational therapist, nutritionist and more resources to support patients through various stages of their lives. Currently, they are launching a virtual support group to bring patients together.

We recently recruited Andrew Well, MD, MPH, an expert on patient-centered care, who has done a lot of work on assessing the lifelong journey of patients with congenital heart disease and creating initiatives to improve that care.

We are now training our fifth fellow in adult congenital cardiology. Whether they remain at Vanderbilt or go elsewhere, we want to expand our capabilities to meet the rising demand as more people with congenital heart disease live and thrive.

Improving Outcomes

Question: Are there particular surgical advancements you are looking at now that may make a big impact on survival and quality-of-life outcomes?

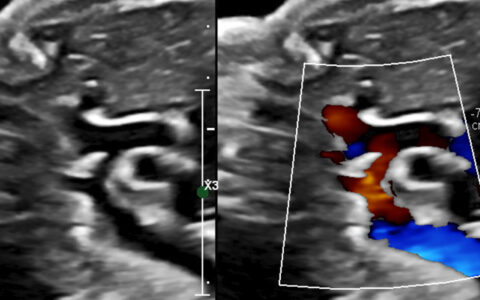

Beckerman: There are a number of advances in the field of congenital heart surgery. Perhaps the most recent one is implantation of living roots and valves. One particular operation is the living Ross procedure/partial heart transplant. This is the only valve replacement option to date that had the potential to provide patients with valves that can grow with them. And spare certain patients from repeat valve replacement surgeries.

I started doing this three years ago as part of my prior institution. Patients with dysfunctional pulmonary or aortic valves typically get homografts from cadavers. But these aren’t able to grow, so replacements are needed, anywhere from one to 15 years after the initial replacement. The living Ross operation, for example, involves taking the patient’s pulmonary valve and moving it to the aortic position (instead of his dysfunctional aortic valve) where it can grow with the patient. The pulmonary valve is then replaced with a living donor pulmonary valve that can, in theory, also grow with the patient.

We believe these valves have the potential to last a lifetime. Despite the complexity of such an operation, we perform this with an expected complication rate of less than 1%.

Mery: You don’t just do some special procedure you know how to do. You adapt and provide the patient the specific treatment they need. Our surgeons are subspecialists in multiple procedures, so we can perform a spectrum of surgeries that not many places can provide. Plus, Vanderbilt attracts the volume needed to be great.

But that this is not all. The surgeon matters but most important, the program matters. I tell patients to look beyond the surgeon and look at every element of the program that is going to care for their child. That’s also why we have put so much emphasis on continuously improving every single piece of the program so we can provide the best possible care for their child at all times. That’s the scope of our mission.

“That’s why we have put so much emphasis on continuously improving every single piece of the program so we can provide the best possible care for their child at all times. That’s the scope of our mission.”