A 27-year-old woman with a congenital exstrophic bladder and extensive surgical scarring, adhesions and complex anatomy came to Vanderbilt University Medical Center in early 2021 with a severe ureteral stricture. Rather than remove a kidney, two surgeons teamed up on a customized procedure that saved her kidney, created a functional ureter and restored urine flow – with low morbidity and a three-day recovery.

Vanderbilt surgeons Nicholas Kavoussi, M.D., an assistant professor of urology, and Aimal Khan, M.D., an assistant professor of colon and rectal surgery, credit their success to a history of collaboration and expertise in robotic surgery. “Most people would have removed the kidney or opened this patient up from chest to pubis to perform a complicated reconstruction,” Khan said.

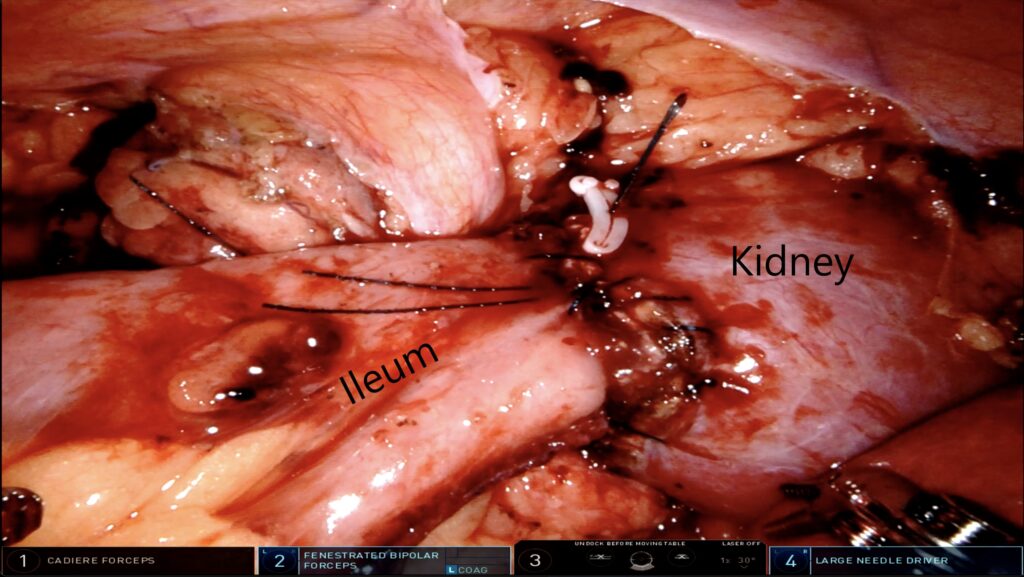

“By using robotics to harvest small bowel tissue and connect it to her existing repurposed bowel tissue and the kidney, we were able to avoid that irreversible option in a minimally invasive manner,” Kavoussi said.

Surgical Landmines

Bladder exstrophy, a congenital condition where the bladder and related structures are everted through the ventral wall of the abdomen, occurs in one in 50,000 births. Surgical repair in infancy is not uniform and is widely understood to be extremely complex.

“When this patient was a young girl, she went through multiple reconstructive surgeries and ultimately ended up with an augmentation of her bladder using bowel tissue,” Kavoussi said. “Her ureteral scar tissue was extensive, involving most of her proximal ureter and renal pelvis where the kidney widens.”

The patient had a BMI over 30 and a history of kidney stones. Her (right) ureteral stricture was five centimeters long. “Had it been a short stricture, we could have cut the scar tissue and plugged the ureter back into itself,” Kavoussi said. To enable a workaround for draining urine, she had a nephrostomy tube percutaneously draining urine from her kidney and had been catheterizing through her umbilicus since she was child.

Her multiple prior surgeries complicated the planning. “Lots of times when we do reconstructions, we utilize the renal pelvis to make flaps that help constitute the new ureter during our reconstruction. But with all the scar tissue leading up to the renal pelvis, we couldn’t do that,” Kavoussi said. The fact that one bowel graft had already been harvested to reconstruct part of her bladder represented a further complication.

“We were able complete this surgery using only seven incisions, each under a centimeter. This is truly a minimally invasive surgery, with much less pain, faster recovery, and a lower risk of infection or hernia.”

Additional planning challenges had to be met. The renal pelvis, where the ureter normally attaches, had been scarred in a past surgery, leaving no patent opening for attachment. Another concern was that the patient had a previous bowel graft procedure that connected her ileum into her bladder (to increase its capacity) and that used her appendix as a drainage tube from her bladder to umbilicus. “These prior surgeries distorted her GI anatomy, adding to the complexity of an already challenging surgery,” Khan said.

The Ileo-calycostomy

The conventional option would have been to remove the kidney, eliminating the need for major reconstruction. The patient, however, wanted to keep both kidneys. To save the at-risk kidney, which filtered about 40 percent of her blood, the team tackled the challenge of harvesting more bowel and creating an ileal ureter.

Kavoussi and Khan performed the day-long procedure from two robotics stations. It began with the bowel harvest. “The challenge for me was to try to identify a healthy, 20-centimeter piece of bowel, detach it from the GI tract, and mobilize it toward the kidney,” Khan said.

In parallel, Kavoussi was working to expose the targets on the kidney. Once the graft was positioned, he removed the bottom 15 percent of the kidney. “I widened the base to reduce the risk that mucus produced by the ileal tissues would plug up the conduit,” he said.

“We were able complete this surgery using only seven incisions, each under a centimeter. This is truly a minimally invasive surgery, with much less pain, faster recovery, and a lower risk of infection or hernia,” Khan said.

A Definitive Treatment

The procedure restored the patient to her customary elimination through the umbilical region, without indwelling tubes, and supplied what the surgeons hope will be a definitive treatment.

Three months later, the patient is thriving and free of any nephrostomy tubes in her back. “The risks now are that she will develop mucus plugs or a potential blockage from scarring at the anastomotic site as her kidney changes over time,” Kavoussi said. “If she is going to have a big problem, it would be in the first couple of years. After that, we would expect her to be in the clear.”