Glucose response to a meal is affected by genetic variation in the gene encoding the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor (GLP1R), according to recent research published in Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism.

The study reports that individuals carrying the GLP1R rs6923761 variant – a specific G-to-A nucleic acid substitution on one (GA) or both (AA) alleles – have increased markers of insulin secretion and decreased glucose excursion after a meal compared to GG individuals. The authors also found that individuals carrying the rs6923761 variant display a reduced response to the antidiabetic medication sitagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor that modulates GLP-1 levels.

“It seems to be a drug-gene interaction, whereby the beneficial effects that you get from having the GLP1R variant cancels out the beneficial effects of sitagliptin,” explained Mona Mashayekhi, M.D., first author on the study and an instructor in the Division of Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

The findings support the need for further research into the relationship between GLP-1 receptor genotype and therapies that modulate GLP-1 signaling, particularly as this class of agents becomes more broadly prescribed for type 2 diabetes.

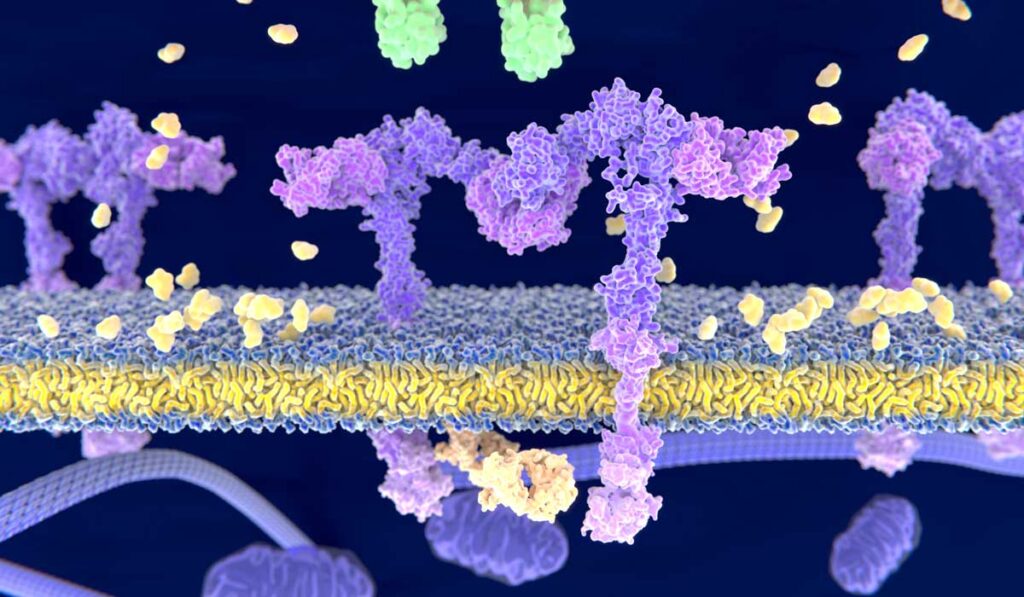

Modulating GLP-1 Signaling

GLP-1 is an incretin that increases insulin secretion by binding to GLP-1 receptors. The GLP-1 signaling pathway is tightly regulated in part by the enzyme DPP-4, which rapidly degrades GLP-1. DPP-4 inhibitors can be used to treat diabetes, as their ability to prevent GLP-1 degradation boosts insulin levels.

“It seems to be a drug-gene interaction, whereby the beneficial effects that you get from having the GLP1R variant cancels out the beneficial effects of sitagliptin.”

“DPP-4 inhibitors have been approved for use in the treatment of type 2 diabetes for about 15 years,” Mashayekhi said. “They are an alternative oral pill agent, typically used for patients who are not yet on insulin.”

Modulating GLP-1 signaling is also the approach of another class of antidiabetic agents, GLP-1 analogues. “GLP-1 analogues as a class do a better job of lowering blood sugar as compared with DPP-4 inhibitors and provide protection against a lot of the adverse outcomes seen with diabetes, such as cardiovascular disease,” Mashayekhi said. Until recently, all GLP-1 analogues were administered by injection, which made them less attractive for some patients. An oral form of this drug has recently been approved by the FDA.

Too Much of a Good Thing

In the new study, Mashayekhi and colleagues assessed whether genetic variation in GLP1R affects the metabolic response to DPP-4 inhibitors after a meal. Participants with hypertension and type 2 diabetes were treated for seven days with placebo or sitagliptin and then presented for a standardized meal. The genotype frequency of study participants was 13:12:7 GG:GA:AA.

As expected, sitagliptin decreased DPP-4 activity and increased intact GLP-1 across all genotypes. “We saw what we expected to see; sitagliptin is working as an antidiabetic drug and you don’t get as much of a rise in glucose after a meal,” Mashayekhi said. “The novel discovery was a differential response to the mixed meal based on GLP1R genotype.”

Regardless of treatment, postprandial glucose excursion was significantly decreased in GA or AA allele carriers compared to GG allele carriers. In an additional twist, sitagliptin was less effective at lowering postprandial glucose in GA or AA individuals compared to GG individuals.

“This has been seen in two prior studies, where DPP-4 inhibitors did not lower blood sugar as effectively if patients had this GLP1R variant,” Mashayekhi said. “While those studies demonstrated a negative impact of this variant on responses to DPP-4 inhibitors, I think our study highlights the underlying physiology whereby having the variant confers a baseline metabolic advantage, and the addition of a drug like sitagliptin does not have much added benefit.”

GLP1R and Gastric Emptying

Mashayekhi and colleagues have now turned their sites on testing whether genetic variation in GLP1R also influences gastric emptying, which has been suggested in the literature.

“The rapidity with which nutrients pass through the gut can affect how well glucose is handled by the body,” she explained. “If things are passed more slowly, you’re allowing more time for the glucose absorption to be matched with your insulin secretion.”

“We saw what we expected to see; sitagliptin is working as an antidiabetic drug and you don’t get as much of a rise in glucose after a meal.”

“It is an attractive hypothesis because we know that GLP-1 analogues delay gastric emptying on their own, that’s one of the mechanisms by which these drugs work to cause weight loss and lower blood sugar,” Mashayekhi added.

She emphasizes that as providers and researchers push for more personalized approaches to medicine, it will be important to keep in mind how the genetics underlying a patient’s physiology interact with the pharmacology prescribed on top.