A high level of support for smokers who are trying to quit markedly increases their success – especially for those whose bodies metabolize nicotine quickly, according to a recent study published in Nicotine and Tobacco Research.

“There is a marked disparity in smoking cessation between fast and slow metabolizers, but we can cut the gap in half with enhanced support for the fast metabolizers.”

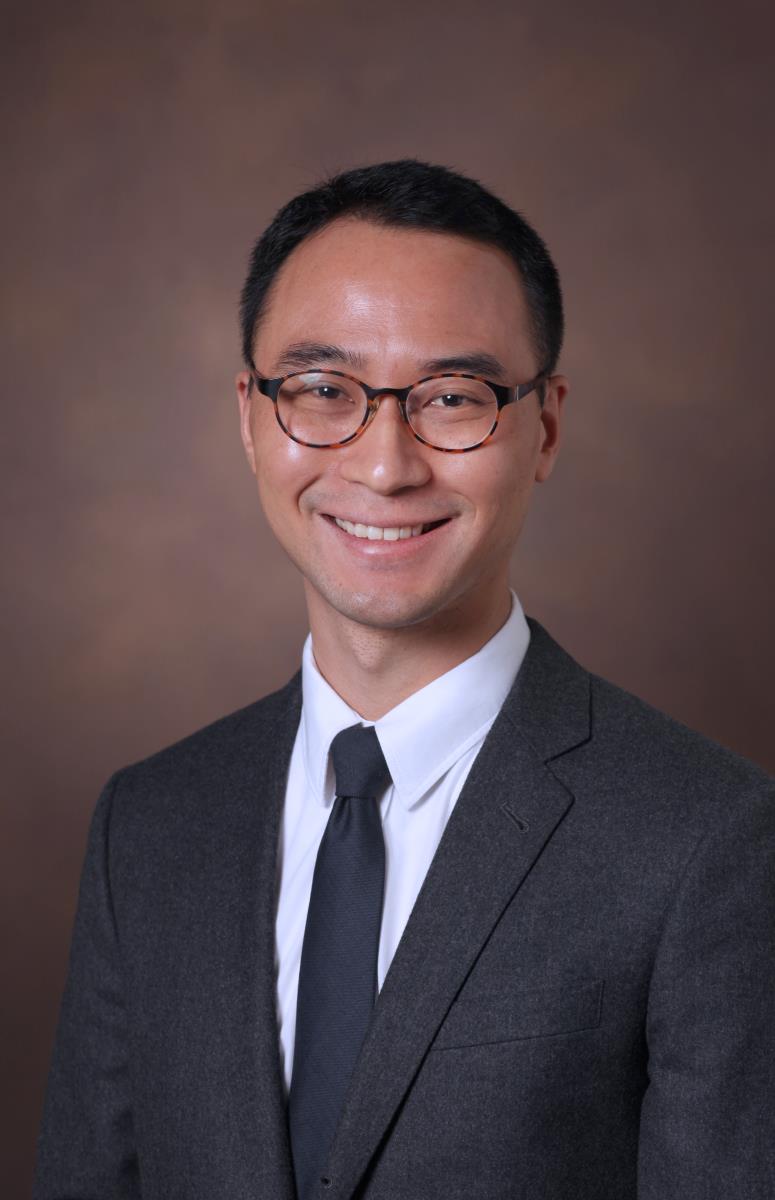

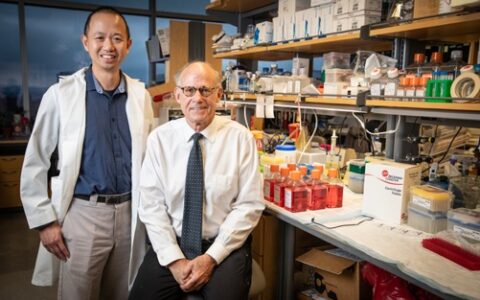

“The rate at which the liver metabolizes nicotine has been identified as a key biomarker called the NMR,” said Scott S. Lee, M.D., Ph.D., the article’s first author, an assistant professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. “It’s been clear that faster metabolizers, who represent a large majority of smokers, have a harder time when they try to quit.”

The new study compared cessation outcomes by the participants’ nicotine metabolite ratio (NMR). About two-thirds to three-quarters of smokers are fast metabolizers, Lee explained.

“There is a marked disparity in smoking cessation between fast and slow metabolizers, but we can cut the gap in half with enhanced support for the fast metabolizers,” Lee said. “We saw this when we gave them medication to quit smoking in hand when they left the hospital and then provided personalized, human counseling.”

Taking a Different Tack

The research team worked with 321 daily smokers who had been hospitalized at Vanderbilt. Eighty were slow metabolizers and 241 were fast metabolizers, as determined by their NMR. The investigators assigned each smoker, upon discharge, to receive either the usual level of care for smoking cessation or enhanced treatment support.

“Other studies that have taken the NMR into account when treating tobacco use have kept the ancillary support the same and varied the medications, which include nicotine patches and varenicline, an oral medication,” Lee said. “We flipped that. We kept the medications the same – everyone received nicotine replacement therapy – but varied the ancillary support.”

He noted that smoking cessation interventions are known to be most effective when they include both medication and counseling support.

Quitline Referral per Usual

In this study, control participants received a typical quit-smoking prescription: referral to the state Quitline, a telephone-based resource available throughout the United States to support smoking cessation. The Quitline then offered the patients 14 days’ worth of nicotine replacement therapy, in the form of either patches or lozenges, as well as telephone counseling.

“The usual-care arm mimicked what usually happens among discharged patients who smoke,” Lee said.

In this model, a Quitline places an initial call to each patient after their discharge but requires them to opt-in for opportunities to talk further with counselors. The Quitline stops calling if there is no answer after several tries.

Enrollment Automatic

Patients receiving enhanced support were provided at no cost to them a combination nicotine replacement therapy – that is, both nicotine patches and gum or lozenges – at the time of hospital discharge. They were also automatically enrolled in a computerized system that the research team developed to follow up with them after discharge.

“Those patients received multiple automated calls at prespecified intervals, starting three days after discharge, and continuing for three months,” Lee said.

Enhanced support also included the option to speak with a human counselor hired and trained by the research team each time participants were contacted.

All patients in the enhanced-treatment support cohort were enrolled automatically in the ongoing intervention, while only 25 percent of those assigned to the usual-care arm enrolled in the Quitline.

Furthermore, 84 percent of the enhanced treatment patients completed at least one counseling call, compared to 25 percent in usual-care cohort who did so.

Enhanced Support Helps

The study, funded by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, measured participants’ seven-day, biochemically verified abstinence from smoking at six months after discharge.

“Among patients in the usual-care group, about 10 percent of fast metabolizers were abstinent at the six-month follow-up,” Lee said. “Among slow metabolizers under usual care, we saw 25 percent were abstinent. That’s the disparity in quit rates that we typically see between fast and slow metabolizers.”

In contrast, 17 percent of fast metabolizers in the enhanced treatment support arm were abstinent at six months, effectively cutting the gap between fast and slow metabolizers in half.

In terms of what may have driven this improvement among fast metabolizers, the study found that use of a combination of nicotine patches and gum or lozenges was significantly higher among those receiving enhanced treatment support as compared to usual care.

“Because fast metabolizers break nicotine down more quickly, they need higher doses of nicotine replacement to curb withdrawal symptoms and craving,” Lee said. “This points to a potential clinical takeaway that we may need to more strongly emphasize optimal use of nicotine replacement therapy when treating fast metabolizers for smoking cessation.”

Smoking Genetics Matter Greatly

“Smoking has a strong genetic basis, with twin studies indicating that 44 percent to 75 percent of the variation in smoking initiation, maintenance and cessation is heritable,” the authors explained.

“It’s important for us to be able to take the genetics of smoking into account.”

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable death in the U.S, with 11.5 percent of U.S. adults currently smoking.

“It’s important for us to be able to take the genetics of smoking into account and understand differences in peoples’ ability to stop smoking based on their being fast versus slow metabolizers,” Lee said.

“Smoking cessation is still a major public health priority. We need to improve rates of smoking cessation.”