Patients who underwent elective surgery shortly after a COVID-19 infection fared far worse than patients whose procedures were scheduled farther out from the period of infection, according to new research published in JAMA Network Open.

In the study, Vanderbilt University Medical Center researchers examined outcomes for adults undergoing a variety of procedures in the weeks or months after developing the viral infection.

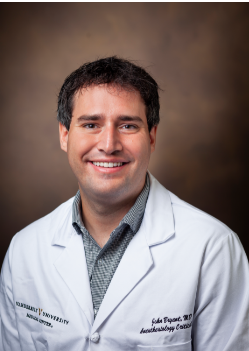

“We worked with a composite outcome that captured a wide variety of possible bad outcomes and found that patients who had surgery very early after a COVID infection had an almost 21 percent risk of major cardiovascular complications,” said co-author Robert Freundlich, M.D., an associate professor of anesthesiology and biomedical informatics at Vanderbilt.

“For patients who had surgery at 100 days after infection, the risk was cut in half, and it stayed flat between 100 and 400 days,” he said.

Factors in Timing

Scheduling surgery after COVID-19 infection is a common problem faced by surgeons and anesthesiologists, and it is only going to get more common over time, Freundlich explained.

“A recommendation had been offered, but it seemed to be an educated guess,” Freundlich said, of the American Society of Anesthesiology and the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation recommendation that procedures be delayed for four to 12 weeks.

“Patients and providers work together to choose the optimal date of surgery. This date is chosen for many reasons and, in many instances, patients have already taken time off from work and arranged for assistance recovering from surgery,” Freundlich said.

For many conditions, patients do worse if they wait too long to have surgery, he explained.

“These decisions are complex and need to be individualized to each patient and his or her reason for having surgery,” Freundlich said.

Broader Focus

The Vanderbilt study addressed the composite occurrence of deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, cerebrovascular accident, myocardial injury, acute kidney injury, or death within 30 days of surgery.

“We looked at specific bad things we think are related to COVID in some way, acknowledging that COVID is incredibly complex and impacts every organ,” Freundlich said.

Previous studies that addressed the question of surgical timing were considerably narrower in scope, he says.

“The earlier studies were generally small and only looked at cardiac patients or thoracic patients or neurosurgery patients or ob-gyn patients. And most of those studies looked at only one outcome, stroke or death, or kidney disease,” said co-author John Bryant, M.D., an assistant professor of anesthesiology at Vanderbilt.

“A stroke is bad, but so is kidney damage and heart damage and blood clots. Our study looked at everyone having surgery and all kinds of negative things that could happen,” Bryant said.

Large-Scale Analysis

For this retrospective cohort study, which was funded by the NIH and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the researchers analyzed the experiences of 3,997 adults who underwent surgery at Vanderbilt early in the pandemic, between January 1, 2020, and December 6, 2021. The patients’ median age was 51.3 years; 16.7 percent self-identified as Black, 74.8 percent as white, and 8.5 percent as another race.

The median time from COVID-19 diagnosis to surgery was 98 days. Approximately one-third of patients underwent surgery within seven weeks of their COVID-19 diagnosis.

Symptomatic or Not

Right after surgery, the risk of postoperative adverse outcomes was about 18 percent. By 100 days out, it reached about 10 percent, and it then kept declining steadily for the next 10 months, reaching approximately 8 percent after 400 days.

“Even if people didn’t have symptoms, they’d still benefit from a longer delay until surgery.”

The relationship between waiting longer after diagnosis to have surgery and reducing the risk of complications held true for both symptomatic and asymptomatic COVID-19 cases.

“We didn’t really expect to find out that even if people didn’t have symptoms, they’d still benefit from a longer delay until surgery. We think it has something to do with the virus causing inflammation, so the longer you wait, it’s potentially advantageous,” Bryant said.

Guides for Scheduling

“One of our big goals was to make a template for this kind of study,” Bryant said. And in fact, since the Vanderbilt team published their findings, he says several other groups have reported similar results.

“Our results provide clear indication that doctors and patients would do well to include proximity to COVID in their thinking.”

“The virus mutates, and there are new vaccines, so it’s useful for people to keep looking at this relationship,” Bryant said.

The authors acknowledge that in any individual patient’s case, many considerations can influence the best timing for surgery.

“Our results provide clear indication that doctors and patients would do well to include proximity to COVID in their thinking,” Freundlich said.