In 2017, the non-profit Enduring Hearts funded a pilot study at two medical centers to explore the utility of cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) parametric imaging in detecting biomarkers of heart transplant rejection in children.

The study leaders were Jonathan Soslow, M.D., director of the Pediatric Cardiac Imaging Research Center at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, and Lazaro Hernandez, M.D., medical director of the Pediatric and Congenital Cardiac MRI Program at Joe DiMaggio Children’s Hospital.

“This study was timely, since CMR advances over the past five to 10 years have improved our ability to detect myocardial inflammation and fibrosis,” Soslow said. “Our preliminary data demonstrated many CMR findings that are different in patients experiencing rejection compared to those who are not, indicating that we may be able to leverage CMR for diagnosis of acute rejection.”

Soslow and his colleagues are commencing a larger NIH study they hope will confirm their findings, as well as meet the broad goals of detecting rejection non-invasively and at a lower cost than with biopsy.

“We want to put patients through as few catheterizations with biopsies as possible,” Soslow said. “Adult studies suggest that CMR may be a safer, less costly method of detecting rejection. If this is also true in children, these tests could be done routinely, either to screen patients or at the time of clinical concerns.”

High Risks in Multiple Biopsies

Endomyocardial biopsy is still the gold standard for diagnosing rejection in both adult and pediatric heart transplantation. Tissue samples can reveal type of rejection and grade severity and enable evaluation of antibody-mediated versus acute cellular rejection.

“But biopsy is an invasive way to screen for rejection,” Soslow said. “Plus, it is limited, since samples are only taken from the myocardium on the right ventricular (RV) surface of the septum. Unfortunately, rejection can be patchy, and this can mean areas of rejection are missed by biopsy.”

He says patients may come in with all signs pointing toward acute graft rejection, but in about 10 percent of cases, the biopsies are negative. Additionally, biopsy frequency can become onerous for patients and the health care system. Some pediatric centers perform multiple surveillance biopsies, as many as 16 in the first year after transplant, and again every year or two thereafter, monitoring for signs of rejection.

“Each procedure is an expensive catheterization under anesthesia, with the attendant risks,” he said. “You could damage the tricuspid valve and trigger severe regurgitation, perforate the septum, and cause a ventricular septal defect or, theoretically, perforate the heart itself, leading to a pericardial effusion. The catheter can cause arrhythmias, and every biopsy creates some myocardial scarring.”

“CMR may be a safer, less costly method of detecting rejection.”

Enriched CMR Capabilities

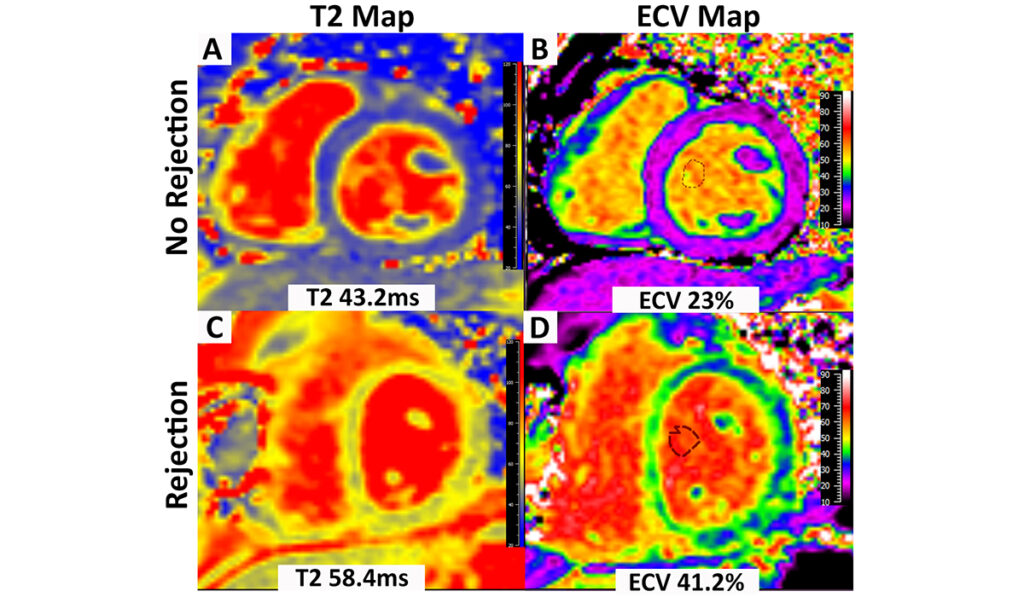

Today’s CMR may be an exciting alternative. Transverse relaxation time (T2) parametric mapping, in particular, provides information on inflammation-induced edema, a hallmark feature of rejection. Longitudinal relaxation time (T1) mapping, together with a hematocrit, can be used to calculate the extracellular volume (ECV), a sensitive marker of extracellular matrix expansion, which is indicative of edema or fibrosis.

CMR is also able to image the entire left ventricular free wall versus just the RV surface of the septum. Soslow expects that with continued improvements in sequences, resolution will allow more granular parametric mapping of the right ventricle as well.

Comparing Utility

In their pilot, Soslow and his team hypothesized that CMR results would discriminate between pediatric transplant patients with and without acute rejection. They performed biopsies and CMR on 30 patients, including 12 with rejection. The median age of study participants was 16 years.

They found that T2 and ECV were increased in patients with acute rejection, suggestive of edema and inflammation, and that myocardial strain was worse in patients with acute rejection, suggesting subclinical dysfunction. These findings held true for symptomatic patients with negative biopsies, Soslow noted.

“We might be able to eliminate 50 to 80 percent of biopsies and improve outcomes long-term.”

Biopsy as Confirmation

Repeat exposure to gadolinium contrast is a risk with CMR, but Soslow said that while ECV requires contrast, myocardial strain and T1 and T2 mapping do not.

“Our long-term goal is to evaluate whether we can do these MRIs without contrast,” he said. “If so, we can do them much more frequently, and quickly increase immunosuppression to mitigate long-term damage like fibrosis. Multiple rejection episodes put patients at a higher risk of chronic rejection or graft failure.”

Adult studies suggest that a combination of CMR and cell-free DNA from the transplanted heart circulating in the bloodstream might be an optimal way to screen for rejection, with biopsy still used for confirmation.

“We might be able to eliminate 50 to 80 percent of biopsies and improve outcomes long-term.”

Study Across 18 Sites

With a new NIH grant funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Soslow and his colleagues from Children’s Wisconsin and Carle Foundation Hospital will enroll patients from 18 different medical centers with excellence in CMR and pediatric heart transplant. Each patient will undergo CMR and blood testing, including cell-free DNA and micro RNA, at the same time as their scheduled cardiac catheterization with biopsy.

“The goal of this study is to confirm our findings and determine the best combination of tests to screen for acute rejection in pediatric patients” Soslow said.