Nearly half of individuals labeled as having beta-lactam allergies as children may be able to tolerate penicillin and cephalosporin as adults, according to new research from Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Without further investigation, this common allergy warning during the pediatric years could lead to a lifetime of prescriptions for second- and third-line antimicrobials when first-line treatments could be more appropriate. This raises both a patient’s risk of succumbing to antibiotic-resistant organisms and exacerbates the global drug-resistance problem, says Cosby Stone, M.D., a researcher in allergy and immunology at Vanderbilt.

“This research should give us a new sense of skepticism about these and other untested antibiotic allergies.”

Stone and Elizabeth Phillips, M.D., the John A. Oates Chair in Clinical Research at the Vanderbilt Drug Allergy Clinic, are two years into a prospective study of a screening tool that could be used to stratify patient risk through safe oral challenges, leading to removal from patient records of unfounded allergies.

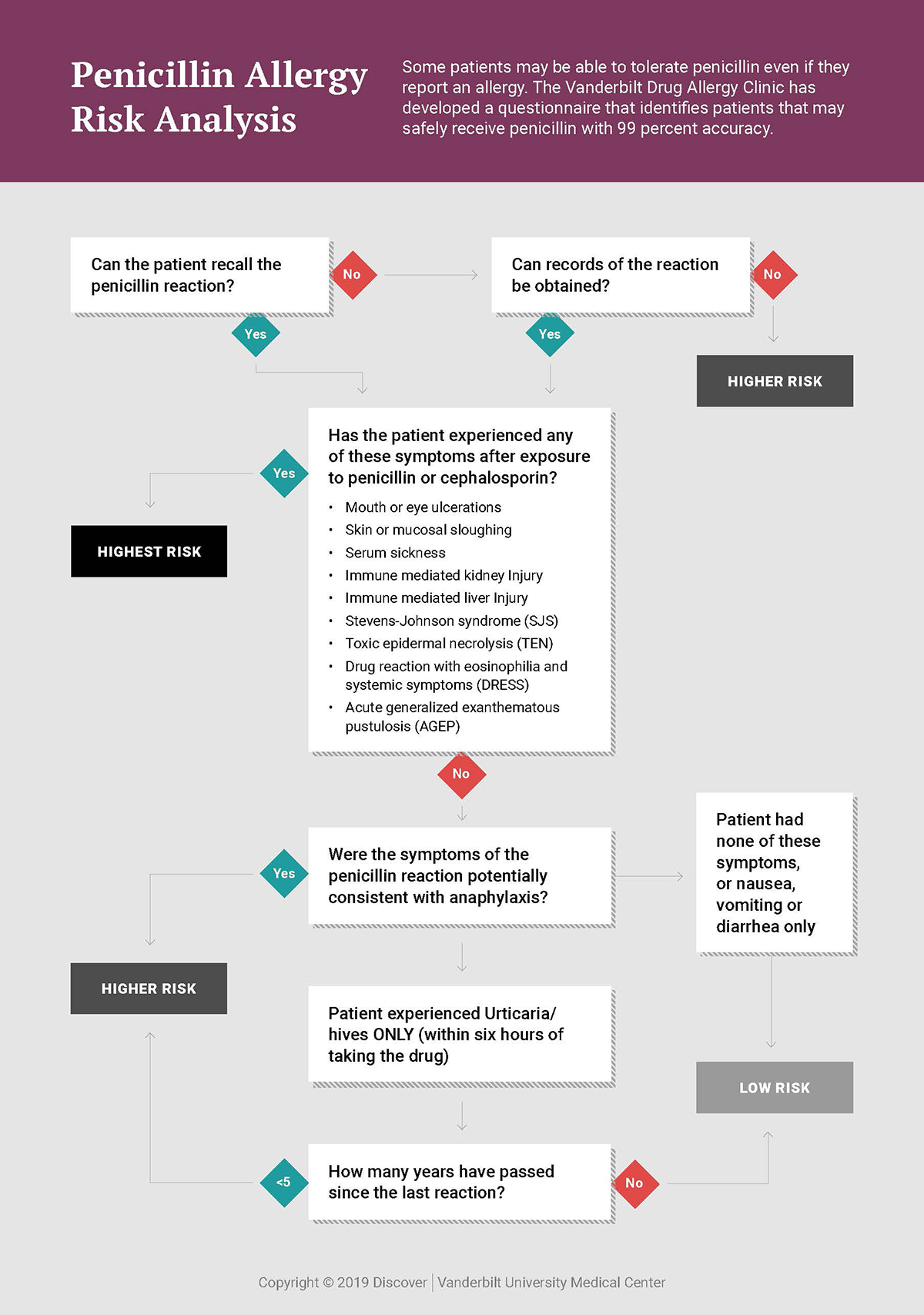

In an initial retrospective study, the risk stratification tool proved 99 percent accurate in identifying patients who were at low risk of presenting an allergic reaction to penicillin. This tool has since been used to guide the testing and removal of around 50 percent of penicillin allergies in ICU patients that were evaluated between March 2019 and March 2021.

“This is a problem that crosses national boundaries, with as many as 15 percent of patients in the U.S. estimated to have a penicillin allergy listed in their chart,” Stone said. “This research should give us a new sense of skepticism about these and other untested antibiotic allergies. It should also give us optimism that we can recognize most of the allergies that are risky just by talking to the patient.”

Risk Stratification Identifies Challenge Candidates

The team has integrated the tool into EPIC and made it easy for pharmacists to use.

“They take the list of patients flagged for penicillin allergy and ask each patient about their recollection of past allergic responses,” Stone said. “Using just four to five questions, they can quickly identify patients who can safely tolerate penicillin without requiring a skin test. We then offer them an oral challenge with amoxicillin as a way for everyone to clearly see it’s not an allergy.”

Patients qualifying as low risk typically reported experiencing minor, self-limited rashes, gastrointestinal distress, delayed onset urticaria, a remote history of immediate onset urticaria, or non-allergic type symptoms. Patients whose histories suggested a high-risk, delayed-type allergy and those with immune-system reactions such as anaphylaxis or organ injury, are excluded.

“If the patient turns out to have a low-risk penicillin allergy, they are offered the amoxicillin challenge,” Stone said. “For an hour we monitor them very closely and get extra vital signs, keeping epinephrine at the bedside, just in case.”

Patient response to the offer has been largely gratitude. “Eighty-five percent of the low-risk patients you approach about testing their allergy will say, ‘Yes, I’ll do that. That would be very helpful to me,’” he said.

Prospective Study Update

The first eight months of data from a prospective study of over 100 ICU patients showed that approximately 60 percent of those labeled with penicillin allergies are now considered low risk, Stone said. This mirrors the findings in the retrospective study.

“Since we began our program two years ago, more than 250 allergies have been removed from the records; and we’ve already seen more than 100 penicillin treatments given to patients who were cleared of their allergy label,” Stone said.

Stone said that none of the patients who met the testing criteria and who were honest about their original reactions suffered more than a mild rash as a result of the challenge.

“Only between 0.5 and one percent are going to have a rash, and this is in keeping with the average for antibiotic treatments at large.”

Benefits Run Broad and Deep

Penicillin is still the most common first-line antibiotic. It has a high tolerability, and because it is broad spectrum, it is less likely to select for drug-resistant organisms.

“Patients who avoid penicillin and cephalosporin have a higher risk of dying and are more likely to have an operative wound infection,” Stone said.

Particularly for immunocompromised patients, those who are transplant candidates, and those who have cancer and develop an infection, “penicillins and cephalosporins are drugs we want on the table,” Stone said. “They have fewer side effects than a second- or third- line drug like clindamycin or vancomycin, are more likely to kill the bacteria you are targeting, and less likely to select for drug-resistant organisms.”

Freeing more patients to take penicillin also helps fight the intensifying tide of drug resistance that drives methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Clostridioides difficile, and other intractable infections.

Expanding Efforts

Stone’s team is now rolling out the tool beyond the ICU, so far extending it across 12 internal medicine units. They anticipate that based on demand, that the pharmacy department will begin offering this service in other parts of the hospital soon.

Other allergies are on deck for scrutiny, Stone said. He is currently looking at data to see if cephalosporin allergies can be safely challenged without skin testing. He and Phillips are also considering further initiatives for challenging sulfa allergies, based on data from the Vanderbilt Drug Allergy Clinic. Removing outdated labels of sulfa allergy is especially important for immunocompromised patients.

“For these patients, there is no good substitute for weekly sulfa drugs to prevent infection,” Stone said.