The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) is again up for reauthorization in the U.S. Senate. As currently proposed, the updated bill includes additional funding and language shifts that aim to broaden its scope and better support families, rather than penalize them, through the creation of Family Care Plans.

In a recent New England Journal of Medicine perspective, Stephen Patrick, M.D., director of the Center for Child Health Policy at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, and colleagues offered an assessment of CAPTA’s current reach, with a focus on substance-exposed infants and their families.

“Imprecise terms are major obstacles to safe care. Properly identifying eligible families and infants in CAPTA is step one to receiving support.”

“The Senate reauthorization bill includes several key provisions that we believe are critically important in improving outcomes for families, perhaps the most important of which is allowing states flexibility to allow state public health agencies to take the lead in implementing Family Care Plans.” Patrick said. “In many states, it’s public health agencies that are best positioned to create these comprehensive plans given their reach to existing programs.”

Complex Eligibility

Patrick, who is also a neonatologist at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, notes there are challenges in recognizing infants currently covered by CAPTA.

To properly document a neonate with prenatal substance exposure, for example, hospitals must first notify child protective services. However, “substance exposure” is not represented in the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS), the data system used by states to track at-risk children.

Instead, state officials must cobble together available options such as “neglect” and “alcohol use – child” to create the designation. Additionally, current CAPTA language is vague, including the term infants “affected by” substances, which has no clinical meaning and leaves much room for interpretation, Patrick said.

“Imprecise terms are major obstacles to safe care,” Patrick said. “Properly identifying eligible families and infants in CAPTA is step one to receiving support.”

Preventing Unnecessary Foster Care

CAPTA support can be a critical prevention resource for many substance-exposed infants to remain out of the foster-care system and with their biological caregivers.

Recent work by Patrick and Sarah Loch, M.P.H., director of research operations for the Vanderbilt Center for Child Health Policy, further delved into this connection.

“Family Care Plans are intended to prevent foster-care placement, when possible, by connecting pregnant women to treatment and providing wraparound services to the family.”

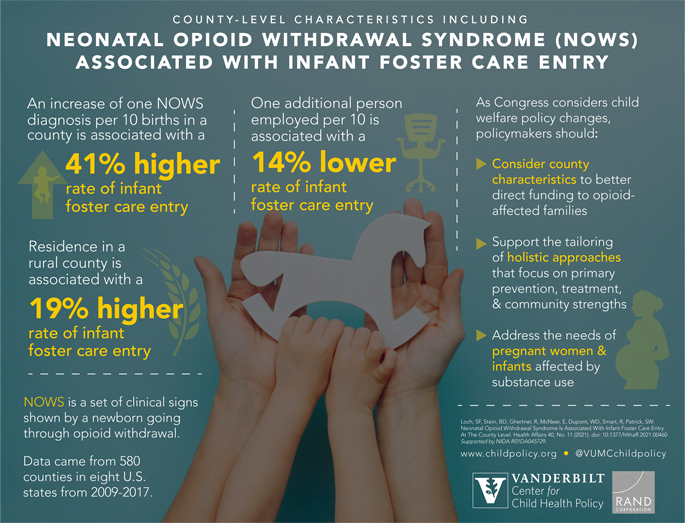

In an eight-year analysis published in Health Affairs, the researchers found neonatal opioid withdrawal diagnoses directly affect foster-care entry rates. Every diagnosis was associated with a 41 percent higher rate of foster-care entry across 580 counties. The researchers also found a 19 percent higher rate of foster-care entry in rural counties.

These kinds of county-level analyses should inform policy, Loch said.

“County characteristics can and should be considered by policymakers to better direct funding to aid opioid-affected families, who are at serious risk for foster care involvement,” she said. “In addition, our findings highlight the potential roles economic development and targeted, community-based support can play in this arena.”

Updated Language Broadens Support

Language updates to CAPTA may help officials better allocate services, the researchers said.

The Senate reauthorization bill makes a key swap from covering infants “affected by substance abuse or withdrawal symptoms, or a Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder” to those “affected by substance use disorder, including alcohol use disorder.”

While “affected by” remains in the bill’s language, the authors in their NEJM perspective write that “shifting from the use of infant diagnoses to the use of parental diagnoses focuses on the population in need of CAPTA’s wraparound services and connection to treatment.”

The reauthorization bill also softens punitive language while emphasizing the need for states to reexamine criminal justice approaches to substance use in pregnancy.

“If we want these policies to ultimately be effective, we have to give communities the flexibility to tailor responses in a way that makes sense for them.”

“Family Care Plans are intended to prevent foster-care placement, when possible, by connecting pregnant women to treatment and providing wraparound services to the family,” Patrick said.

Further Benefits, Questions Remain

To support implementation, the bill mandates creation of a separate CAPTA reporting system independent of the system to report child abuse and neglect. It also includes support for an interstate data-exchange system so agencies can better share information.

Still, without standardized clinical guidance – and intensive technical assistance – the researchers question whether new CAPTA benefits will translate to the local level.

“Federal child-welfare policy has been increasingly focused on prevention,” Loch said. “If you truly want to work with communities on this, you have to understand their unique strengths and needs. If we want these policies to ultimately be effective, we have to give communities the flexibility to tailor responses in a way that makes sense for them.”