Surgeons performing posterior cervical fusion (PCF) for conditions like myelopathy, radiculopathy or pseudoarthrosis enter the surgical suite with a distal point in mind for disk fusion – either the C7, T1 or T2 level. Yet evidence to guide this decision has been thin.

The missing element in past research has been scope and time. Previous studies categorized all fusion constructs as above or below the cervicothoracic junction (CTJ) and focused on short-term (one- or two-year) failure and revision rates. Now, a new study reports on longer-term outcomes with analysis of each individual vertebra around the CTJ.

Principal investigator Byron Stephens, M.D., division chief of the Orthopaedic Spine Program, and first author Joseph Labrum IV, M.D., chief resident in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, spearheaded the study. What they found provided clear guidance: fusions to T2 had negligible mechanical failure and revision rates and starkly contrasted with failure rates when stopping at C7 or T1.

“There’s been a debate about this for some time,” Stephens said. “I think we’ve been taught dogmatically by our mentors about the optimal lowest instrumented vertebra (LIV), without a lot of data to support those decisions. This study really gives us evidence to hang our hats on.”

Weighing LIV Risks

Most often, PCF surgeries are performed to relieve spinal cord compression. Multiple levels must be decompressed to open the canal, requiring a laminectomy across more than three levels, commonly extending down at least to C7. High construct stability and low segment stresses help avoid complications like pseudoarthrosis, fracture, hardware failure, junctional failure and adjacent segment disease and revision surgery.

“We believe this research could become a driving force in changing standard of care.”

Surgeons must weigh the risks, benefits and expenses in determining the LIV. More distal fusion means more stable constructs and lower risks of failure. It has been thought that stopping more proximally makes for a less invasive surgery and avoids stiffness, Stephens says, though it also increases the probability of revision surgery, with its associated expenses and morbidity. The new study probed the verity of these assumptions.

Multiple Superior Findings

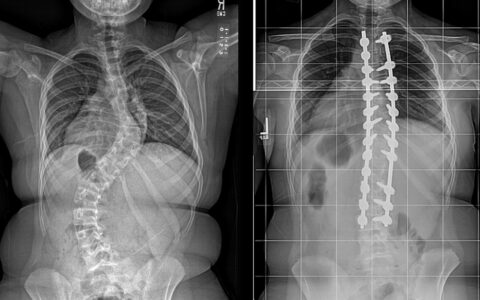

The investigators looked at 106 patients who had a posterior cervical arthrodesis (PCF) ending at C7, T1 or T2 to compare the progression of mechanical failure (ASD, hardware failure, fracture, junctional kyphosis and/or pseudoarthrosis) and revision surgery. Average follow-up intervals for the C7, T1 and T2 LIV cohorts were 36.3 months, 33.0 months and 29.7 months, respectively.

Findings showed:

- Mechanical failure rates for C7, T1 and T2 LIV were 30.6, 23.8 and zero percent, respectively.

- Revision rates for C7, T1 and T2 LIV were 25.0, 11.9 and zero percent, respectively.

- Average time to construct failure in the C7 and T1 LIV cohorts was 39.68 months and 29.85 months, respectively.

Contrary to the assumption that a distal extension to T2 risks increased morbidity, the study did not find this to be case. “We saw operative time and blood loss more related to the severity of spondylosis and deformity and the difficulty of decompression than to cervicothoracic LIV placement,” Stephens said. “Even the incision length was minimally different.”

“We believe that a PCF that stops at C7 is not addressing the unique biomechanics between the mobile cervical spine and the rigid thoracic spine,” Stephens added. “This is elevating the risks of adjacent segment stress concentration and mechanical failure.”

Lower Costs and More Data

“We believe this research could become a driving force in changing standard of care and could potentially result in decreased rates of adjacent segment disease and revision surgery for our spine patients,” Labrum said. “In addition to benefitting our patients, this may also benefit our health care system by mitigating the massive expenditures that are associated with revision spine surgery.”

Stephens, Labrum and their colleagues are now performing a meta-analysis, as well as a cost utility analysis to try to obtain a larger data set. “I think the most important thing we are doing is acknowledging that the time to revision is long – about 30 months,” Stephens said. “If you’re not following these patients out that long, you’re not going to see these differences we are studying.”