As capabilities in life-saving pediatric interventions rise, so do the risks of hospital-associated venous thromboembolism (HA-VTE). Determining individual risk and prophylactic intervention is often a murky clinical call. Guidance is sparse, since prior studies have focused only on adults or certain subpopulations, such as pediatric ICU or cancer patients.

Shannon Walker, M.D., a fellow in pediatric hematology and oncology at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, and her collaborators have tackled the challenge by designing and validating a model that predicts elevated risk across all pediatric populations in the hospital setting. This model is described in Pediatrics.

“These children can have chronic swelling and pain in that extremity that could last the rest of their lives.”

“We were trying to find a way to evaluate individual patients, first focusing on risk factors that have been determined to identify patients at higher risk of developing clots, and then targeting those patients specifically,” said Allison P. Wheeler, M.D. Wheeler is an associate professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, and principal co-investigator on a trial testing the predictive model. “We also wanted this model to have a personal touch, with hematologists helping clinicians make informed decisions on interventions,” she said.

Elevated Risk Among Children

Stasis, vessel wall injury and hypercoagulability are leading factors in blood clots. “Children are less likely to experience stasis, but more likely to have a proportionally large injury to their smaller blood vessels from a central line. Add in medications that may make them hypercoagulable, or other factors such as a cancer diagnosis, and you have a significantly elevated risk of a VTE,” Walker said.

Contributing factors to rising rates of pediatric HA-VTEs include more aggressive ICU procedures, such as catheters in ever-tinier blood vessels and the advent of procedures for very sick children that were inconceivable until recently. “We all celebrate the advancements enabling these kids to thrive, but they unfortunately increase the risk of VTEs,” Walker said.

“We also wanted this model to have a personal touch, with hematologists helping clinicians make informed decisions on interventions.”

Because HA-VTE is still rare in children overall, prophylactic anticoagulants are not considered standard of care as they are with adults, Walker says. “Because of the rarity, these risks may not be systematically considered, but those few who get blood clots can experience devastating consequences, from lifetime limb disability, to stroke, to death.”

Onerous Treatment and Sequela

Walker says that just having a blood clot typically means most young patients must have a minimum of six to 12 weeks of anticoagulation therapy, and as many as six months for pulmonary embolisms. “This may mean a little child has to get twice daily subcutaneous injections of anticoagulation medication for up to six months,” she said.

Another serious concern is post-thrombotic syndrome, where a clot damages the valves in these veins. “These children can have chronic swelling and pain in that extremity that could last the rest of their lives,” Walker said.

While work is underway at Vanderbilt to identify biomarkers associated with elevated VTE risk and treat children prophylactically, the researchers’ new model incorporates a range of clinical indicators that are obtained as part of routine care.

The Elevated Risk Model

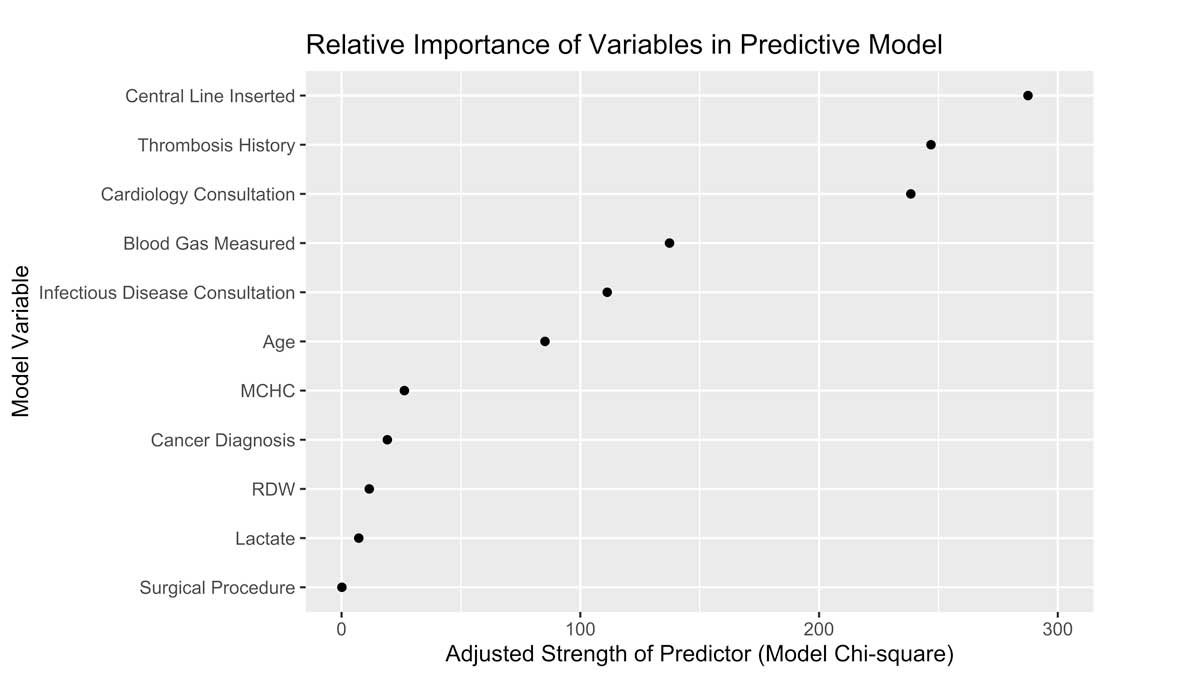

The researchers identified 40 factors potentially related to HA-VTE development among over 111,000 pediatric admissions, then winnowed these down to 11 of the most significant risk factors. The top three – central line catheterization, history of thrombosis and a cardiology consultation – represent a heavy proportion of these risks.

“We initially envision a hematologist receiving a risk alert, reviewing the patient record and then talking about options with the care team.”

Walker said some of the findings were surprising. “I expected that markers of inflammation or indicators for dehydration would rise to the top of the list,” she said. “Instead, we found other things, like elevated markers for red cell distribution, for instance, playing an important role. This has been shown to be significant in identifying patients at risk for severe COVID-19 cases and other infectious diseases. Now we are seeing the association with pediatric HA-VTE as well.”

EHR Flags and Interventions

The model was designed for automation within the EHR, flagging patients for review. “We initially envision a hematologist receiving a risk alert, reviewing the patient record and then talking about options with the care team,” Walker said. “We think about HA-VTE more often than most providers – this is a way we can share our knowledge with high-risk patients’ care teams automatically.”

In November, the team launched a prospective study – the Children’s Likelihood of Thrombosis (CLOT) trial – calculating VTE risk scores on every pediatric patient admitted to the Children’s Hospital. They are following these scores for half of the hospital on a daily basis, alerting providers to those children who may benefit from an intervention. They will then compare HA-VTE rates with those in the control half. All children continue to receive the current standard of care.

“We’re specifically testing the model to see if the alerts lead to preventative measures like use of anticoagulants, sequential compression devices or minimizing how long lines are in place,” Walker said.