In recent years, hip arthroscopy has evolved from a diagnostic procedure to an essential tool for tissue repair and minimally invasive treatment of hip dysplasia, femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), and other hip disorders affecting children, adolescents and young adults.

“Historically, hip problems were often left undiagnosed because they were poorly understood. We didn’t have good imaging studies, anatomic pathologies were missed on clinical evaluations, and athlete hip problems were oversimplified as ‘hip flexor strains,’” said Jaron Sullivan, M.D., an assistant professor of orthopaedics at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

“Historically, hip problems were often left undiagnosed because they were poorly understood.”

Vanderbilt is one of a handful of U.S. orthopaedic centers using hip arthroscopy as part of a comprehensive hip preservation program. On adolescent and young adult cases, Sullivan collaborates with Jonathan Schoenecker, M.D., a pediatric orthopaedic specialist at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, as well as Steven Engstrom, M.D., and Gregory Polkowski, M.D., both orthopaedic reconstructive surgeons at Vanderbilt.

Repairing Congenital Dysplasia

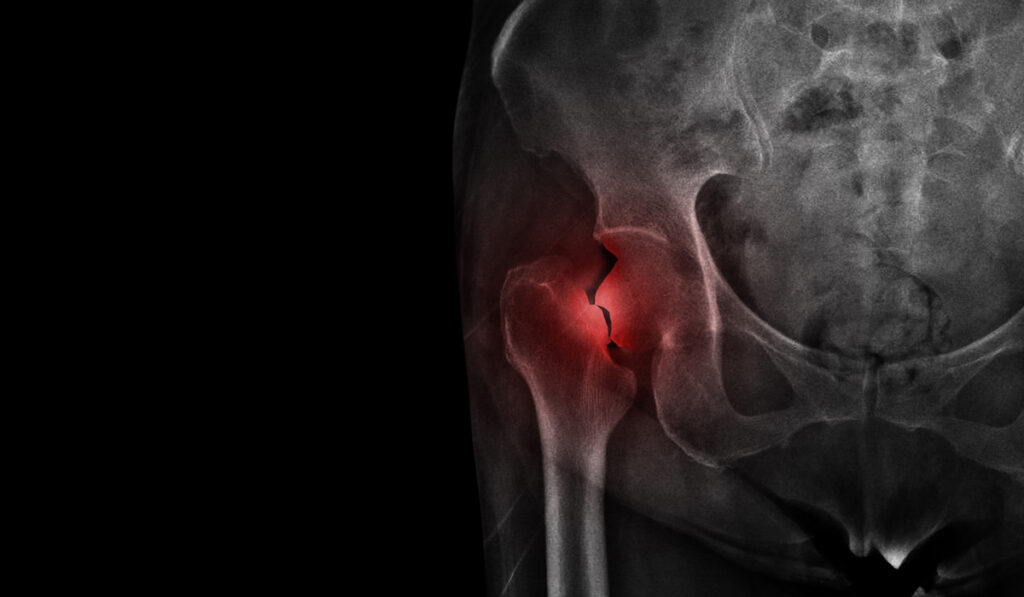

Sullivan explained that in congenital or developmental hip dysplasia, the instability can wear down cartilage or lead to an acetabular labral tear. The child may develop structural deformities or have pain in the groin or hip joint. Special views on plain radiographs and specific MRI protocols play a key role in determining whether children with hip dysplasia require salvage or reconstructive procedures.

“When a child’s hip doesn’t develop all the way and they have dysplasia, the socket is often not as deep as it needs to be. This causes a lot of wear and tear on the joint due to instability,” he said. “Early intervention is essential to ensure preservation of the hip joint.”

If the dysplasia is mild or borderline, Sullivan arthroscopically repairs the labrum and shaves down deformities of the hip that lead to degenerative osteoarthritis, which can help alleviate the child’s pain. In more advanced cases, Schoenecker may first perform an osteotomy to restore normal anatomy.

“Our goal is to create a hip that allows patients to enjoy a normal quality of life without limitations on activities,” Sullivan said.

“Our goal is to create a hip that allows patients to enjoy a normal quality of life without limitations on activities.”

Alleviating Hip Impingement

“Femoroacetabular impingement typically develops in patients as a result of stresses they place across the hip up until they reach skeletal maturity,” Sullivan said. He added that FAI precipitates symptoms that can surface in the patient’s 20s or 30s. FAI results in deformities on the cam (femoral) or pincer (socket) sides that increase contact pressure between the femoral head and the acetabulum. During activity – especially hip flexion movements – this can damage the articular cartilage or labrum.

Sullivan says that most adults who have degenerative osteoarthritis in their hip have these cam or pincer deformities. “Hip impingement is most common in people who are intensely athletic – they start getting groin pain that can take them out of sports participation. Treating these patients early improves their clinical outcomes scores at 10 to 15 years of follow up.”

FAI can usually be treated with arthroscopic hip surgery. “Orthopaedic surgeons used to just debride a labral tear – today, we try to repair it. If it’s not reparable, we recommend a labral reconstruction to restore normal anatomy and preserve function,” Sullivan said. Arthroscopy can also be used to repair another adolescent hip impingement, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, in which the growth plate slips and creates a deformity on the femur that juts into the socket, he noted.

Hip Preservation Research

In addition to clinical collaboration, the Vanderbilt hip preservation program includes a robust research enterprise. The program has been collecting outcomes scores on hip arthroscopies and is partnering with a larger research consortium to share the data.

“It’s very difficult to know the outcomes in a 20-year-old because you have to follow them for 30 years,” Sullivan noted. “However, it’s worth it if we can learn to preserve native anatomy and give people normal hip function throughout their life.”