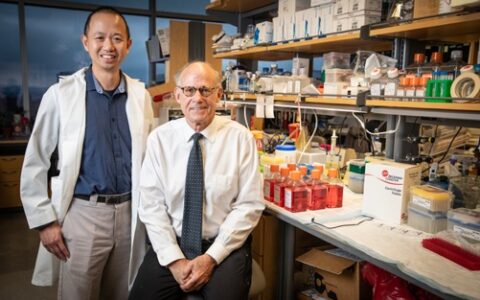

Research professor of medicine Martha Shrubsole, Ph.D., and colleagues at Vanderbilt University Medical Center have published the first study to evaluate intakes of meat, cooking methods and meat mutagens and risk of developing sessile serrated polyps (SSPs, also called sessile serrated lesions). Shrubsole previously reported that consuming high levels of red meat increased the risk of developing all types of polyps, but that the likelihood of developing SSPs was two times greater than the risk of developing adenomas and hyperplastic polyps (HP).

Conventional colorectal adenomas are the precursor lesions for most colorectal cancers. SSPs, however, represent an alternative pathway to carcinogenesis that may account for up to 35 percent of colorectal cancers. Because a diagnostic consensus for SSPs was not reached until 2010, few epidemiologic studies have evaluated risk factors.

Role of HCAs

Red and processed meat, classified by the World Health Organization as carcinogens, are risk factors for colorectal neoplasia. However, the mechanism is unclear. One possible explanation is the mutagenic activity of these foods during cooking through heterocyclic amine (HCA) intake.

The mutagenic activity of HCAs varies based on many factors including the method of cooking, cooking time, and temperature. HCAs become capable of damaging DNA when they are activated by specific enzymes in the body; the bioactivity of these enzymes may contribute to cancer risks associated with HCA exposure. One potential mechanism that could explain this process is the formation of DNA adducts, which increase with the intake of dietary HCAs.

Gauging Intake Preferences

The researchers used data from the Tennessee Colorectal Polyp Study, a colonoscopy-based, case-control study whose participants were recruited between 2002 and 2010 as part of the Vanderbilt GI SPORE. Telephone interviews were conducted during the original study to determine the participants’ medication use, family history and lifestyle factors.

Participants were asked about their usual intake in the past 12 months of 11 meats. For each meat, they were asked to report their usual intake frequency and serving size, the frequency of different cooking methods, and their preference for meat doneness level. Intakes of meat were converted to meat-derived mutagen levels based on the amount of meat intake and the usual level of meat well-doneness using the National Cancer Institute’s CHARRED software.

The intake levels were compared between cases with polyps (556 hyperplastic polyp, 1753 adenoma, and 208 SSP) and controls (3804). The highest quartile intakes of red meat, processed meat, well-done red meat, and the HCA 2-amino-3, 8-dimethylimidazo[4,5-f] quinoxaline were associated with increased risk of SSPs in comparison to the lowest quartile intake.

“The overall intakes of red and processed meats were slightly more strongly associated with SSP risk than well-done intakes of these meats, suggesting that it may not be well-doneness alone that is responsible for the increased risk,” said Shrubsole.

“The overall intakes of red and processed meats were slightly more strongly associated with SSP risk than well-done intakes of these meats.”

Moving Toward Prevention

Shrubsole said larger studies are needed to confirm that high intakes of red and processed meats are strongly associated with SSP risk, and that part of the association may be due to HCA intake. Future studies could also evaluate other mechanisms and the potential for primary prevention.

The authors concluded, “Meat intake and well-done meat intake are factors that can be modified in the diet; therefore, particularly for SSPs as well as other polyp types, strategies such as reducing red and processed meat intakes may be important for preventing [colorectal cancer].”