Bruce Compas, Ph.D., professor of psychology and human development at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, is an expert on resilience in the face of medical stress and adversity. Currently, Compas and his team are testing a novel online program aimed at reducing emotional distress in children with cancer and their families by teaching them evidence-based communication and coping skills.

The program is informed by decades of research. In a foundational longitudinal study, Compas and colleagues at Vanderbilt and Nationwide Children’s Hospital analyzed self-reports from over 300 children with cancer and their parents to assess how coping skills correlated with symptoms of anxiety and depression. The data informed the development of communication and coping guidelines for parents.

The new online program involves children in the training, which is a key strength, Compas said. “Most interventions that help families cope with the stress of a cancer diagnosis are focused exclusively on the parents. There has been less work to help children and adolescents develop skills that would be beneficial to them.”

Coping with Stress

Children have little opportunity to utilize primary control coping skills (e.g. addressing the illness through actions such as information gathering). Compas suggests clinicians should focus instead on helping children use secondary skills such as acceptance and cognitive reappraisal. This offers an adaptation to an uncontrollable stressor for the child and correlates to less anxiety and depression than the common response of disengagement coping (avoidance of thoughts and feelings).

Before cognitive reappraisal takes place, however, the child needs to feel understood. As part of their ongoing research, Compas and his colleagues asked participating families to complete questionnaires about coping and participate in discussions about the child’s cancer. They measured communication and adjustment one month, six months, and 12 months after the child’s diagnosis. “We thought that parents encouraging their child to use cognitive reappraisal would be most helpful,” Compas said. “However, parents first taking sufficient time to validate children’s feelings led to the best outcomes.”

Compas’ team has also found that mothers’ personal responses to cancer diagnosis can contribute to stressful outcomes. For example, maternal post-traumatic stress syndrome symptoms in the wake of a child’s cancer diagnosis may lead to less supportive communications with the child over time. “Parents may need to take the time to cope with their own distress first so they can most effectively help their children cope,” Compas said.

“Parents first taking sufficient time to validate children’s feelings led to the best outcomes.”

Online Coaching

Getting families to engage in coping and communication training early on can be difficult, Compas said. “Logic tells us to start communication and coping training soon after diagnosis since that’s when parents and children most need these skills. Paradoxically, that may be the hardest time for families to do it.”

To aid this, the team’s newly designed online communication and coping skills program aims to be as convenient as possible for families in the midst of a cancer crisis. Currently, the researchers are recruiting up to 150 children aged 10 and older and their parents to participate in eight sessions each, with support from trained coaches and homework to help the lessons stick.

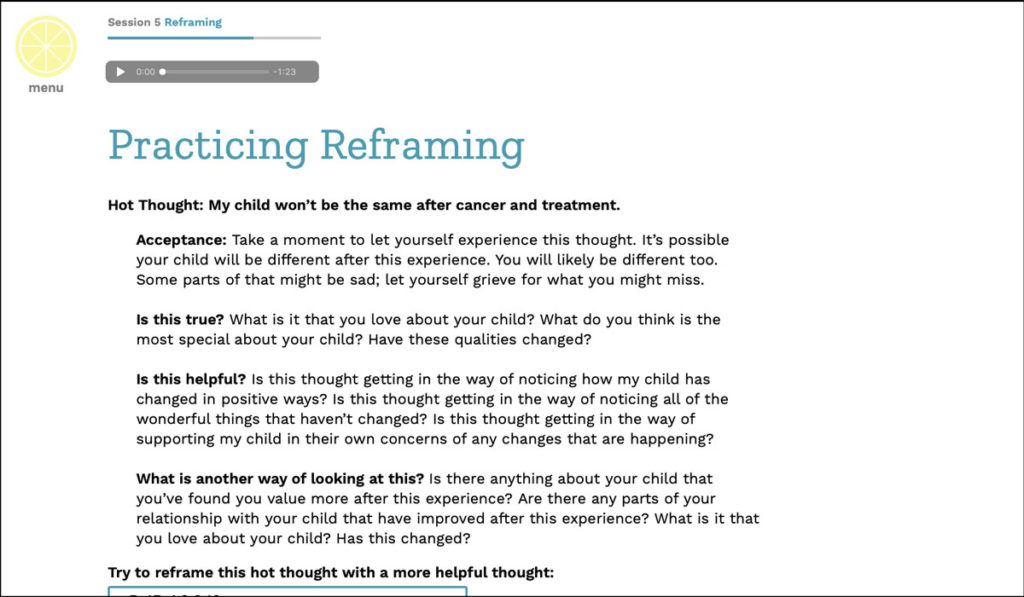

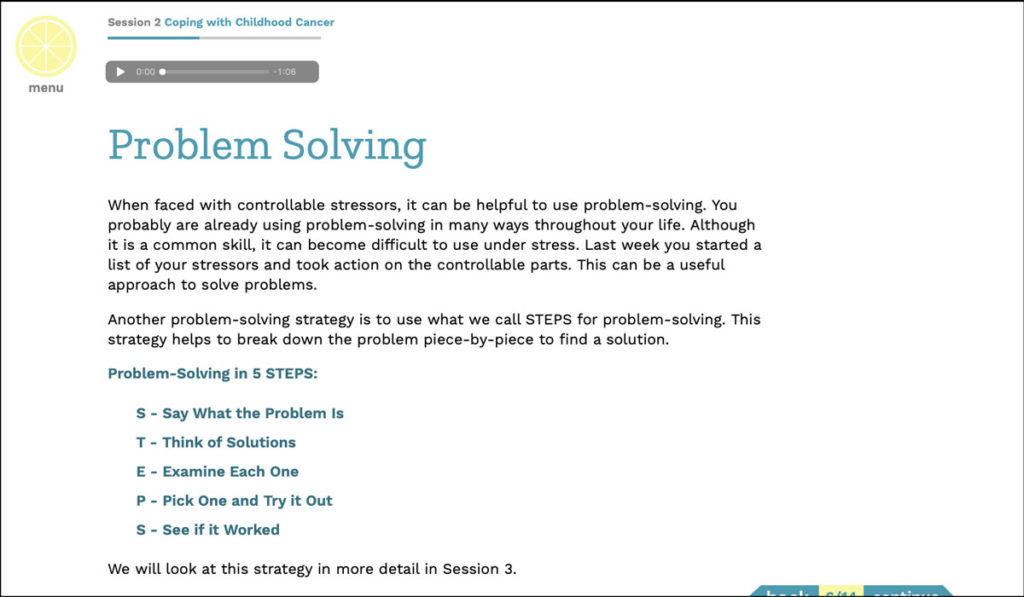

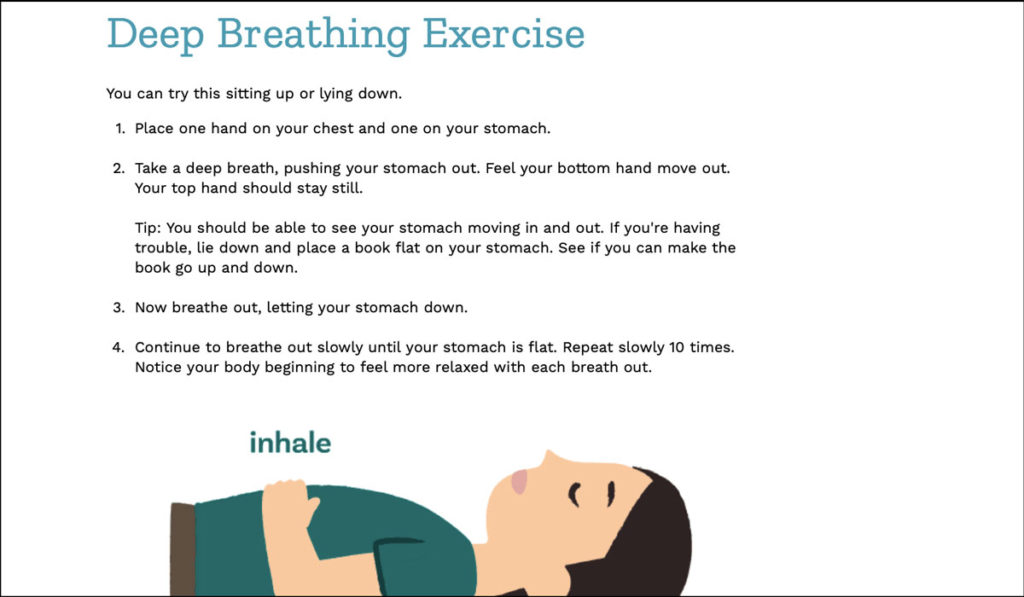

Parents and children log onto the program separately and are guided through sessions involving a presentation, examples to provide models of effective coping, and exercises for learning and practicing skills. After completion of each session, participants are encouraged to practice the skills through online “homework.” Training coaches provide feedback and encouragement online.

“Logic tells us to start communication and coping training soon after diagnosis, since that’s when parents and children most need these skills. Paradoxically, that may be the hardest time for families to do it.”

Refining the Program

In the future, sessions may be modified based on the age of the child, Compas said. “The way we’ll coach a parent of a five-year-old will probably be different from how we’ll coach a parent with a 15-year-old. We’re trying to evolve and tailor the program for parents of kids of all ages.”

The team will also vary the timing of the intervention to see if outcomes differ between training immediately after diagnosis versus six months later.