Teplizumab can delay the onset of clinical type 1 diabetes (T1D) an average of two years in children and adults at high risk, according to findings from TrialNet’s Teplizumab Prevention Study published last June in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The study’s findings led the FDA to grant Breakthrough Therapy Designation to teplizumab in an effort to expedite drug development and review.

“The key point for the millions of people at risk to develop this disease is we now have the first immunotherapy that significantly delays the onset of type 1 diabetes,” said William E. Russell, M.D., TrialNet principal investigator and director of the Ian M. Burr Division of Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Vanderbilt was the largest contributor to the study, enrolling more than 20 percent of the study participants. “We are now exploring a full-blown prevention trial in people even earlier in the disease process,” Russell said. “And also looking at delaying or preventing progression to stage 3.”

“The key point for the millions of people at risk to develop this disease is we now have the first immunotherapy that significantly delays the onset of type 1 diabetes.”

Teplizumab

Teplizumab is an anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody that modifies CD8 positive T cells, which are considered to be the main effectors of beta cell destruction.

While the drug has been shown to prolong insulin production in patients with new-onset T1D, the NEJM study was the first to report that teplizumab can delay disease onset in high-risk, prediabetic individuals.

Said Russell, “This is particularly good news for high-risk individuals in T1D families, as we know that the relatives of people with T1D are 15 times more likely to develop the disease than the general population.”

Delaying Diagnosis

Study participants for the phase 2 trial all had a relative with T1D, at least two diabetes-related autoantibodies, and abnormal results of an oral glucose tolerance test. Fifty-five of the 76 participants were 18 years of age or younger.

“The subject population all had measurable diabetes antibodies in their circulation, indicating that their immune systems were targeting their pancreatic beta cells,” Russell said. “Additionally, their glucose response to an oral glucose tolerance test was not normal, but it wasn’t yet in the diabetic range. We now call this stage 2 of type 1 diabetes.”

Participants were randomly assigned to either the treatment group, which received a 14-day course of teplizumab, or the control group, which received a placebo. All participants regularly received glucose tolerance tests until the study was completed, or until they developed clinical (stage 3) T1D.

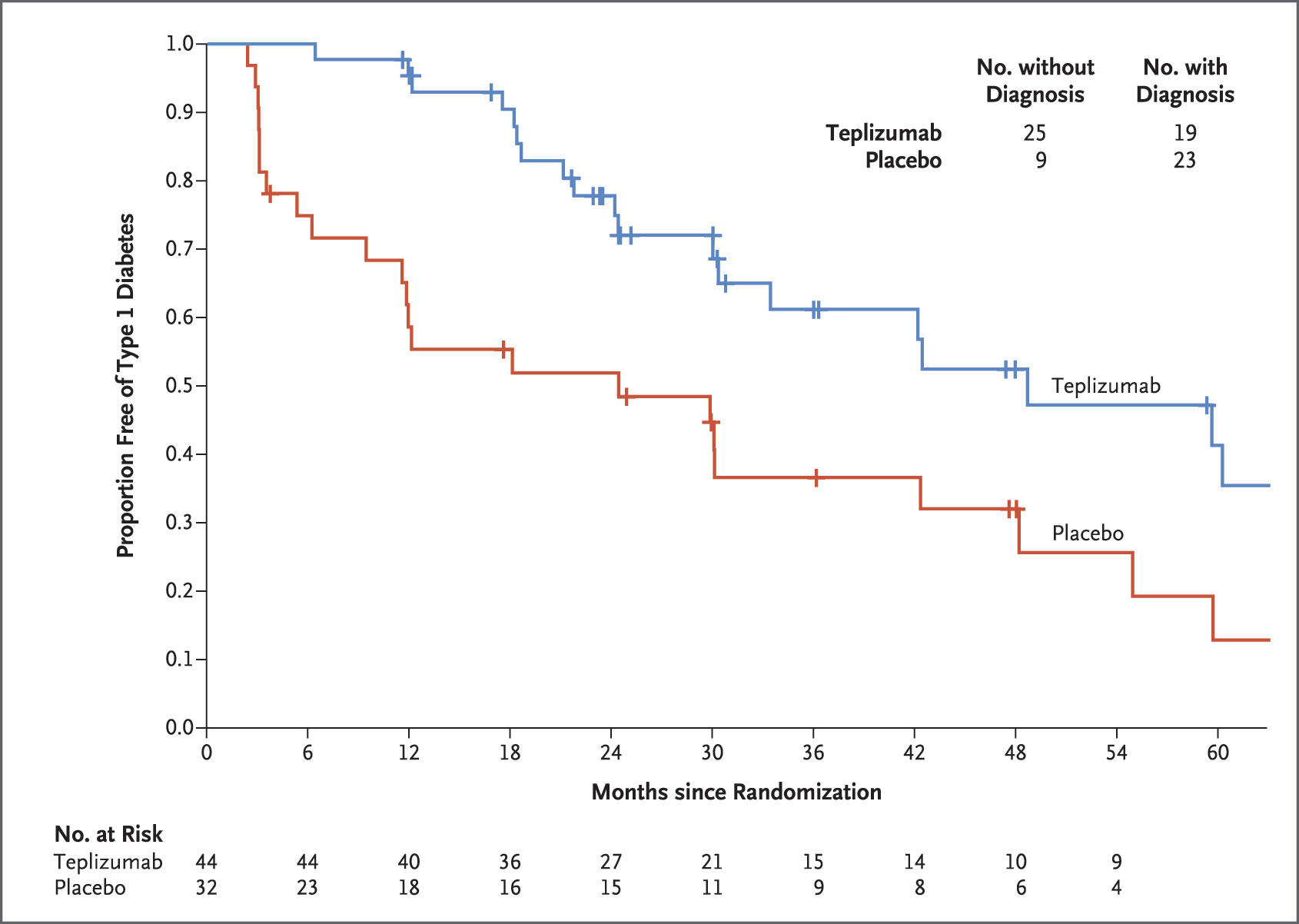

In the control group, 23 (72 percent) of the 32 participants developed T1D, compared to only 19 (43 percent) of the 44 participants in the teplizumab group. The median time to diagnosis was 24.4 months in the control group and 48.4 months in the teplizumab group.

“We’re beginning to refine our therapy to target the appropriate patient populations and also determine whether repeat treatments will prolong the beneficial effects of immunotherapy.”

Extending the Benefits

TrialNet researchers are currently conducting studies to look for ways to extend the benefits of teplizumab.

“We just began a new phase 3 study looking at the effectiveness of two rounds of teplizumab treatments, spaced six months apart, in preserving insulin secretion when started within six weeks of diagnosis,” Russell said. The prevention trial, which was conducted in both children and adults, showed greater efficacy in children, so the new study will be limited to those between the ages of eight and 17.

“We’re beginning to refine our therapy to target the appropriate patient populations and also determine whether repeat treatments will prolong the beneficial effects of immunotherapy on beta cell health,” Russell said. “It’s a very exciting era in the type 1 diabetes prevention space.”