Many in the media don’t wait for definitive studies before reporting that sports-related concussions (SRCs) are associated with neurodegenerative diseases. “The effect on the public can be more confusion, rather than helpful guidance,” said Scott Zuckerman, M.D., neurosurgery fellow and co-director for research at the Vanderbilt Sports Concussion Center.

Zuckerman believes healthcare practitioners specializing in concussion treatment have a dual responsibility to assure that SRCs are taken seriously and combat unduly alarmist reports. We caught up with Zuckerman on a six-month Global Health Neurosurgery fellowship in Tanzania and asked him to comment on news and reality related to sports-related concussion.

Discoveries: What information has been promulgated about SRCs that may be unfounded?

Zuckerman: First of all, sports-related concussions are a major public health concern and need to be taken seriously. Teaching athletes, parents, and coaches the signs and symptoms of concussion and to immediately remove the player when a concussion is diagnosed is vital to managing this ubiquitous injury.

However, many believe that the media has gotten ahead of the science in linking contact sport participation with neurodegenerative problems later in life. For example, one study that has gotten major attention over the last several years linked football participation before age 12 to neurocognitive problems in later life. At Vanderbilt, we performed a study of 45 retired NFL players and found no relationship between years of pre-high school football and neurocognitive problems.

Most of the long-term neurodegenerative problems we hear about are from studies targeting elite, professional athletes. These results should be cautiously extrapolated to the average Pee Wee or high school football player.

Discoveries: What did your recent chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) literature review reveal that might surprise many, even in the medical community?

Zuckerman: While the public may think concrete certainties exist regarding CTE and contact sport participation, there is a lot we don’t quite understand.

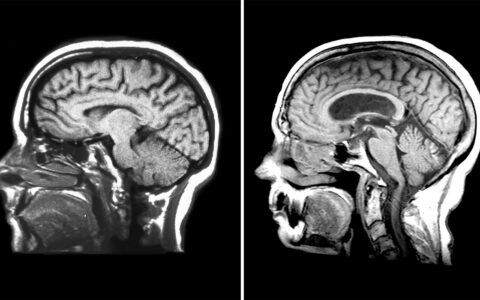

Many studies are not definitive because of selection bias, such as voluntary donation of brains, and less accurate ways of assessing symptoms and their onset, such as asking next of kin. The definition of CTE is also debated. Recent guidelines suggest only a single phosphorylated tau protein is needed to diagnose CTE, yet tau can be seen as a result of normal aging, chronic opioid use, epilepsy, and a host of other neurologic diagnoses. Confounding factors like narcotic use, alcohol use, and illicit performance-enhancing drugs can produce similar changes in the brain and are rarely accounted for.

“A true cause and effect relationship between chronic traumatic encephalopathy and concussions or exposure to contact sports has not been established.”

In all, there is a lot of association and not much causation established. This is the conclusion made by a panel of international experts in 2017 who stated that “A cause and effect relationship between CTE and concussions or exposure to contact sports has not been established.”

Discoveries: How can researchers gain more clarity on SRCs?

Zuckerman: We’ve advocated for more prospective studies that collect extensive histories on participants, without bias, over decades. These should include a wide enrollment that accounts for different sports with different head contact propensities, levels of participation and symptomology. Of course, this is a tall order, but given the far-reaching public health implications of contact sport participation and future neurologic problems, it is best to reserve judgment until we know more.

In fact, some studies similar to this have been conducted by the Mayo Clinic, and report no association between contact sport participation and neurodegenerative problems.

Discoveries: Looking at what we know today, are there other facts about SRCs that may have been distorted through the media?

Zuckerman: One common misconception is that a concussion is a bruise on the brain. But concussion is a functional injury, not a structural one. It’s a slowing of the brain processes, but usually, people recover fully in two to three weeks, or even faster, when the right protocol is followed.

Discoveries: What makes some athletes recover more quickly than others – is it more related to the severity or site of the impact?

Zuckerman: While those play a role, we’ve found that, on average, people who have migraines or psychiatric illness or even a first order relative with those disorders take longer to recover. People with learning ADHD are more prone to concussive injury to begin with and have also been shown to recover more slowly.

Discoveries: One of your articles notes that over 55 percent of high school students play contact sports. What is the takeaway for physicians who see these kids after they have failed the sideline tests?

Zuckerman: Each athlete is unique, with their own medical, social, and sport history, which underlies a mainstay of concussion treatment: that each injury should be treated with an individualized approach. A formal return to school and play protocol should be followed, within the context of “active recovery,” which includes slowly returning to normal life activities. Importantly, a return to learn always happens before any formal return to play.

Once the symptoms dissipate and the athlete is successfully returned to school and play, it’s natural for physicians, parents, and coaches to be on guard. But the positive impact that team sports can have on a young athlete’s life – the camaraderie, physical fitness, teamwork, personal growth, work ethic, unselfishness and integrity, should not be overlooked.

Discoveries: Dr. Zuckerman, thanks for speaking with us today.

Zuckerman: Thank you.