Following strong results from the 17-center SANTE trial, in April 2018 the FDA granted approval of Medtronic’s deep brain stimulation (DBS) device for patients with refractory, partial-onset epileptic seizures. Since 2002, DBS has demonstrated significant symptom reduction in movement disorders such as Parkinson’s and essential tremor. Now, with evidence of a 69 percent reduction in epileptic seizures after five years, 30 centers of excellence, including Vanderbilt University Medical Center, are beginning to provide this treatment for epilepsy.

A Minimally Invasive Answer

For approximately one-third of the 3.4 million Americans with epilepsy, medications do not relieve their severe and debilitating seizures. “It is exciting to have a better tool for helping these patients, whose lives are so compromised by this disorder. Many are unable to drive and in a state of constant anxiety over having another seizure,” said Dario Englot, M.D., an assistant professor of neurological surgery, radiological sciences and biomedical engineering, and the surgical director of epilepsy at Vanderbilt.

Until now, further treatment options for these patients, who have typically tried three, four, five or more different medicines, have been limited to invasive surgery.

While DBS placement involves surgery, it is considered minimally invasive. Electrode implantation is accomplished by making two 14mm holes in the skull, through which the surgeon places electrodes into the anterior thalamus. The surgeon then threads two leads from the electrodes down behind the ear, where they continue subcutaneously down the neck and attach to a pacemaker-sized pulse generator implanted just below the collarbone.

To mitigate risks associated with the procedure, only a select number of Level Four teams, as designated by the National Association of Epilepsy Centers, are performing it at this time.

Refining the Therapy

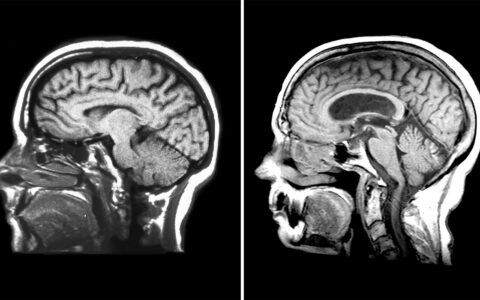

While electrode placement remains challenging, using a combination of functional and structural MRI raises the accuracy in identifying seizure-inducing nuclei, Englot notes.

Englot sees 3D volumetric reconstructions of the patients’ brains providing an even more granular view, enabling still more accurate electrode targeting. “Together with [Vanderbilt engineer] Benoit Dawant, our group is performing these reconstructions, assessing different variations on the treatment therapies and their outcomes, and registering these data to an atlas,” Englot said.

More research is also needed into optimal type of stimulation. “Right now it is a standard pulse,” Englot said, “but it may be improved through a feedback mechanism that results in stimulation only when the patient is likely to have a seizure.” Englot foresees using a closed loop sensing system that will incorporate recordings of brain activity, determine likelihood of having a seizure, and then selectively and preemptively stimulate nuclei to prevent seizures.

“We have ongoing research doing functional and structural MRI studies of the subcortical brain in people with epilepsy. These areas may not be where the seizure activity originates, but they communicate all over the brain, including to areas where seizures start and areas important for cognition,” Englot said. “We are working to determine how the brain is connected abnormally in epilepsy, which will hopefully lead us to new targets for electrode placement.”

Doing More for Patients with Epilepsy

“Our way forward in epilepsy is, number one, to stop the seizures, but number two, to treat the comprehensive problems that the patient is having.”

The SANTE study found that not only could DBS reduce seizure frequency in the short term, but it attenuated seizure activity over time. The number of seizures patients experienced declined over years of follow-up. Nearly one fifth of the patients had six months free of seizures, and six patients had two years of seizure-free life.

Yet many patients with epilepsy have executive function abnormalities in addition to suffering seizures. “Our way forward in epilepsy is, number one, to stop the seizures, but number two, to treat the comprehensive problems that the patient is having,” Englot said. “This includes their cognitive and behavioral problems.”

One pending question is whether putting patients through a long trial of multiple medications should be revisited. If two medications have failed, the likelihood of a third working is low. “Time is of the essence,” Englot said. “The more seizures you have, the more damage they cause to the brain, and the longer seizures go on, the harder it is to stop them.”