In this Discoveries interview, Michael Byrne, D.O., stem cell transplant physician with Vanderbilt University Medical Center, discusses factors that must be considered when determining the optimal timing of allogeneic hemopoietic cell transplant (HCT) in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).

Discoveries: You’ve written a forthcoming review article for Current Hematologic Malignancy Reports that highlights factors confounding decisions about allogeneic HCT. What motivated you?

Byrne: There is a growing understanding that our previous means of assessing disease risk for patients with MDS (using IPSS and IPSS-R* scores) exclude key variables that are important predictors of disease biology. In some cases these newer data may be discordant, so transplant teams rely heavily on the latest medical research, discussions with colleagues, and participation in shared decision-making with patients and their families. Collectively, our goal is to optimize the timing of allogeneic HCT, improve post-HCT outcomes, and maximize the life expectancies of these patients.

“These newer data may be discordant, so transplant teams rely heavily on the latest medical research, discussions with colleagues, and participation in shared decision-making with patients and their families.”

The overview that Nathalie Danielson, M.S.N., and I have written is an effort to define the challenges that clinicians face, including the current limitations in our understanding.

Discoveries: How would you describe the significance of the “transplant or wait” decision?

Byrne: When considering transplantation, we ask two questions: first, is the patient healthy enough for transplant? Second, is transplant appropriate for the patient’s disease biology at that point in time? To answer these questions, we consider the contributors to non-relapse mortality, such as frailty, organ dysfunction, and other predictors for death from transplant. Clinical and molecular features that predict for poor clinical outcomes may provide guidance in optimizing HCT timing.

Withholding potentially curative therapy in a life-threatening disease is often at odds with the patient’s and their family’s wishes and/or goals of care. In contrast, delivering this therapy also carries significant risks of morbidity and mortality from graft-versus-host-disease, infection, secondary malignancies, and other post-transplant complications, in addition to relapse of their underlying MDS. Before we agree to move forward with HCT, we want to ensure the potential benefits of transplant outweigh the risks for our patients.

Discoveries: What is some of the “key evidence” that might change the decision model?

Byrne: Next generation sequencing (NGS) is one of the more recent tools that has become available, but NGS data can be at odds with conventional scoring systems, or patients may have a combination of favorable- and poor-risk mutations, leading to uncertainty in decision-making. For example, when patients with low-risk disease by the IPSS or IPSS-R have poor-risk mutations by NGS, or when NGS panels report both favorable- and poor-risk mutations, providers may disagree over the optimal management.

Second, response to front-line therapy may be an important prognostic factor, yet this is absent from the IPSS and IPSS-R. Both scoring systems are based on disease characteristics at diagnosis and neither are validated to predict for post-transplant outcomes.

The complexity of these decisions, and pace of discovery in our field, give transplant physicians and disease experts the opportunity to work together, to remain fluid in our thinking of MDS disease biology, and to not become formulaic in our decision-making.

“NGS data can be at odds with conventional scoring systems, or patients may have a combination of favorable- and poor-risk mutations, leading to uncertainty in decision-making.”

Discoveries: What are the biggest challenges in developing a dynamic risk assessment instrument?

Byrne: As transplant becomes safer, it becomes harder to study outcomes in older datasets. Data from ten years ago may not accurately reflect the outcomes we see today, much less five or ten years from now.

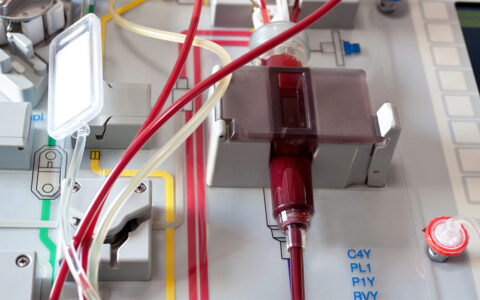

Collecting sufficient data is another challenge. At VUMC, we perform about 100 to 110 allogeneic transplants a year. While this is a large number for a moderately-sized center, after factoring in the heterogeneity of the patients, it’s not a large enough number to draw broad conclusions. Thus, we need to collaborate with other institutions or rely on transplant registries to answer certain research questions.

Discoveries: What do you see as the best approach to dealing with the current state of flux?

Byrne: We have to acknowledge that the state of flux is a reflection of modern medicine and is associated with exciting opportunities for further research. More data means the potential to make more informed, thoughtful decisions and personalize medical care, even if absorbing and integrating it is more complicated.

Discoveries: How is Vanderbilt contributing to a better understanding of the key variables?

Byrne: We are retrospectively studying our patient outcomes, both as a single institution and in collaboration with other centers. Efforts are underway to dovetail conventional clinical and molecular variables in MDS with NGS data at diagnosis.

We want to learn whether improvement, or upstaging by the conventional scoring systems, leads to better post-transplant outcomes. For example, if a patient has abnormal cytogenetics at diagnosis that clear with treatment prior to HCT, can we expect an improvement in their post-HCT outcomes?

We are also leading an effort to pool outcomes of patients with TP53 mutations, which are generally associated with poor clinical outcomes. We hypothesize that TP53 mutations are also associated with a higher risk of dying from transplant. With larger numbers from multiple centers, we hope to identify patterns of failure that will improve the supportive care for these patients, possibly including optimized timing of transplant.

*International Prognostic Scoring System; International Prognostic Scoring System – Revised