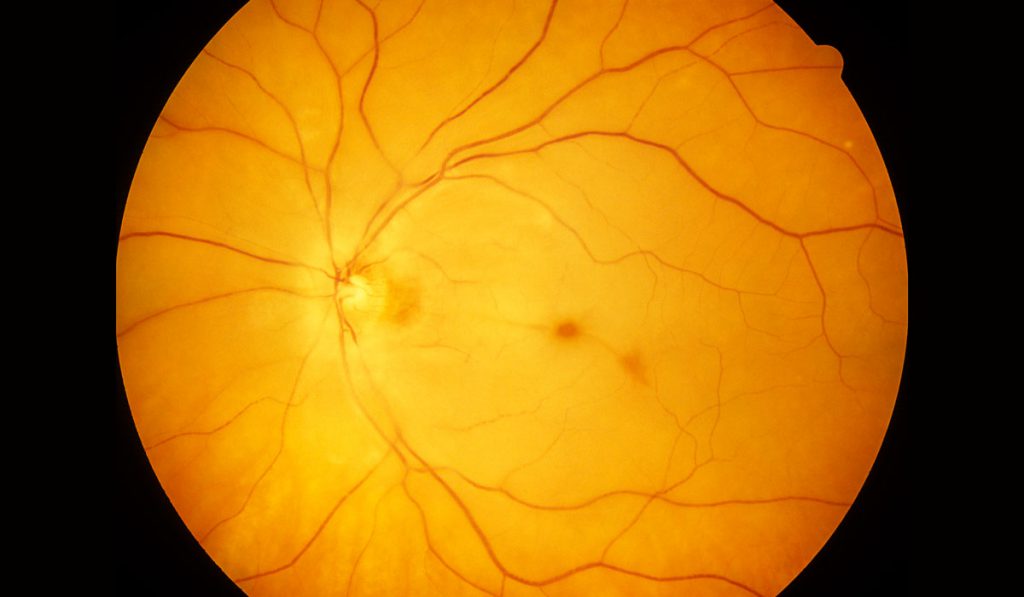

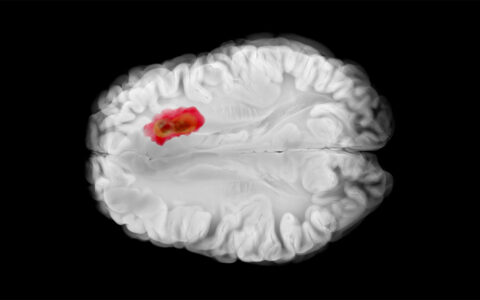

Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) — an ischemic injury to the retina that can result in permanent blindness — is similar to ischemic stroke in many ways. Whether it should be treated as equivalent to stroke in terms of risk factor screening has been a matter of controversy between neurologists and ophthalmologists.

A recent Vanderbilt University Medical Center study, published in the American Journal of Opthalmology, shows that patients with CRAO are at significant risk of future cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events and often have undiagnosed risk factors that may be modifiable.

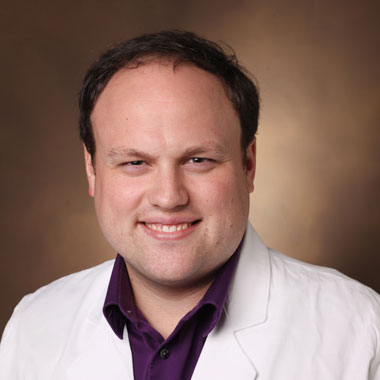

“Most neurologists see a CRAO as a very small stroke,” said Matthew Schrag, M.D., assistant professor of vascular neurology at Vanderbilt. “Traditionally it was as an ophthalmologic problem. When we conducted a poll of neurologists and ophthalmologists who treat patients with CRAO, we found significant variability in their approaches to screening and treatment.”

The CRAO Evaluation Protocol

For this reason, Schrag and colleagues at Vanderbilt sought to assess diagnostic effectiveness of the standardized stroke evaluation in patients with acute CRAO and to evaluate the rate of stroke, myocardial infarction and death in this population.

“We hoped to determine if patients with CRAO have risks as high as those with transient ischemic attack,” Schrag explained. “When we evaluated the severity of disease, it became obvious that these patients were very sick; they often had severe risk for stroke.”

Patrick Lavin, M.D., a neuro-ophthalmologist who helped lead the study, developed a protocol for CRAO evaluation implemented in 2009 at Vanderbilt. The protocol refers patients with acute CRAO to the general emergency department with co-management by vascular neurologists and ophthalmologists. The evaluation utilizes the recommended stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA) assessment with the addition of a detailed ophthalmologic examination and screening for arteritis.

A Retrospective Look at CRAO Patients

The Vanderbilt investigators used data from a 103-patient cohort with a confirmed CRAO diagnosis who were evaluated using the CRAO protocol between January 2009 and December 2017. Patients were included who had a diagnosis of CRAO with acute painless vision loss and visual acuity in the affected eye worse than 20/200, with confirmation by funduscopic examination and ancillary testing when necessary. These patients were admitted to the vascular neurology service for stroke evaluation consisting of angiography of the head and neck by CT or magnetic resonance angiography, brain MRI, echocardiography, cardiac telemetry and basic laboratory testing, including low-density lipoprotein, hemoglobin A1c fraction, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein level and complete blood count.

When no explanation for the CRAO was discovered, patients were asked to undergo long-term cardiac telemetry, usually for 30 days, to evaluate for atrial fibrillation. Any diagnosis, acute procedure, or change in medications made based on the inpatient admission was recorded. Clinical events in the following two years were recorded for those patients who obtained their long-term medical care at Vanderbilt or an affiliated institution.

CRAO as a “Stroke Equivalent”

“We’ve put so much value on protecting people’s vision with CRAO that we haven’t been screening for serious comorbid disease.”

The analysis was successful in identifying significant cerebrovascular risk factors in patients with CRAO that may be missed by incomplete screening strategies: 23 percent of patients had evidence of a serious systemic inflammatory reaction and 33 percent had a hypertensive crisis. MRI of the brain was obtained in 66 percent of patients and revealed a stroke in 37.3 percent—in many of those cases the area of ischemia was small and without an obvious clinical correlate.

“We’ve put so much value on protecting people’s vision with CRAO,” Schrag said, “that we haven’t been screening for serious comorbid disease. This challenges the status quo.”

Currently, a larger working group of institutions is being assembled to study the protocol. “Our hope is that as more and more studies are done and more and more voices are heard, the protocol will become standard practice,” Schrag said.