Relatives of patients with interstitial lung disease are at increased risk of developing familial pulmonary fibrosis, with interstitial lung abnormalities (ILAs) an early radiologic biomarker of the condition.

Questions have remained, however, about whether very mild ILAs hold the same implication for pulmonary risk as more advanced presentations.

Since 2008, a Vanderbilt University Medical Center team has led a longitudinal, prospective study of asymptomatic people who have at least two relatives, including a sibling or parent, with pulmonary fibrosis to look for early signs of abnormalities.

In a previous analysis of this cohort, there appeared to be a considerable length of time between the first incidence of radiologically detectable evidence of the disease and development of symptomatic pulmonary fibrosis.

The new interim analysis, published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, helps quantify the progression risk among relatives with CT abnormalities and to describe the characteristics of participants with new or progressive ILAs. National Jewish Health in Denver contributed to the analysis.

“The main goal of the study is to evaluate characteristics, particularly CT findings, that are associated with subclinical disease — abnormal changes on CT that are getting worse over time or the development of symptomatic pulmonary fibrosis in these at-risk individuals,” said Margaret Salisbury, M.D., assistant professor of medicine and first author of the study.

“Individuals with very early changes in the lungs that are detectable on CT but who have not yet developed symptoms comprise the ideal population for future clinical trials to identify treatments that prevent progression toward symptomatic familial pulmonary fibrosis.”

Longitudinal Follow-up

Participants in the study were enrolled at the Vanderbilt Lung Institute. From 2008-2023, 273 participants enrolled and then returned for at least one follow-up HRCT scan. Among these individuals, progression was defined by the identification of new or worse ILAs on a follow-up HRCT or the development of pulmonologist-diagnosed familial pulmonary fibrosis.

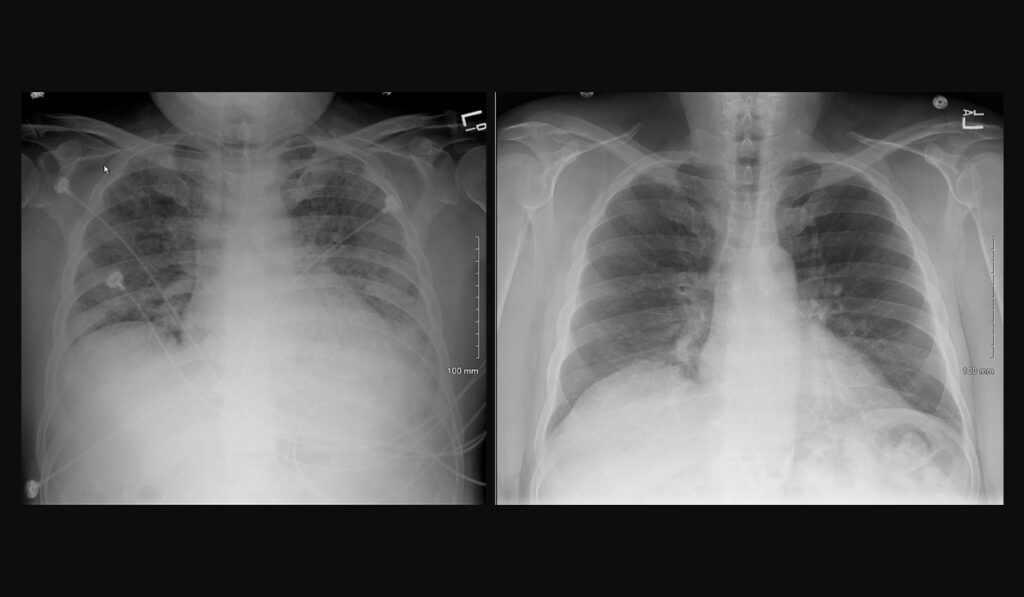

The investigators used the threshold for ILAs as described by the Fleischner Society to evaluate interstitial abnormalities on the enrollment HRCT scan. Patients were grouped based on whether they had ILAs in less than or more than 5 percent of a lung zone.

ILAs occupying 5 percent or less of a lung zone were sub-classified as mild. Moderate cases were those involving an area greater than 5 percent of a lung zone. The risk-to-experience progression was compared among those with mild or moderate ILAs to those with no interstitial abnormalities on their enrollment CT scans.

During a mean follow-up of 6.2±3.0 years, progression had occurred among 15 percent of those who presented no ILAs at enrollment. Progression was noted in 65 percent of cases labeled mild and among 77 percent of those with moderate ILAs.

The analysis determined that in persons at-risk for familial pulmonary fibrosis, minor interstitial abnormalities, including reticulation that is unilateral or involves less than 5 percent of a lung zone, frequently represent subclinical disease that is likely to progress over time.

“They had about nine times the risk of going on to progressive disease, compared to people who had no abnormalities at enrollment,” Salisbury said. “And people who had moderate ILAs had 17 times the odds of progression as those without ILAs.”

Taking the Trial Forward

Follow-up of this cohort will continue, Salisbury noted. “Blood relatives of those who have familial pulmonary fibrosis can join the study, even if they aren’t known to have pulmonary fibrosis.

People between the ages of 40 and 75 who have relatives with pulmonary fibrosis are eligible to come to Vanderbilt for study visits over a period of time, where they are screened for subclinical or asymptomatic early disease using HRCT, as well as pulmonary function tests and blood tests. An environmental history questionnaire is administered prior to the screening CT.

“We hope to get more information about the rate of disease development and progression as more people return and get their follow-up CT scans every five years.”

“We hope to get more information about the rate of disease development and progression as more people return and get their follow-up CT scans every five years. We’re also studying how environmental factors contribute to disease progression,” Salisbury said.

“The fact that a lot of people with early changes do progress suggests that even very minor findings on the CT scan might be meaningful and some of these environmental factors could be avoided.”

Adapted from an article by Nancy Humphrey in Vanderbilt News.