Results of the largest clinical trial ever performed in pediatric cardiology were recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine, addressing a longstanding question about use of preoperative steroids for open-heart surgery. Interestingly, however, it is also drawing attention for its unusual approach to running a large, pediatric clinical trial in an economical, efficient manner.

Called the Steroids to Reduce Systemic Inflammation After Infant Heart Surgery (STRESS) trial, the investigation showed that in less-complex surgeries prophylactic methylprednisolone helped, but in complex surgeries the steroids didn’t matter much.

“We found that whether or not steroids are used doesn’t make a huge difference when you consider all the infants involved. But there were significant differences in certain subgroups, particularly in the less severe cases,” said Scott Baldwin, M.D., co-director of the Pediatric Heart Institute at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt and an author on the study.

“I’d say that we recommend using steroids. You don’t have to do it, but it won’t hurt, and it may help.”

“We complain about lack of funding for large pediatrics trials. We can keep complaining or use approaches like this one to do quality research efficiently.”

A Common Problem

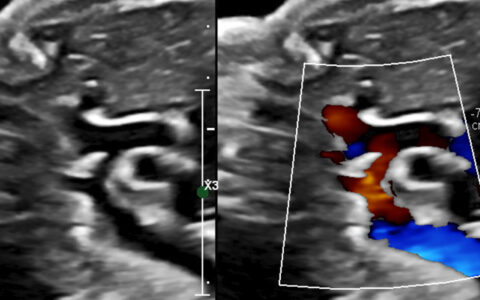

Congenital heart disease represents the most common genetic birth defect in the United States, diagnosed in utero or shortly after birth in one in 110 children – approximately 40,000 – each year.

Studies of steroid use to prevent inflammation during adult bypass surgeries have not shown much impact on outcomes, and prior pediatric studies of the issue have mostly been small and underpowered, Prince Kannankeril, M.D., a co-author of the paper and director of Vanderbilt’s Center for Pediatric Precision Medicine explained.

“People don’t know if steroids work or not in infants, although there’s been a theory that children might have a stronger response to steroids, and they would be more useful,” said Kannankeril. About half the centers that perform congenital heart surgery in the United States use steroids and half don’t, he added.

“The reason for that even split is that nobody had any data. Everybody just does what they’ve always done, not knowing for certain whether it helps or hurts,” Baldwin said.

“I’d say that we recommend using steroids. You don’t have to do it, but it won’t hurt, and it may help.”

Conclusive Answers from a Large Patient Pool

For the randomized, prospective, registry-based study, 1,200 infants undergoing heart surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass received either prophylactic methylprednisolone or placebo. The study was conducted across 24 sites.

The researchers used a scoring system which ranked possible outcomes from a high of 97 down to 1. The highest score, 97, indicated death, 96 indicated the need for a heart transplant, 95 indicated neurologic deficit, tracheostomy, or dialysis, and scores decreased successively as outcomes, including length of stay measures, grew more positive. Overall, compared to placebo, methylprednisolone did not reduce the likelihood of a “worse outcome,” the researchers found.

Steroid use was associated with a higher likelihood of hyperglycemia requiring insulin treatment. However, the odds of postoperative bleeding requiring a second surgery were reduced in the steroid group, and children who needed less-complex operations were more likely to benefit from the steroids.

“Everybody can do this kind of research if they want to.”

Working with Existing Data

While the findings were important, the research team’s design of a pragmatic clinical trial, one that evaluates the effectiveness of an intervention under actual practice conditions, using data from a registry is as significant as the findings themselves, Baldwin stressed. He believes this approach makes research accessible and affordable for diverse health care organizations that lack needed resources such as money and clinical expertise.

Using data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database, which captures over 90 percent of congenital heart surgeries in the United States, reduced expenses for the research team, in large part by eliminating the cost of enrolling pediatric patients, an expensive undertaking.

Baldwin noted that using preexisting data registries for research has been a staple feature of pediatric oncology trials for some time. “Every pediatric patient with cancer is enrolled in a clinical trial, and oncologists have been doing this for a while,” Baldwin said. “We are adopting their approach.”

Centers that perform congenital heart surgeries routinely enter all the data needed for this kind of study, and it is of high quality, says Baldwin, explaining that the Society for Thoracic Surgeons adjudicates the data.

“They make site visits twice yearly to ensure the data is true and accurate.”

Opening Up Research Opportunities

Using registry data allows many subspecialty pediatrics programs to take part in academic studies, including small departments and those in less research-oriented medical centers, Baldwin stressed.

“We complain about lack of funding for large pediatrics trials. We can keep complaining or use approaches like this one to do quality research efficiently,” Kannankeril said.

Baldwin agreed: “Everybody can do this kind of research if they want to.”