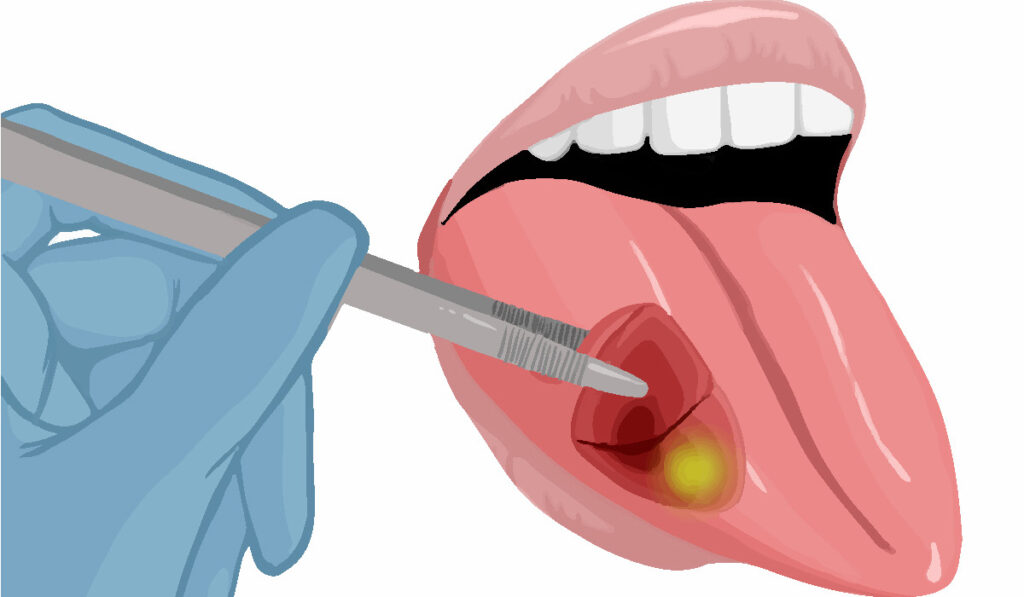

By adding fluorescent agents to molecules that target cancer cells intra-operatively, researchers have greatly improved the ability of surgeons to accurately remove malignancies.

“This technology makes cancer visible to the surgeon, so it becomes much easier to remove all the disease in a consistent way,” said Eben Rosenthal, M.D., professor and chair in the Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery.

“It is very challenging to see cancer. That is why the positive margin rate has not changed for most cancers over the past 20 years.”

Today, surgeons must rely on very subtle visual clues to identify cancer and also sometimes use their fingers to identify cancerous areas, which can feel firmer than healthy tissue. But these methods often have resulted in poor outcomes, Rosenthal explained.

“A large proportion of patients stand to benefit from this advancement.”

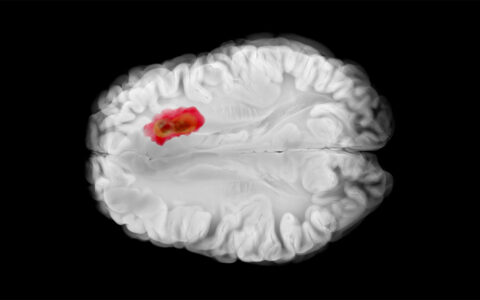

The method of employing fluorescent molecules intra-operatively already has FDA approval for use during surgery involving brain and ovarian cancers, Rosenthal said.

“We have published clinical trial data showing specific detection of pancreatic, brain, lung, skin, and head and neck cancers.”

It’s the Method, Not the Molecule

Work on this technique began in the late 1990s with the fluorescence being added to a molecule 5-aminolevulinic acid, now well established as a therapeutic agent for neurological and other cancers.

“It is very challenging to see cancer. That is why the positive margin rate has not changed for most cancers over the past 20 years.”

In a review of progress in the field in The Lancet Oncology, Rosenthal and coauthors described an expansion of similar agents, including indocyanine green, which is analogous to 5-aminolevulinic acid. In recent years, trials have begun with fluorescent agents demonstrating better molecular specificity and image contrast than earlier agents.

Rosenthal did not set out to create a new molecule for imaging, although his work led to panitumumab-IRDye800CW, a fluorescently labelled antibody useful for intraoperative tumor-specific imaging.

“I took an existing therapeutic with a known safety profile and added the fluorescent agent,” he said.

“Rather than saying this molecule is the one that is the best, we are saying, ‘If you use certain fluorescence-guided surgery techniques, it will provide patient benefit,’” Rosenthal said. “That is our goal, to show people the successful application of fluorescence-guided surgery, not to highlight a particular agent.”

“Within the next five years, fluorescence-guided, intra-operative surgery will be routine practice.”

Small Companies Taking the Lead

Several companies are involved in clinical trials for development of the new diagnostic, including On Target Laboratories and Alume Biosciences, which received loans from the U.S. Small Business Innovation Research program.

“Rather than saying this molecule is the one that is the best, we are saying, ‘If you use certain fluorescence-guided surgery techniques, it will provide patient benefit.’”

Rosenthal said research centered on diagnostics are not as lucrative as those for therapeutics, which have seen greater interest from large pharmaceutical companies.

“A patient will only get one dose of the diagnostic, compared to getting months of treatment of a therapeutic drug,” Rosenthal said.

Although the cost for trials and production are the same for treatments and diagnostics, a pharma corporation is far less likely to recoup its costs with a new diagnostic.

Immense Applicability

Almost every patient with curable cancer gets surgery at some point in their treatment, so a large proportion of patients stand to benefit from this advancement, Rosenthal said.

“This method offers potential benefits for patients that are so high,” he explained. “Within the next five years, fluorescence-guided, intra-operative surgery will be routine practice.”