A rotator cuff injury is the most common underlying condition noted when patients report shoulder pain.

Treatment options for most atraumatic injuries include surgery, physical therapy, or a combination of the two, but which treatments are most effective, and for whom, is still controversial.

Jed Kuhn, M.D., an orthopaedic research leader at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and president of the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons, founded the VUMC-led MOON (Multi-Center Orthopaedic Outcome Network) Shoulder Group in 2004. Since 2015, he and orthopaedic surgery department chair and principal investigator Rick W. Wright, M.D., have led a rolling entry study of patients with full-thickness tears treated with physical therapy, reporting on outcomes as data accrued.

Now, they have published their 10-year outcomes collected from 16 surgeons at 12 sites around the country to provide better clarity for orthopaedic surgeons in deciding whether and when to operate, prescribe physical therapy (PT), or recommend both.

“Historically, we were taught that all rotator-cuff tears needed surgery, but this research consisted of a collection of case studies from individual surgeons. That is not the greatest evidence to help decide the best treatments,” Kuhn said. “This study is a large prospective cohort where patients did physical therapy, and we looked to see what features led to failure of therapy and to surgery as a result. This information can help physicians determine who might need surgery and who might not.”

Degenerative Injuries

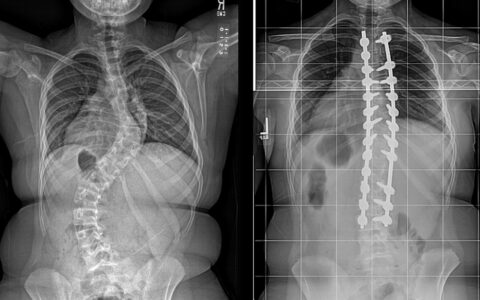

Kuhn says an atraumatic rotator cuff tear is more aptly envisioned as a degeneration rather than an actual rip in the muscle tissue.

“The likelihood of developing an atraumatic partial or full-thickness tear increases with age, affecting roughly 30 percent of people over the age of 60, 40 percent over 70 years old, and 50 percent over 80 years old,” Kuhn said.

He explains that while about 22.6 million Americans have rotator-cuff tears, most are unaware of it and never seek treatment. Fewer than 5 percent ever require surgery. This benign response can continue despite progression in the tear.

“Research shows that in about 48 percent of people who have a rotator-cuff tear, the tear will get larger over time,” Kuhn said. “For most people, the tear will progress so slowly that that the surrounding muscles compensate, and the patient experiences little pain or difficulty.

“In some cases, however, risk factors like a family history, diabetes, and smoking may cause more rapid progression, exceeding the patient’s ability to compensate. This can produce symptoms and may lead to a visit to the doctor.”

He noted that the speed of the degeneration is likely the biggest factor driving patients to surgery.

Nature, With a Nudge

While surgery is called for in some cases, most patients derive the greatest benefit from an optimized physical therapy program.

The MOON Shoulder Group enrollees with atraumatic yet symptomatic full thickness rotator-cuff tears have undergone physical therapy to determine their future need for surgery. A surgery option was available to patients at any time PT was deemed not effective.

Data reported in an earlier publication showed that 75 percent of patients who had physical therapy for atraumatic full-thickness tears avoided surgery throughout the two-year follow-up period, suggesting that physical therapy was highly effective in the short term at treating a patient’s symptoms.

In the group’s latest publication, the MOON team gave a 10-year report on 355 patients who had received treatment of their rotator-cuff tears with physical therapy.

At 10 years, 68 percent of these patients still had never undergone surgery. Among those who had surgery, 57 percent did so within six months of enrollment in the study, and 43 percent had surgery in the interval, between six months and 10 years.

Power of Believing

Of those who had surgery earliest, the patient’s expectations regarding the effectiveness of physical therapy was pivotal in their decision to have surgery.

“Essentially, if a patient believed therapy would work, it would work,” Kuhn said. “If the patient did not believe therapy would work, they had surgery. The decision to have surgery had nothing to do with the anatomy of the rotator cuff, the size of tears, or the level of a patient’s pain.”

For those who had surgery after the initial six-month period, other factors came into play, such as their worker’s compensation status or daily activity level, the researchers found.

“If someone experiences weakness or functional problems, that might be a better reason to have surgery,” Kuhn said.

Kuhn notes that newer advances – like platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy that may promote healing with platelet growth factors – also have been generally proving helpful in rotator cuff tears that have been surgically repaired. Stem cells are perhaps the most alluring therapy on the horizon

“At this time the jury is out on whether stem cells can be helpful or not,” Kuhn said. “We don’t yet know how to engineer them to build tendon or muscle, but if we figure that out, this will offer a very exciting new means of promoting healing.”