Researchers looking at inflammation factors in kidney injuries have found comparable issues in mouse models of obesity, discovering that adipose tissue macrophages (ATMs) are capable of both decreasing and increasing inflammation.

The research from Vanderbilt University Medical Center also showed that epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) can play a role in obesity and insulin resistance.

Raymond C. Harris, Jr., M.D., who holds the Ann and Roscoe R. Robinson Chair in Nephrology, and Ming-Zhi Zhang, M.D., a professor of medicine, collaborated on the three studies, which were published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation and Nature Communications (two papers, one on EGFR and obesity and one on EGFR and kidney fibrosis).

Cytokine Connections

Low-level chronic inflammation associated with obesity and adipose tissue can lead to metabolic syndrome, including insulin resistance, previous research has shown.

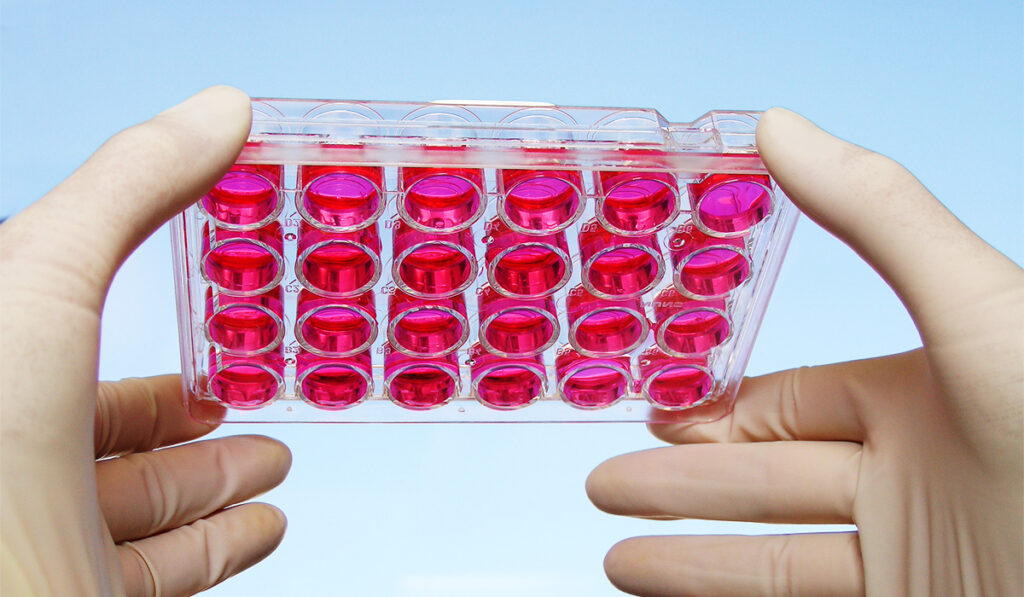

Adipose tissue macrophages are a source of cytokines that increase inflammation and worsen dysfunction in fatty tissue. But macrophages also express the cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) enzyme and the associated prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which can block pro-inflammatory cytokine release. Researchers explored whether this anti-inflammatory pathway in macrophages could ameliorate obesity’s effects on health.

The team had previously observed the inflammation-macrophage connection in studying kidney injury.

“We found that blocking the EP4 receptor [related to PGE2] in the macrophage had the effect of making acute kidney injury worse,” Harris said.

This led them to look at other inflammatory states, such as the type 2 model of diabetic kidney injury. In mice fed a high-fat diet to induce glucose intolerance and weight gain, they examined macrophages in fatty tissue, the production of prostaglandins, and the effect on signaling pathways.

Role of EGFR

Their investigations also focused on EGFR activation, which induces pro-inflammatory macrophage phenotypes. The team found that a high-fat diet increases expression of EGFR and its ligand, amphiregulin, in ATMs.

They also found that blocking EGFR activation decreases the amount of glucose intolerance, weight gain, and adipose tissue development in the mice. Similarly, EGFR expression increased in kidney fibrosis, and although it is not a causal link, a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms may point the way to therapeutic strategies to counteract inflammation and scarring, for which there is no specific treatment.

“It’s like yin and yang,” Harris said. “Knocking out the EP4 receptors made the macrophages more pro-inflammatory. Knocking out the EGF receptors in the macrophages actually prevented the inflammatory phenotype.

“In the mice where we deleted COX-2 so that PGE2 was not being made, adding an EP4 agonist decreased the amount of fat and the amount of inflammation in the fat, proving that this was a specific effect on the macrophage.”

Harris and Zhang are also examining the implications of the research for type 2 diabetes. Although any human pharmacological applications remain hypothetical, these studies have helped describe and illuminate the processes involved.

Some cancer drugs, such as erlotinib, block EGFR activation, but may bring side effects such as skin rash and diarrhea. EP4 agonists, used in one of the studies to decrease inflammation must be administered by implanted pump and are not available orally. Future developments could increase the practical uses of these substances, the researchers said.