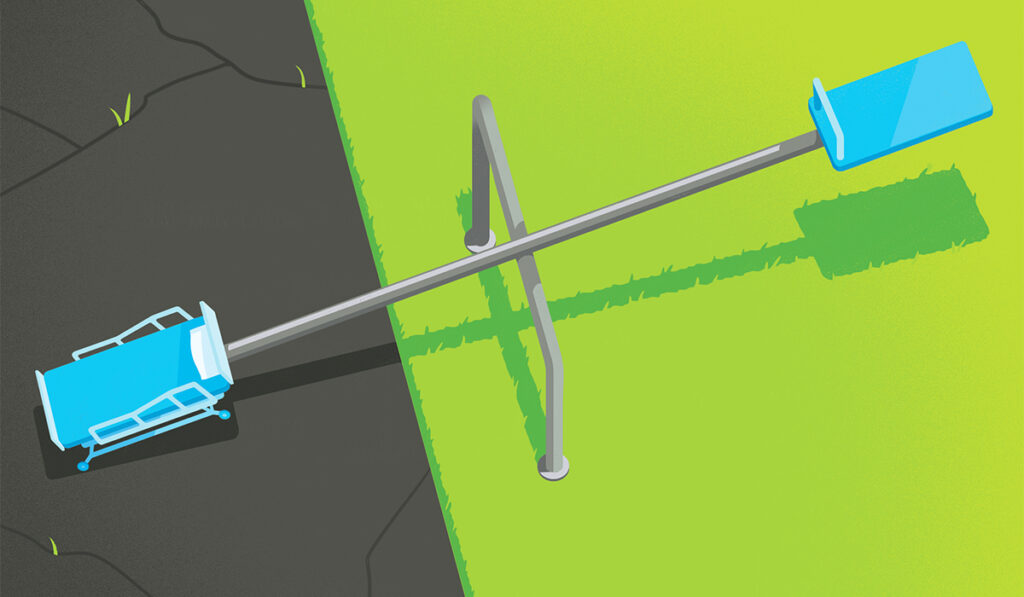

If a child lives with a supportive family in a safe neighborhood with good parks and schools among stably employed adults, their risk of hospitalization is half that of another child who lives in an area lacking such advantages, a new study finds.

“It matters where kids grow up. If they’re in a neighborhood with resources such as green space, healthy food, supportive family, lack of violence and racism, they do better overall and need inpatient care far less often.”

“It matters where kids grow up. If they’re in a neighborhood with resources such as green space, healthy food, supportive family, lack of violence and racism, they do better overall and need inpatient care far less often,” said first author Alison Carroll, M.D., an assistant professor of pediatrics at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt.

If children in areas of low opportunity and few resources were provided the same assets as those in the highest opportunity areas, an estimated 65,706 hospitalizations could be avoided annually, the team concluded.

A National View

“Some earlier studies, done in Cincinnati and Kansas City, looked at the association between a global measure that captures the quality of a child’s neighborhood and pediatric hospitalization rates, but our work looked at the association on a national level,” Carroll said.

“We know that social determinants of health are one of the most powerful predictors of health and health outcomes for children and adults, and we realized that we needed to better understand and measure them in kids.”

Because social determinants encompass so many aspects of a person’s life, it’s been hard to pin them down with a single measure.

Enter the Child Opportunity Index (COI). The index, created by Brandeis University researchers who are also co-authors of the study, provides a single measure for social determinants of health for each census-tract or ZIP code area by combining 29 specific indicators, divided into three main categories.

29 Measures Included

In the “education” category, for instance, the index measures access to quality early childhood education, the experience of elementary school teachers, and the education levels of adults. In “health and environment,” the index measures things like walkability, housing vacancy rates and levels of industrial pollutants.

In the third category, “social and economic factors,” it measures adult employment rates, home ownership and single-family households, among other characteristics.

Researchers have tried using household income or wealth as proxy measure, Carroll said, but that approach is limited.

“Globally it may be true that wealth matters, but we are also interested in other aspects than income that influence outcomes, things like not having polluted air or not having mold in the home that can directly impact an illness like asthma,” Carroll said.

Admissions Per Condition Analyzed

Carroll and colleagues applied the COI to better understand pediatric hospitalization rates in the United States. Their study used data from 18 states in the 2017 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project State Inpatient Databases (SID). The SID is an all-payer administrative database that includes inpatient records from all hospital stays in 49 U.S. states.

The study cohort included 614,823 hospitalizations among a total population of 29,244,065 children resulting in a hospitalization rate of 21 hospitalizations per 1,000 children.

A subset of diagnosis groups were examined after being identified as the most common and costly reasons for children to be hospitalized: (1) asthma; (2) respiratory infectious diseases including pneumonia or bronchiolitis; (3) non-respiratory infectious diseases such as cellulitis, urinary tract infections or gastroenteritis; (4) mood disorders; (5) sickle cell disease with crisis; (6) appendicitis; and (7) diabetic ketoacidosis.

Advantages Confer Benefits

As they used the COI to rank the opportunity level of each neighborhood, the researchers noted a striking association.

“As neighborhood opportunity goes down, hospitalization rates go up. It tracks.”

“As the opportunity level got higher, in areas with better education and more green space, the hospitalization rates declined. As neighborhood opportunity goes down, hospitalization rates go up. It tracks,” Carroll said.

“When we compared kids living in very low-opportunity areas with those in very high-opportunity areas, it was about a 1.8 times difference.”

The researchers also analyzed admission rates for the seven conditions individually.

“For each of the conditions, we found a similar pattern as we’d found for hospitalizations overall. Rates decreased as the COI increased,” Carroll said.

“The most striking differences were seen among children with asthma and sickle cell disease.”

Potential Applications

Individual providers can use the COI to understand a child’s environment, and as a risk stratifying tool, Carroll explained.

“We can use it to identify families and patients we ought to talk with some more, to learn about specific needs they may have which we can help address as they transition from the hospital back home,” she said.

Health care systems also play a role in policies that determine the nature of children’s neighborhoods. “We can use this data to understand where needs exist and are the most urgent.”

Carroll acknowledged the difficulties involved: “There’s not a lot of investment in caring for children’s health. It’s constantly an uphill battle.”

Carroll presented the findings at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting in 2023.