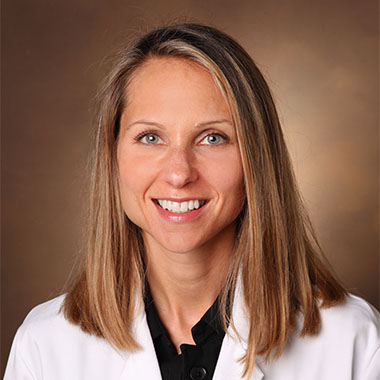

Revised treatment protocols are transforming the ways patients and physicians approach differentiated thyroid cancer, which represents 95 percent of all thyroid cancers, according to Lindsay Bischoff, M.D., an associate professor of medicine and medical director of the Vanderbilt Thyroid Center at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

In the past, treatment for differentiated thyroid cancer, which includes papillary and follicular thyroid cancers, nearly always involved total thyroidectomy, but increasingly patients with lower-risk forms of the disease are being considered for less aggressive tactics.

“Half the population have thyroid nodules, and 95 percent of those nodules are benign,” Bischoff said. “The majority of the remaining 5 percent that are thyroid cancer are nearly always indolent, not aggressive and not life threatening.”

With a low level of mortality for most, medical treatment will not be a life-saving intervention, he said, adding “we want to shift our focus to treating the patient and not the disease. We don’t want to perform unnecessary surgery or treatment. For these patients, we have found that less-aggressive measures typically have the same outcomes for them, with less risk.”

These cases may more appropriately be addressed with a partial lobectomy rather than complete removal. Another option is active surveillance.

“If a sub-centimeter nodule is found, even a suspicious looking one, it is usually not biopsied but instead followed up with ultrasound to watch for growth,” Bischoff said. “For that patient, the intervention would be worse than the thyroid cancer.”

“We want to shift our focus to treating the patient and not the disease.”

Guidelines Overhaul

Bischoff, who is serving as vice chair of the guidelines committee for thyroid carcinoma at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, is helping to update the recommendations.

“Updating guidelines is a huge undertaking, both as a medical thought-process and in terms of logistics,” she said.

In this case, active surveillance is a recent addition to treatment.

“This refers to biopsy-proven thyroid cancer of 1 centimeter or less that we don’t treat with surgery but instead follow,” Bischoff said.

Data from Kuma Hospital in Japan and from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center have significantly increased confidence for those using this guideline. It has even become less common to biopsy nodules of that size, with some researchers and clinicians recommending the limit be pushed to 1.5 centimeters, Bischoff said.

While most thyroid cancers are very slow growing, Bischoff noted the importance of an informed decision.

“It’s important that active surveillance is chosen in a shared-decision process between physicians and patients, and at a medical center that is able to follow up appropriately. The patient should be comfortable with the decision.”

Radioactive Iodine Changes

Under previous protocols, most all thyroid cancer patients would have the gland removed and radioactive iodine as treatment.

“And everyone went on lifelong thyroid hormone therapy,” Bischoff said. “We now know that low-risk patients don’t benefit from that.”

Differentiated thyroid carcinoma can, in a relatively small number of cases, be aggressive and cause significant morbidity, although mortality is rare, Bischoff says. The level of risk is ultimately determined by surgical pathology. But for presumed low-risk patients, partial thyroidectomy is favored over total thyroidectomy, offering similar outcomes with a lower complication rate. RAI also has been scaled back for the low-risk group.

Bischoff cites a noninferiority study involving RAI in thyroidectomy patients in which rates of thyroid cancer recurrence were similar between patients who did and did not receive the radioiodine.

“Now we can confidently say that low-risk patients should not have RAI therapy,” said Bischoff.

Similarly, serum thyrotropin (TSH) suppression therapy was not found beneficial for low-risk patients whose TSH is within the normal range.

Targeted Therapies

Patients with advanced disease may require chemotherapy intervention, primarily tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) used when a cancer is fast-growing or presents a mortality risk.

TKIs can be non-specific, such as lenvatinib, but some are targeted at driver mutations in the cancer. The most common is BRAF V600E, which Bischoff notes is also present in several other types of cancer. The pharmaceutical industry has developed several BRAF inhibitor drugs, such as dabrafenib and vemurafenib.

Molecular testing is another area in which guidelines have changed with more actionable mutations identified, including ALK fusion, NTRK, BRAF, and RET gene fusion.

“This type of testing is not used for all patients; it is used to make decisions about additional systemic therapy options for certain patients,” Bischoff said.

More frequently, molecular testing follows an initial biopsy with an ambiguous result as whether it’s cancerous or benign, she said.