Maternal-fetal medicine specialist Soha S. Patel, M.D., and her colleagues at Vanderbilt University Medical Center recently handled the successful delivery at 30-weeks’ gestation of a baby diagnosed with a nearly 4-cm umbilical vein aneurysm.

As described in the journal Case Reports in Obstectrics and Gynocology, the patient was healthy and thriving at six months.Such cases are particularly noteworthy in the field of maternal-fetal medicine due to the absence of randomized controlled trials. The lack of study data makes it tough to navigate a rare condition like fetal umbilical cord aneurysm, representing about 4 percent of umbilical cord abnormalities, which leaves specialists with only case reports to inform the more nuanced decisions.

While umbilical cord aneurysms are rare, some case reports indicate that they are associated with a fetal death rate of 4 to 5 percent, many times higher than the 0.6 percent overall fetal mortality rate in the United States. One review of 23 cases found a 35-percent incidence of comorbid major congenital anomalies, including multiple-anomaly syndromes and severe cardiac defects.

“Many umbilical cord abnormalities can be diagnosed as early as in the second trimester, but that does not mean we deliver every patient that early,” Patel said. “We wanted to use this case study as a means of describing what risks umbilical vein aneurysms pose, and how we decided on the course of action we took.”

Case Study of Concern

In the Vanderbilt case, a woman, 38, was transferred from a regional hospital with findings of severe fetal growth restriction, reaching only the third percentile, and reversed end-diastolic flow noted in the umbilical artery.

“With the size of this umbilical vein aneurysm, we knew we were facing the risk of clotting, compression or rupture.”

The Vanderbilt care team included Patel, along with an expert maternal-fetal medicine sonographer, a neonatologist and a genetic counselor.

The mother, who presented at 30-weeks, three-days gestation, had a prior history of a cesarean delivery and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Prior to transfer, she received two doses of betamethasone for fetal lung maturity and a magnesium sulfate infusion for fetal neuroprotection. The mother did not have abnormal blood pressure or lab abnormalities before delivery. Aneuploidy was ruled out, despite an increased risk of trisomy 21 on her first-trimester screening.

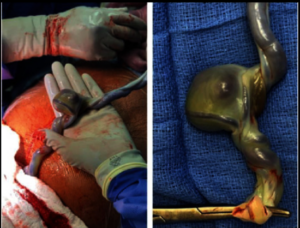

On ultrasound, the team identified a large free-floating umbilical cord aneurysm with non-pulsatile, turbulent flow that was disrupting blood perfusion to the placenta, with intermittently reversing end-diastolic flow in the umbilical artery and elevated flow through the ductus venosus.

“With the size of this umbilical vein aneurysm, we knew we were facing the risk of clotting, compression that would potentially compromise the blood flow or rupture, with uterine contractions only increasing this risk,” Patel said.

Arterial Distress

Given these considerations and the decreased fetal growth rate, delivery was recommended and the mother underwent a cesarean section the day after admission. She was postoperatively diagnosed with HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count) syndrome, started on magnesium sulfate for seizure prophylaxis, and discharged on postoperative day three.

Her son was 1,320 grams at birth, with APGAR scores of six at one minute and seven at five minutes. The team used stimulation and continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) to resuscitate the infant. He was admitted to the NICU, where he received a platelet transfusion.

Initial chest X-rays showed decreased lung volumes, diffuse granularity, and air bronchograms, mostly consistent with respiratory distress syndrome. He required intubation and mechanical ventilation for a day, and a single dose of surfactant. After extubation, he remained on nasal CPAP until 34-weeks’ gestation, followed by low flow nasal cannula until 37-weeks’ gestation, consistent with mild bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

The infant was discharged 67 days after his birth. Upon six-month follow-up, he was breathing without support and meeting developmental milestones.

From Diagnosis to Decision

When examining similar sonographic findings in an outpatient clinic setting, Patel said she would start by closely examining the umbilical cord and its sites of insertion. If an umbilical vein aneurysm was confirmed, she would proceed to rule out other fetal abnormalities, including fetal hydrops, as well as perform a fetal echocardiogram.

“While the size of this aneurysm was obvious on ultrasound, smaller free-floating aneurysms and other anomalies can be easily missed on a standard anatomy ultrasound.”

“While the size of this aneurysm was obvious on ultrasound, smaller free-floating aneurysms and other anomalies can be easily missed on a standard anatomy ultrasound,” she said.

If additional fetal anomalies are found, a genetics consultation would be warranted to discuss the potential risk of aneuploidy or other genetic conditions, and Patel says she’d recommend a diagnostic amniocentesis.

Upon diagnosing an umbilical vein aneurysm, Patel would consider administering betamethasone, depending on the gestational age, begin additional fetal surveillance, including fetal growth ultrasounds and Doppler studies, and schedule an earlier delivery, after all factors were considered.

“Every clinical scenario must be individualized and discussed in a multidisciplinary forum,” she said. “Our center and others that see rare cases like this will hopefully build on this case study to further delineate appropriate management and treatment options for future patients.”