Atherosclerosis may be accelerated in people with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), resulting in complex disease interaction driven by intertwined immunological and cardiovascular mechanisms. The latest research suggests a highly sensitive, positive-feedback loop between the conditions.

For the past 15 years, Amy Major, Ph.D., an immunology researcher at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, has been investigating why accelerated atherosclerosis is a leading cause of death for patients with lupus. For affected patients, she says LDL may be no higher than in patients who don’t have lupus, but the clinical differences can be significant.

In 2021, Major and Brenna Appleton, a graduate student in pathology, microbiology, and immunology at Vanderbilt, published a literature review on immune dysfunction and the mechanisms driving SLE-accelerated atherosclerosis. She also examined current methods for evaluating and treating the disease process.

“Lupus increases cardiovascular risk by a factor of five,” Major said.

“We know atherosclerosis is an independent predictor of cardiovascular risk in these patients. The question has been: does systemic inflammation constitute an additive effect to the risk of plaque rupture promoted by elevated LDL, or is there a different epigenesis?”

Major’s team is using animal models to research the roles of immune factors, especially T cells, involved in heart attack and stroke risk in lupus, and how and why drugs like statins, designed to treat cardiovascular disease (CVD), impact atherosclerosis in the setting of lupus.

Uneven Playing Field

About 1.5 million people in the United States live with lupus, a spectrum autoimmune disorder that may manifest in kidney disease, CVD, arthritis, or diseases affecting other organ systems. Patients in nine out of 10 cases are women, and people of color develop lupus at a significantly higher rate than whites.

“Cholesterol levels may be similar in lupus patients, but the CVD risk is still different than in someone without lupus,” Major said. “Plus, patients with lupus who are on statins or other lipid-lowering drugs may derive some benefit, but the impact is not equal compared to a patient without lupus.”

David Patrick, M.D., a Vanderbilt cardiologist and researcher with a special interest in CVD in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases, says that while premenopausal women are at very low risk in general, those with lupus have a 50 times greater risk of suffering a cardiovascular event, even in the absence of traditional CVD risk factors.

“I have seen young women with lupus in the ED suffering a heart attack,” Patrick said. “It’s terrible, and it’s a blind spot, I think, in the care of these patients. They are so different from most young women who come to a cardiology clinic with very low risk of these events.”

Plaques Not Homogenous

Major’s work in animal models focusing on T cells may help explain this uneven playing field.

“Lupus increases cardiovascular risk by a factor of five.”

T cells create an inflammatory environment, and plaques containing higher T-cell counts are more prone to rupture. Major and her team showed that mice that develop lupus and atherosclerosis have significantly more T cells present in plaques compared to controls, connecting lupus with the known proclivity for plaque rupture when T cells are elevated.

“Now that we see a pathway from increased inflammation from the disease, to plaque that has a higher T cell content, to higher thrombotic risk, is there a way we can manipulate this in patients so we can control their lipids?” Major asks.

Biomarkers for Risk Assessment

Major points out that existing CVD risk calculators fail to account for lupus-related differences. The literature suggests additional biomarkers might better identify patients at potentially high risk for CVD. These include increased circulating leptin, elevated homocysteine, the presence of soluble tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis (sTWEAK), as well as proinflammatory HDL (piHDL).

New research supports that serum sCD163, which is elevated in SLE patients, is also a promising biomarker for atherosclerotic CVD in lupus. An H131R functional polymorphism also confers CVD risk, specifically in the context of SLE, and could potentially act as a genetic biomarker in patients.

“I have seen young women with lupus in the ED suffering a heart attack. It’s a blind spot in the care of these patients.”

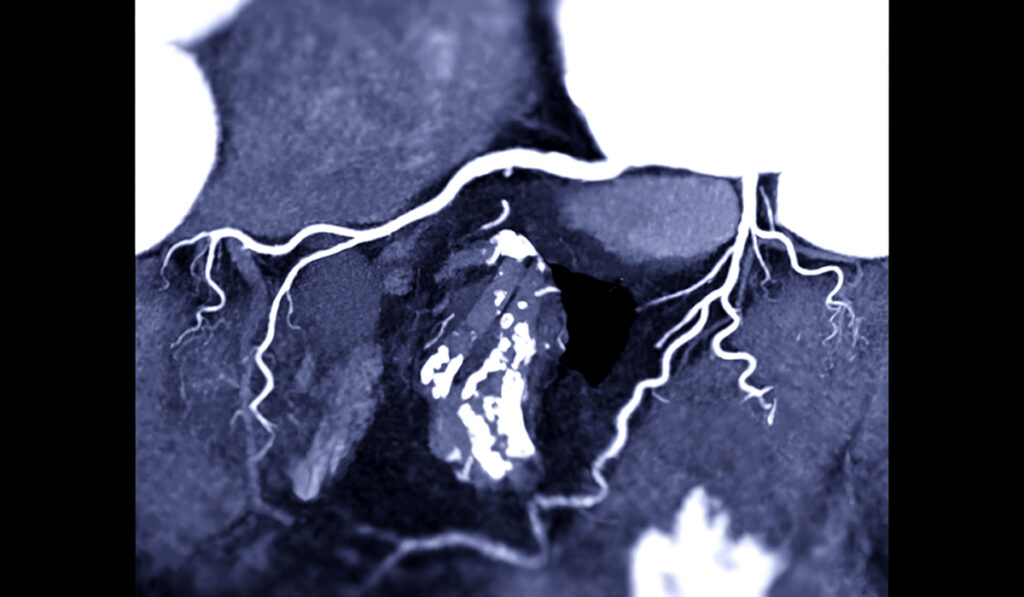

Patrick adds that the coronary artery calcification test continues to be an important clinical predictor of CVD development. Studies show that patients with lupus have over twice as much arterial calcification than patients without lupus.

Crossover Benefits Possible

Vanderbilt’s seminal research on the role isolevuglandins play in high blood pressure offers a related avenue for lowering CVD risk in lupus patients.

“We found that these isolevuglandins are really high in certain cells of patients with high blood pressure and lupus, and that they drive activation of immune cells,” Patrick said.

Clinical trials testing the nutraceutical 2-HOBA in patients with rheumatoid arthritis are underway, to see if this isolevuglandin scavenger lowers inflammation.

“If so, we expect this will have crossover significance for patients with lupus and other inflammatory autoimmune diseases,” Patrick said.