Hospitals in New York and overseas began seeing a small number of children who developed severe multisystem inflammation, with cases occurring one week to two months following an acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, in early 2021.

The symptoms overlapped considerably with those of acute COVID. Yet, as they began appearing in other states reaching COVID-19 peaks, researchers from Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt jumped in to differentiate the condition from COVID and other similarly presenting diseases in children.

“It’s a rare thing in medicine to be presented with a new disease – this one didn’t even have a name yet,” said James (Jim) Connelly, M.D., who co-leads the Comprehensive Hematology, Immunology and Infectious Disease Program (CHIIP) at Monroe Carell. “In the midst of the pandemic, we started meeting on Zoom on a very tight timeline to come up with an algorithm we could use to quickly and thoughtfully diagnose these patients we were beginning to see.”

The disease was finally designated as multisystem inflammatory disease in children (MIS-C), and its diagnostic prediction mode – which Connelly and colleagues developed – was recently published in ACR Open Rheumatology.

Monroe Carell researcher Sophie E. Katz, M.D., a pediatric infectious disease specialist who works in the MIS-C clinic, was a co-author.

“Making the right diagnosis early is crucial,” Katz said. “You want to give immunosuppressants to a child sick with MIS-C, but you don’t want to give them to a child battling an active infection. Making a mistake could lead to poor outcomes.”

Dangerous Confounders

A rare complication of COVID-29, MIS-C involves inflammation of two or more organ systems, which may include the heart, lungs, kidneys, brain, skin, eyes, or gastrointestinal organs. Children with the condition can develop myocarditis and acute kidney disease or go into heart failure.

“It’s a rare thing in medicine to be presented with a new disease – this one didn’t even have a name yet.”

“About half of these children are very, very sick and in the ICU,” Katz said. “Children have died from MIS-C, though not at our hospital.”

MIS-C symptoms can mimic those seen in Kawasaki disease; however, Kawasaki disease is more prevalent in younger children of Asian descent while prevalence of MIS-C is higher in Black or Hispanic children who also tend to be older, according to CDC data.

Other significant confounders among a diversity of patients are tick bites and other infections – viral or bacterial. MIS-C can even be mistaken for cancer.

“That’s another area where the distinction is vital to make,” Connelly said. “You certainly don’t want to give steroids to an undiagnosed leukemia patient.”

Addressing Limitations

The CDC’s broad, nonspecific description of potential MIS-C symptoms offered no definitive differentiators.

“We realized that we had this sizable cohort of febrile, hospitalized children who all had a mostly uniform workup,” Connelly said. “We asked ourselves: Can we look at those who ultimately had an MIS-C diagnosis in the hospital and use data collected in the first 24 hours to develop a predictive diagnostic system for identifying MIS-C patients early on?”

A thorough search for a diagnosis other than MIS-C would involve labs, imaging, EKGs and other tests that may not be scheduled right away, with some taking up to five days to come back. Such wait times may endanger children with MIS-C.

“You want to give immunosuppressants to a child sick with MIS-C, but you don’t want to give them to a child battling an active infection. Making a mistake could lead to poor outcomes.”

Patients at Monroe Carrell

Searching for distinguishing clinical variables, the researchers studied the charts of 127 inpatients evaluated for MIS-C at Monroe Carell between June 2020 and April 2021.

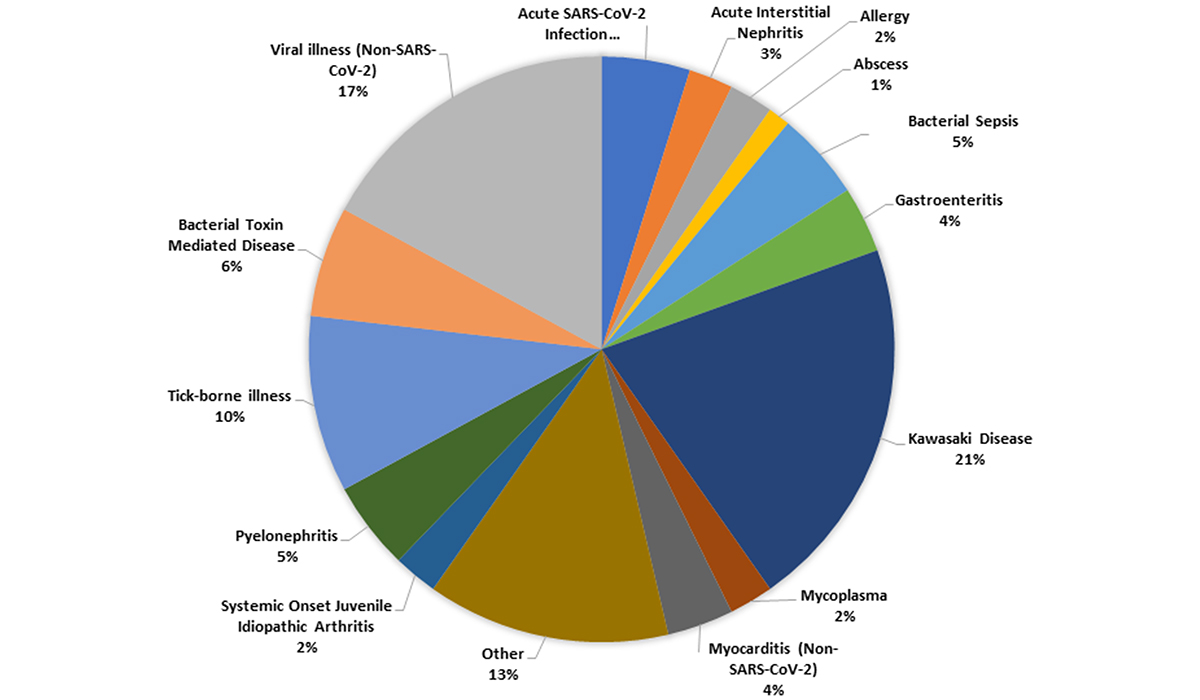

Of the 127 children, 45 were clinically diagnosed with MIS-C and 82 with other conditions. The most common of the other conditions were Kawasaki disease and viral syndromes unrelated to SARS-CoV-2 (21 percent and 15 percent, respectively).

The researchers isolated four variables determined to distinguish MIS-C: the presence of hypotension and/or fluid resuscitation, significant abdominal pain, new rash, and low serum sodium.

The charts examined by researchers showed the variables identified were strongly linked led to confirmed cases of MIS-C. By combining them with existing CDC or WHO guidelines, physicians will have more robust information, and thus more confidence, in diagnosing the disorder.

“This model discriminates MIS-C from other inflammatory syndromes – for example, infection, malignancy, and new onset rheumatic disease – and uses laboratory and cardiac data that can be available to clinicians within the first 24 hours of presentation to the ED,” Katz said.

Once treated, the patient’s symptoms soon improve, she added.

“With medicines to help with inflammation and blood pressure, a few days later they’re getting ready to go home.”

Next Step

The team plans to apply the model to other populations outside Tennessee, where certain conditions like tick-borne disease are not as prevalent and, perhaps, during a period when a different SARS-CoV-2 variant is dominant.

“If the model predicts MIS-C well using retrospective data at other large centers, we would like to study the model prospectively in new patients presenting with concern for MIS-C,” Connelly said. “The ultimate goal is to have a validated model for clinical use to help physicians accurately diagnose MIS-C in a timely manner.”