Anterior shoulder instability has received more research attention than posterior shoulder problems due to its frequency of occurrence. Yet, the military population provides an amplified view of posterior injuries, affecting as many as 24 percent of service members.

Lance E. LeClere, M.D., a former active-duty surgeon, joined Vanderbilt University Medical Center in the fall of 2021 as an associate professor of sports medicine after 15 years in the Navy. There, he was head team physician for the Naval Academy and an orthopaedic consultant for the Navy SEALs.

While at the Academy, he and Army colleagues Jon Dickens, M.D., and Kelly Kilcoyne, M.D., then at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, worked to develop a new arthroscopic technique using cadaveric distal tibia allografts to replace posterior glenoid bone loss. With five successful procedures in his portfolio, LeClere now brings that experience to Vanderbilt.

“The Naval Academy is kind of a shoulder instability factory, given the activities that are mandated through military training and varsity athletics,” he said. “So, it was really incumbent upon us, as active-duty surgeons, to systematically study this problem.”

The five patients who have undergone the procedure have experienced rapid and complete recoveries.

“We knew we were on to something when our first patient was doing push-ups in my office a little over three months after surgery,” LeClere said.

Bone Loss a Concern

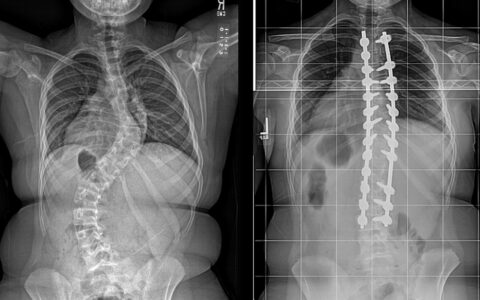

LeClere was principal investigator on a study of 443 servicemembers with shoulder injury that identified isolated posterior glenohumeral instability in 18 percent of cases and combined anteroposterior instability in 35 percent of patients. Fifty-three percent of patients had a tear that involved the posterior labrum, LeClere explained.

“There are good surgical solutions for bone loss in the front of the shoulder, but there have really not been great solutions for bone loss in the back of the shoulder,” LeClere said.

Many in this latter group have bone loss greater than 13.5 percent, a cutoff where bone augmentation rather than soft tissue-only procedures may be needed to avoid revision surgery. LeClere says the impact of this is often underestimated, with most repairs focusing only on the torn posterior labrum.

“We knew we were on to something when our first patient was doing push-ups in my office a little over three months after surgery.”

Common Approaches

Several techniques are used to augment the glenoid surface, including osteotomies, autograft transfers and allograft tibia transfers. Of these options, arthroscopic glenoid-based posterior capsulolabral repair with suture anchors, without bone augmentation, is the most commonly performed.

Historically, posterior bone augmentation procedures have been performed with an open posterior approach using autographs from the iliac crest. However, LeClere says surgeons face a “deep dark hole” when taking the posterior approach, with difficult surgical exposures, limited visibility, a deep surgical field and potential neurovascular complications.

“These challenges have led to decreased enthusiasm for posterior glenoid bone augmentation,” he said.

Arthroscopic Tibial Allograft

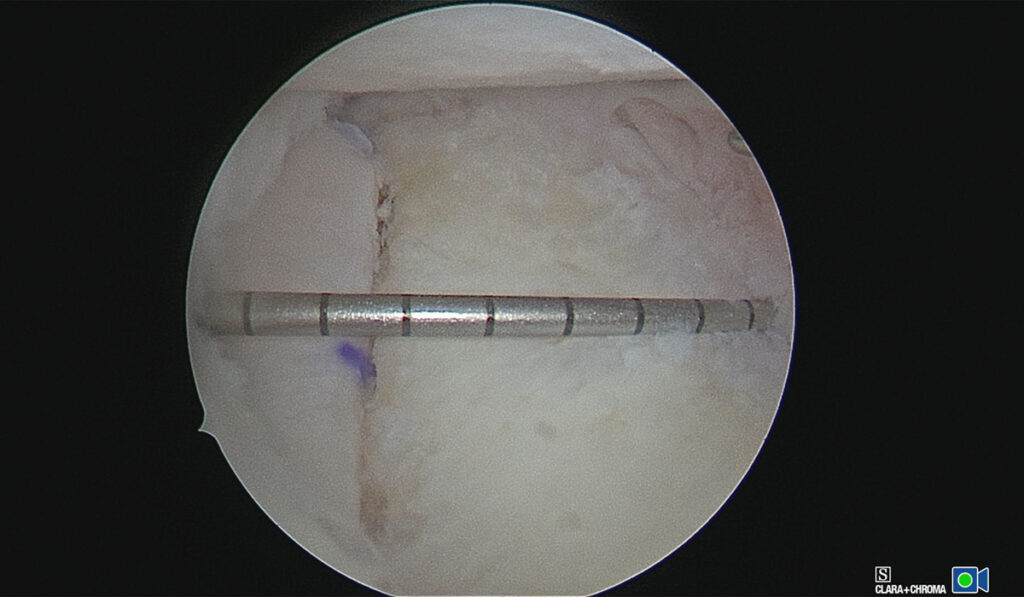

The technique LeClere and his collaborators developed deviates from this standard open posterior approach. Instead, the surgeon makes an initial arthroscopic incision with the patient in the lateral decubitus position and a second incision for passing the distal tibia allograft into the joint. Screws are placed through the graft percutaneously over the graft before the posterior labral tissue is mobilized and repaired to the native glenoid.

“There are good surgical solutions for bone loss in the front of the shoulder, but there have really not been great solutions for bone loss in the back of the shoulder.”

The team found cadaveric distal tibia to be an appealing graft, since it is similar in curvature to the glenoid articular surface, resurfaces posterior bone loss with articular cartilage, restores native glenohumeral contact pressures and avoids the morbidity of autograft harvest.

“The real beauty of the distal tibia, versus an iliac or other allograft, is we can make that graft as big as we think we need it,” LeClere said. “Plus, we can utilize the 3D-printed model of the patient’s glenoid and scapula to gain a full of understanding of the morphology of the bone changes and make precise allograft measurements, all prior to the surgery.”

Contraindications for this procedure include advanced glenohumeral arthritis, pain as a primary complaint without instability and multidirectional instability in the setting of hyperlaxity. However, LeClere says the majority of patients with posterior shoulder instability and bone loss stand to benefit.

Preventing Osteoarthritis

Now, LeClere is researching how the natural course of instability leading to osteoarthritis can be altered to preclude the need for total joint replacements.

“Certainly, we surgeons who have been treating this for a while have seen how untreated instability can progress to osteoarthritis,” he said. “But what we’re really lacking is data that tells us about progression risk to osteoarthritis with and without bone loss. Having that data will help us better stratify our patients by risk level and better pinpoint indications for surgical repair and posterior bone augmentation.”