Clinicians have a new reference tool to distinguish between Escherichia coli (E. coli) that are potentially commensal versus pathogenic in the urinary tract, thanks to careful cataloguing at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

In a data brief and associated article in the Journal of Molecular Biology, researchers published detailed microbiologic data and clinical symptomatology associated with 303 urinary isolates. The downloadable dataset can aid clinicians in determining whether an E. coli isolate is likely to cause asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) or urinary tract infection (UTI)/cystitis.

“There are currently no clinical tests that differentiate asymptomatic bacteriuria from symptom-associated urinary E. coli isolates,” the authors wrote. “Here, we are able to group isolates by patient symptom status, which allows us to look for predictors of disease state or identify potentially diagnostic biomarkers.”

Asymptomatic Colonization

Leading the effort is Maria Hadjifrangiskou, Ph.D., associate director of the Vanderbilt Institute for Infection, Immunology and Inflammation. Hadjifrangiskou has spent over a decade studying E. coli pathogenesis and host interactions. E. coli is the most common cause of UTI, she says, but can also colonize the urogenital tract asymptomatically.

“The same species that cause a UTI can then be found in the urine of healthy patients without any associated signs or symptoms,” Hadjifrangiskou said. “A major challenge in preventing and managing UTIs is distinguishing strains that actually cause them.”

“A major challenge in preventing and managing UTIs is distinguishing strains that actually cause them.”

A Comprehensive Assessment

Hadjifrangiskou’s team used Vanderbilt’s MicroVU infrastructure to link the urinary E. coli isolates to deidentified EHR data (including sex, age, collection setting, associated infections, recent catheterization, pregnancy, diabetes, urinary tract abnormalities, asymptomatic bacteriuria, immune status and associated infection). All of the isolates were found in patient urine samples at levels higher than 100,000 colony-forming units per milliliter.

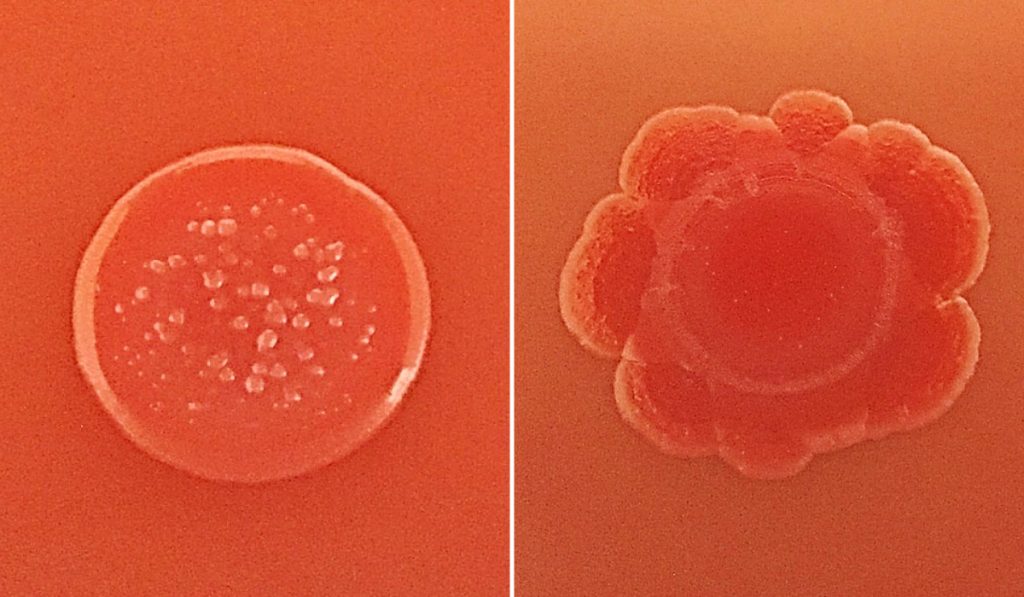

The isolates were grown in human urine at both atmospheric and low oxygen levels (akin to the hypoxic bladder environment). Then, isolates were subjected to morphologic assessments and biofilm assays.

Researchers also used liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry to compare metabolites released into the growth media by asymptomatic bacteria and cystitis-causing bacteria. In total, the team identified 6,711 distinct compounds produced by the growing bacteria, of which 429 were identifiable in existing libraries and showed statistical differences in abundance between the two groups of E. coli.

“These data can be used as a tool to distil a metabolic signature to differentiate ASB- and cystitis-associated E. coli strains,” the authors wrote.

Distinct Differences to Inform Diagnosis

The two groups of E. coli had variable colony morphologies that cannot be used to distinguish disease-causing isolates. Similarly – and surprisingly – the ability of an isolate to form a biofilm in vitro did not correlate with any disease symptoms. However, the researchers say rates of Congo red dye uptake may be something that could help clinical laboratories rapidly distinguish isolates most likely to cause UTI.

“These data can be used as a tool to distil a metabolic signature to differentiate ASB- and cystitis-associated E. coli strains.”

A deeper dive into the metabolomic data found lower guanosine and higher adenosine taken up by asymptomatic E. coli versus UTI-associated isolates, which suggests distinct mechanisms may underlie nutrient uptake in the groups. Said Hadjifrangiskou, “In the future, we can apply additional algorithms to test for phenotype-clinical outcome and genetic associations that may not have been incorporated here.”

A Wealth of Strategies to Evade Detection

E. coli have a wide variety of virulence factors to support asymptomatic colonization. These include adherence factors, nutrient scavengers, and quorum sensing molecules used for communication. As one example, published in Nature Communications, Hadjifrangiskou and colleagues showed uropathogenic E. coli can create a safe haven in vaginal cells to evade immune detection.

Each isolate’s arsenal is slightly different. Hadjifrangiskou says the extensive phenotypic heterogeneity among E. coli isolates rarely correlates with clinical symptoms. Instead, precise molecular signatures, compiled from large collections of isolates like those in the present study, are required to dissect the matter of colonization versus infection likelihood.

“If we are able to pinpoint metabolic differences that can be detected with a colorimetric assay in urine, combined with a possible genomic signature,” she said, “we hope in the future to have a robust and reliable tool to quickly decipher the isolates likely to cause infection and reserve antibiotic use for those.”