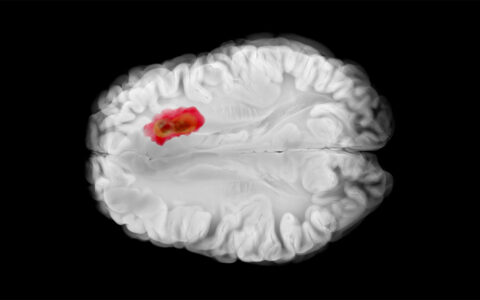

For nearly 40 years, cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) have been performed in combination for peritoneal malignancies. Even with the procedure, cure rates are negligible, but with careful disease scrutiny, many patients stand to gain years of extended life over receiving systemic therapy alone.

Deepa Magge, M.D., an assistant professor of surgery in the Division of Surgical Oncology and Endocrine Surgery at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, is a specialist in CRS-HIPEC for peritoneal surface malignancies. She says appropriate patient selection and timing of referral and intervention can make the difference between improving prospects or a futile effort that causes more morbidity.

“While there are outliers, recurrence is a given for most types of cancers in this region,” Magge said. “What we are doing is more effectively pushing recurrence into the future. However, the procedure is not for all comers. It depends on the biology of the patient’s disease, the pathology of their disease, their age and comorbidities, and their goals.”

Narrowing the Net

At one time, CRS-HIPEC was broadly indicated for patients with gastric cancers and high-grade tumors. “Today, we are not casting such a wide net,” Magge said. “Now we are seeing the procedure accepted only for specific indications where we know it can make a difference.”

Casting a narrower net is supported by research. Magge worked on a study that showed improved outcomes in the second of two five-year periods studied for comparison. She says the improvement was primarily due to increased experience, better patient selectivity and greater discretion to abort a procedure pre-HIPEC if the tumor burden was higher than expected or small bowel was significantly involved.

“The procedure is not for all comers. It depends on the biology of the patient’s disease, the pathology of their disease, their age and comorbidities, and their goals.”

“Outside these narrower selection parameters, an infinitesimal number of people were helped by the procedure,” she said. “Focusing treatment on select patients means we aren’t burdening others with an unnecessary ordeal or causing them to stop helpful systemic therapy.”

Disease and Timing Variables

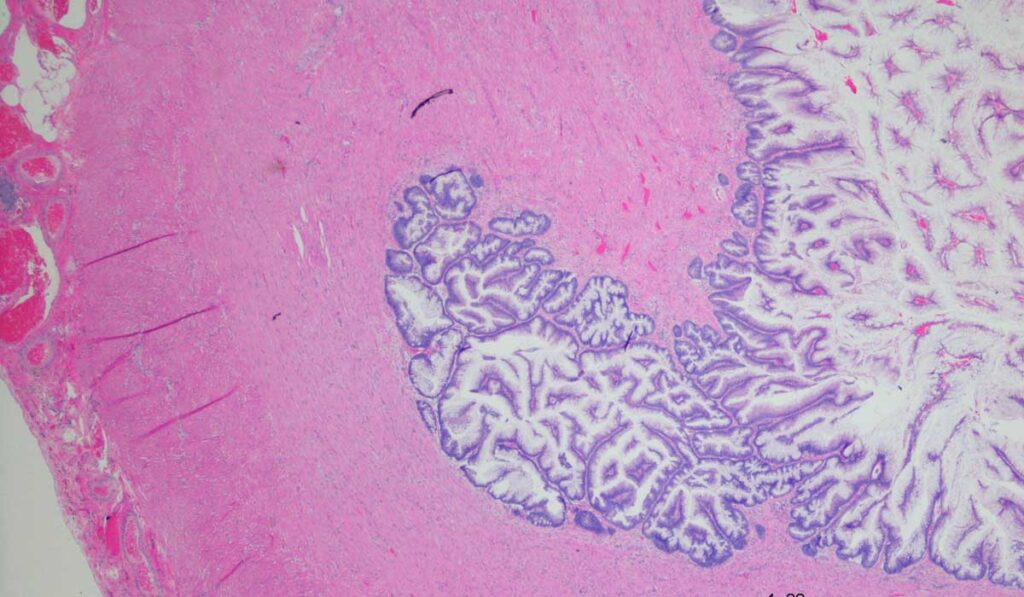

Appropriate candidates for the procedure, Magge explains, are patients with appendiceal cancers that are low-grade mucinous neoplasms with peritoneal disease. “These malignancies are fairly indolent and unresponsive to systemic therapy, so CRS-HIPEC is often a first-line therapy,” Magge said. “By debulking and targeting residual cells, recurrence can be deferred by many years because the cancer is not aggressive. This is particularly true if the tumor burden is low.”

Magge recommends a different approach for high-grade adenocarcinomas of the appendix, which tend to be responsive to chemotherapy. In these cases, CRS-HIPEC would require taking the patient off chemotherapy for three to six months, which she says would be counterproductive.

“These patients need six months of chemotherapy up front and monitoring of significant disease progression. Then, if they have responded and have minimal disease burden, we may do the procedure,” Magge explained.

“Focusing treatment on select patients means we aren’t burdening others with an unnecessary ordeal or causing them to stop helpful systemic therapy.”

On the far end of the spectrum, patients who have a high tumor burden are not good candidates for the procedure, regardless of the biology. In the gray zone are patients who have an appendiceal cancer with limited tumor burden that have responded well to systemic therapy. “They might be candidates if you believe you can do a complete debulking and get out all the disease,” Magge said.

Other Factors Impacting Candidacy

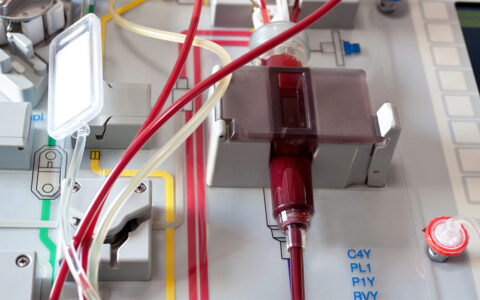

Magge says fragile patients are particularly vulnerable to surgical complications of CRS-HIPEC. The resection of disease and organs may be extensive, and the patient undergoes hemodynamic changes that lower blood pressure and increase heart rate.

“You have to really look at the likelihood that they’re going to have new disease or more disease three months down the road,” Magge said. “If they have comorbidities and a high likelihood of surgical complications, it doesn’t make sense to do the procedure because the cost may outweigh the benefit.”

A Source of Hope

Magge sees survivors of mucinous neoplasms many years out from their surgery. “While it isn’t really a curative procedure, it can reset the clock up to 10 or 12 years for low-grade tumors.”

She even sees one patient with a high-grade adenocarcinoma of the appendix seven years out from his surgery. “This procedure is definitely a source of hope for many patients, and deservedly so,” Magge said.