The heart donor pool has grown due to the ability to safely use hearts from hepatitis C+ donors. Now, mounting successes in donation after cardiac death (DCD) heart transplants could further narrow the gap between supply and demand, increasing overall heart transplantation volume by over 20 percent.

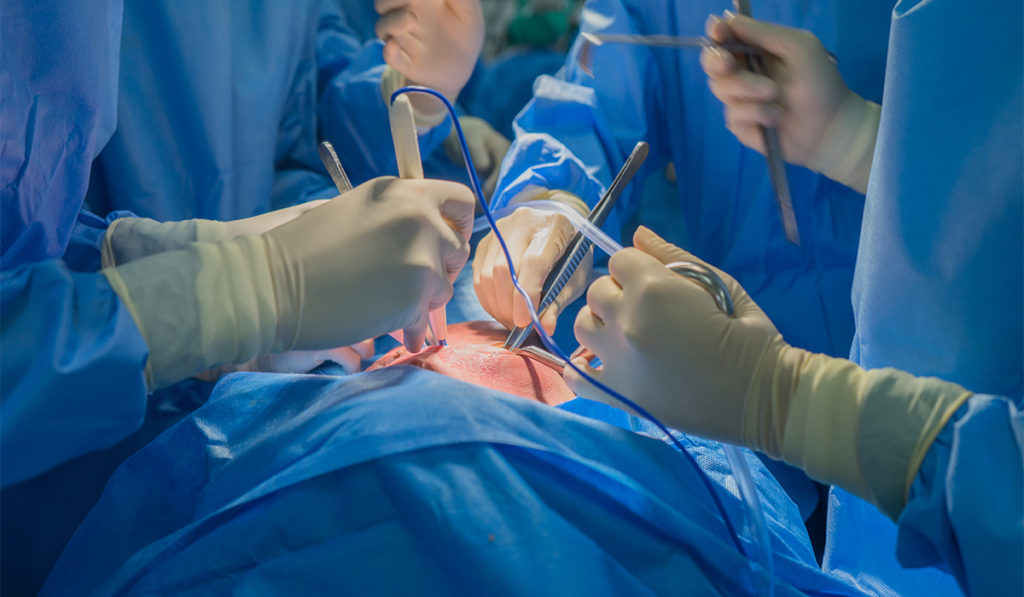

In 2019, surgeons began using the TransMedics Organ Care SystemTM in DCD procedures. Vanderbilt Heart and Vascular Institute is one of six sites recruiting for a clinical trial to evaluate the system’s utility in reanimating DCD hearts and identifying hearts that are good candidates for transplant.

Since December 2019, six of seven adults at Vanderbilt are recovering well after receiving DCD hearts. Four have been discharged home. “We saw no test results in these patients that deviated far from the mean of our other transplant patients,” said Ashish S. Shah, M.D., chair of the Department of Cardiac Surgery. “Importantly, these are hearts that would never have been used without the DCD option. It truly is a new frontier in heart transplantation.”

More Hearts Put to Use

Historically, heart donors had to meet the strict criteria of brain death. Viable hearts have been discarded even as other organs were harvested from the same donor, Shah said.

For a DCD transplant, a donor’s heart can be used if they died naturally or from cardiac arrest after life support was discontinued, and if they did not die from cardiovascular disease.

Before the explant can occur, death must be irreversible, which the Institute of Medicine reports as occurring within 60 seconds of cardiac arrest. Often these hearts are superior because they evade the long brain death process that can damage the heart, Shah said.

Widening the Transplant Window

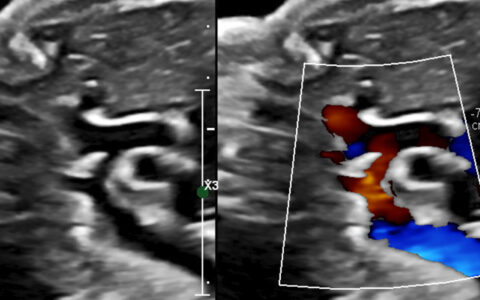

Ischemic injury is the key risk to be managed in heart transplant. “The major concern with any transplant is the period of time when the heart is receiving no blood or oxygen prior to infusing it with the preservation solution and ice,” Shah said. “This period can vary considerably and may injure the heart permanently.”

While harvesting a DCD heart may magnify timing challenges, the TransMedics system helps manage this risk by perfusing the heart in warm blood within minutes of explant. It also enables assessment of the heart’s viability by measuring serum markers of injury. Traditional cold storage has not allowed surgeons to assess the heart’s function for signs of damage.

With the TransMedics system, viability and damage can be assessed through direct recovery and in vivo perfusion of the heart, or ex vivo normothermic regional perfusion followed by cold storage, the method used at Vanderbilt.

Expanding DCD Transplant

Sixteen centers are expected to participate in the trial, but ramping up this alternative to traditional transplant won’t happen overnight, Shah said. “Certainly, DCD will increase the number of donors, but there are still logistical things that will make this more difficult for smaller centers, and there will be a need for more expertise among the recovery teams.”

“DCD will increase the number of donors, but there are still logistical things that will make this more difficult for smaller centers.”

Shah sees COVID-19 ushering in an era of greater DCD transplant collaboration between medical centers. With commercial flights limited or off-limits, and with some hospitals strained from heavy COVID-19 patient loads, surgeons are becoming more resourceful about securing viable hearts for recipients with urgent needs.

“Just this Mother’s Day, Boston Mass put a DCD heart on the TransMedics device, and a couple of their team members brought it here in a transport van for a patient of ours – a young girl who was running out of time.” Shah said.