More than a billion dollars in federal funds have been allocated to prevention and treatment programs for opioid use disorder. The COVID-19 outbreak places new stresses on this effort, with social distancing rules and fears of contracting the virus impacting areas of outreach and treatment including peer counseling, in-person evaluations and therapy, access to medications for opioid use disorder and syringe exchange programs.

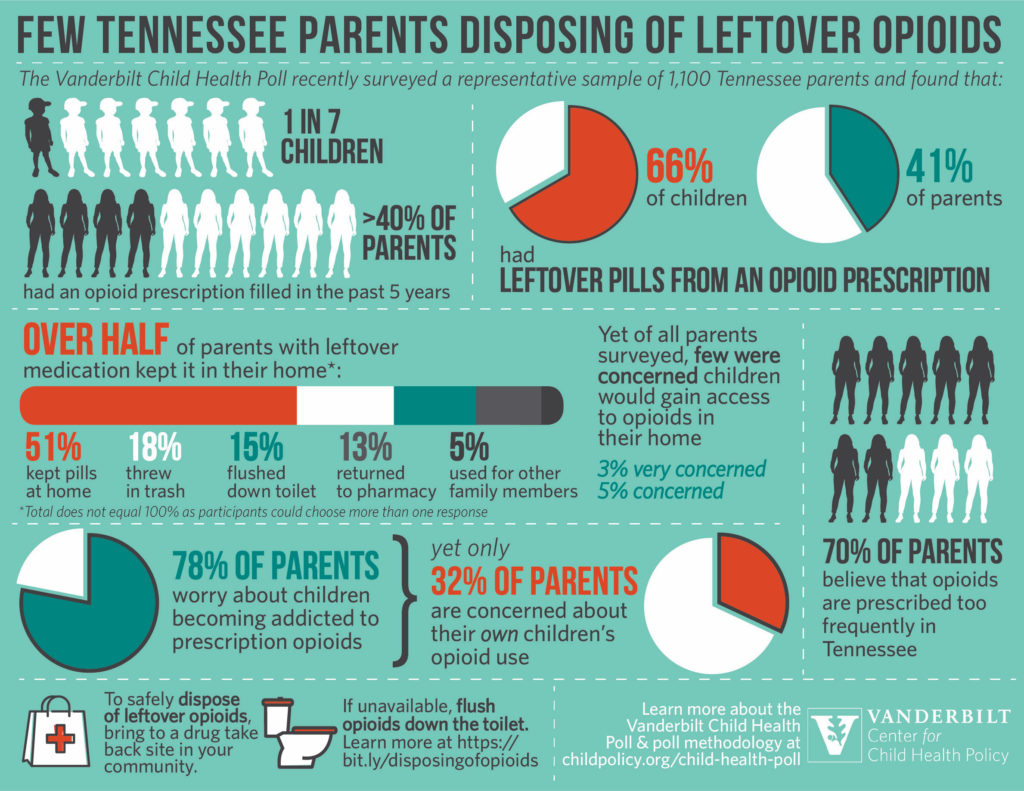

One new area of concern is that children have increased access to opioids as they spend most of their time in the home, says Stephen Patrick, M.D., a neonatologist and director of The Center for Child Health Policy at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt. Patrick organized a recent poll of 1,100 Tennessee parents about the opioids on hand in their homes and their risk awareness.

Too Few Concerns?

Alarmingly, while most parents reported general concern about the danger of opioid access in the home, they were less concerned about their own children accessing opioids kept on hand after their prescribed use.

“Parents have not gotten the message that leftover opioids in their homes are dangerous. Providers and pharmacists need to remember to give clear instructions to patients on how to dispose of opioids, and policymakers need to enhance efforts to promote and enable safe disposal,” Patrick said. He has publicized the poll data as part of an effort to raise public awareness.

“Parents have not gotten the message that leftover opioids in their homes are dangerous.”

Parents’ Blind Spot

Opioid prescriptions are steadily increasing for adults and children, under varying prescribing guidelines. Patrick’s poll found that more than 40 percent of parents and one in seven children were prescribed an opioid in the past five years.

Over half of the parents polled keep leftover opioid medications in their home. “Parents may overestimate their control over their own children’s access or susceptibility to the pills. Seventy-eight percent say they worry about children becoming addicted, yet less than a third were concerned about their own children’s potential opioid use,” Patrick said. “The numbers don’t add up.”

COVID-19 Stress Points

When kids are home and more socially isolated from friends, school, sports and other extracurriculars, their anxiety ratchets higher, Patrick said. Individually, these stresses don’t make the top ten list on the Holmes and Rahe Life Change Index, but the cumulative effect could be equivalent to some of the most traumatic events on that scale, like the death of a close family member or a parental divorce.

“The pandemic has been a shock to the system in so many ways – particularly to kids attempting to do school, attempting to do other things they normally do,” Patrick said. “Having opioids around the house may be a greater temptation.”

Forming the Disposal Habit

Patrick says anonymous pharmacy drop-off is the safest option for families to dispose of opioids. While the “flush list” method is FDA-approved, it is a distant second best. The FDA also describes a process for disposal in household trash. Securing drugs in locked medicine cabinets, lock boxes or gun cases can be another means of maintaining a safe home.

The challenge is to ingrain safe disposal practices as a habit, Patrick says. “As providers, we need to make sure we are having the disposal conversation with the patient when we prescribe opioids.”

On a larger level, he hopes to see addiction prevention and care better embedded into primary care, obstetrics and gynecology, and pediatrics – so that opioid education is in the hands of providers who see patients most often.

“A buprenorphine waiver requires only eight hours of a provider’s time, enabling them to treat patients with opioid addiction,” Patrick said. “This pandemic is bringing the urgency of better prevention and treatment options out in bold relief.”

“We need to make sure we are having the disposal conversation with the patient when we prescribe opioids.”