Adult congenital heart disease (ACHD) is developing from narrow niche to specialty, thanks to higher survival rates for the 1 out of 100 babies born with a heart malformation. An estimated 1.4 million adults are living with ACHD in the U.S. today, for the first time exceeding the number of children with congenital heart disease.

The opportunity for patients to live longer, healthier lives brings with it the need for more complex evaluation and decision-making. While many ACHD patients never face the need for transplant or other surgeries, for others the heart will fail without intervention.

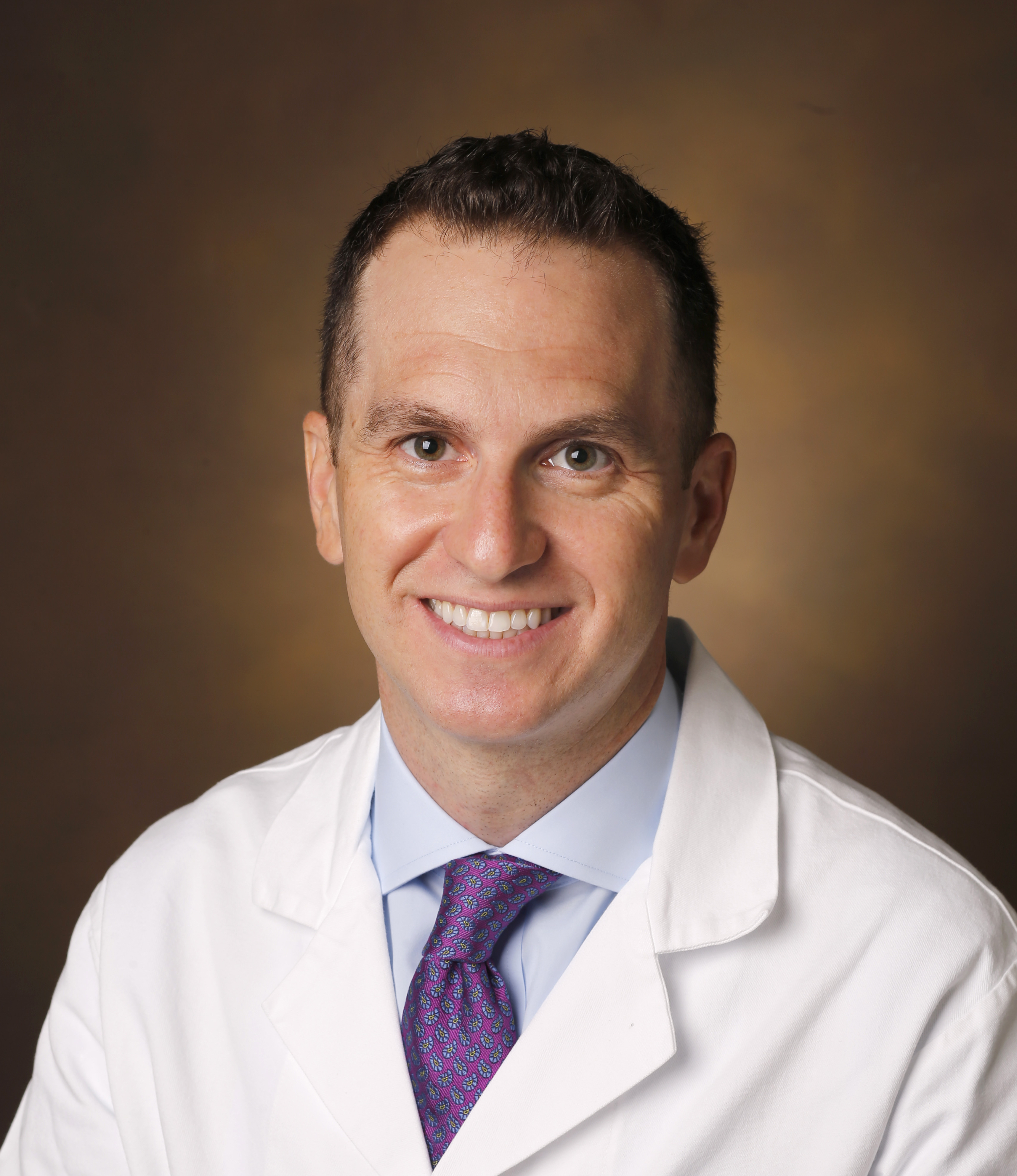

“Heart failure is the number one cause of death in ACHD, and yet these patients are less likely than those with other etiologies to undergo transplant or have a ventricular assist device (VAD),” said Jonathan Menachem, M.D., an assistant professor in cardiology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. “There is an increased need for ACHD patients to have access to multi-specialty teams that include ACHD, heart failure and transplant cardiologists and surgeons.”

“These patients are less likely than those with other etiologies to undergo transplant or have a ventricular assist device.”

At Vanderbilt, the transplant group has developed a unique program, which Menachem leads, in Advanced Congenital Cardiac Therapies (ACCT). The goal is to support ACHD patients with multidisciplinary evaluations for transplantation or VAD.

Patient Advocacy

Menachem is a devoted advocate for improving ACHD patients’ access to advanced heart failure therapies. He has presented at national conferences on the topic of providing dedicated programming for ACHD patients as well as collaborating with medical teams locally, regionally and nationally.

“Because each of these patients is slightly different, we lack the kind of large scale data that we have for things such as coronary artery disease or atrial fibrillation. With that being the case, interactions between multiple institutions are necessary to improve our outcomes,” Menachem said.

Board certification for ACHD has only been available since 2015, so the number of specialists trained to care for these patients lags in comparison to the total number living today. This can delay care, worsening outcomes.

Additionally, in the current heart transplant allocation system, most ACHD patients are listed at a relatively low status, despite often being as medically fragile as patients who meet criteria for a higher ranking. Menachem regularly petitions UNOS for ACHD exceptions, often with positive results.

“It’s not uncommon for us to petition UNOS to have these patients listed at a higher status,” said Kelly Schlendorf M.D., medical director of Vanderbilt’s Adult Heart Transplant program. “Those of us who review and vote on petitions like these recognize that ACHD patients are unique and many of them are much sicker than initially recognized. The goal is to get them to transplant before they’re too sick to be candidates.”

“The goal is to get them to transplant before they’re too sick to be candidates.”

Increasing Transplant Access

Menachem encourages referrals to high-volume heart transplant centers like Vanderbilt for expertise that a multi-specialty team of ACHD, heart failure and transplantation experts can provide. “Thoroughly evaluating these patients before their health becomes fragile is the goal we all share,” he said. Close to 100 ACHD patients have been evaluated at Vanderbilt over the past several years, with 14 undergoing transplant and four receiving a VAD.

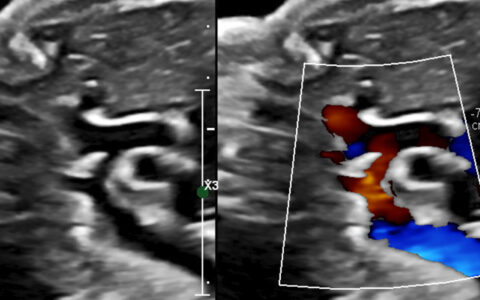

The majority of patients Menachem sees have complex conditions like tetralogy of Fallot, transposition of the great vessels, or single ventricle physiology. Single ventricle patients are the most complex, but a 29 year old patient, whose parents were told would not live past age five, underwent a combined heart and liver transplant about a year ago.

“He is feeling well, and is now engaged to another single ventricle patient – who also underwent transplant – that he met through this process!” Menachem said.