Ibrutinib, a highly potent kinase inhibitor, has been effective in the treatment of B cell cancers, but a recent study in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology connected ibrutinib to several cardiovascular adverse drug reactions (CV-ADR). The study showed between 10 and 20 percent of these adverse reactions were associated with fatalities.

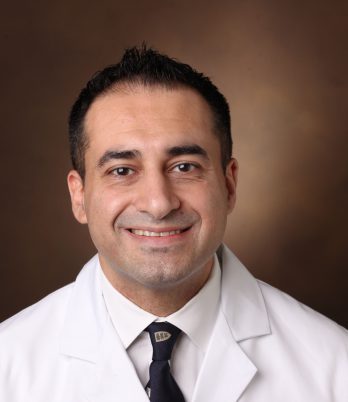

“We are becoming more aware of adverse reactions now that the drug has moved to the front-line setting,” said Javid Moslehi, M.D., senior author on the study and director of the Cardio-Oncology Program at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

“We are becoming more aware of adverse reactions now that the drug has moved to the front-line setting.”

Moslehi is part of a research team at Vanderbilt focusing on toxicities associated with targeted therapies, immunotherapies, and other new treatments. “Ibrutinib is a very successful drug,” said Joe-Elie Salem, M.D., first author of the study and adjunct associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt. “We have to understand these adverse reactions better.”

Identifying the Risks

Ibrutinib specifically targets a kinase activated in various B cell malignancies, like chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Fatalities associated with ibrutinib were first reported in 2018 following a randomized trial assessing the effectiveness of ibrutinib as front-line treatment for CLL.

The 2018 study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, found that despite improvement in progression-free survival at two years, there was no significant difference in overall survival between groups receiving ibrutinib and the control group. Death rates reached seven percent in each ibrutinib group compared to one percent in the control group.

“The cancer got better, but that didn’t mean people were living longer,” Moslehi explained. “That suggested to us that the benefit from the cancer perspective was offset by something else.”

“The cancer got better, but that didn’t mean people were living longer.”

Cardiovascular Adverse Drug Reactions

In their follow-up study, Moslehi, Salem and colleagues used VigiBase, the World Health Organization’s database of individual case safety reports, to complete the most extensive clinical characterization of CV-ADR associated with ibrutinib to date.

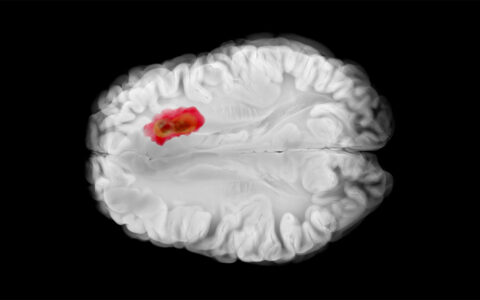

The study identified severe cardiovascular toxicities associated with ibrutinib, including supraventricular arrhythmias (SVA), central nervous system (CNS) hemorrhagic events, heart failure (HF), ventricular arrhythmias (VA), conduction disorders (CD), CNS ischemic events and hypertension. Two of the CV-ADR identified – HF and CD – are new findings.

“We generally treat patients with atrial fibrillation or arrhythmias with blood thinners,” Moslehi said. “The problem is that ibrutinib also thins the blood. These patients, who already have a bleeding risk from ibrutinib, were effectively getting treated for atrial fibrillation with blood thinners and then suffering a brain hemorrhage.”

The median time from the start of treatment with ibrutinib to the onset of CV-ADR ranged from less than a month for conduction disorders to four to five months for hypertension. CV-ADR mostly affected older men, and the average age of affected individuals was between 70 to 80 years.

Fatalities were associated with about ten percent of SVA and VA cases and about 20 percent of CNS events, HF and CD cases. Ibrutinib-associated hypertension was nonfatal.

Future Research

Moslehi says an increased understanding of those at higher risk of developing CV-ADR is needed to foster a personalized medicine approach and prevent complications.

The research team is currently investigating which pathway is being affected by ibrutinib to lead to cardiovascular toxicities. In addition, Moslehi and colleagues in the Vascular Medicine Program at Vanderbilt were recently awarded a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute to study the effect of tyrosine kinase inhibitors on the vascular system.