Many think the effects of daylight savings time (DST) are limited to a few days each year when clocks “fall back” or “spring forward.” Everyone can cope with those infrequent disruptions that bring changes to sleep schedules.

But sleep experts have found clinical implications of DST last much longer. “It’s not one hour twice a year. It’s a misalignment of our biologic clocks for eight months of the year,” said Beth Ann Malow, M.D., a professor of neurology and director of the Sleep Disorders Division at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Raising Awareness

Malow recently coauthored a peer-reviewed commentary in JAMA Neurology highlighting challenges associated with the transition to DST and the return to standard time that follows. Her co-authors are Kanika Bagai, M.D., also of the Vanderbilt Sleep Disorders Division, and Olivia Veatch, Ph.D., of the University of Pennsylvania.

“Twice a year, in the spring and fall, our sleep division gets requests from news media to talk about DST,” Malow said. “And every year we pull up evidence about its detrimental effects on health and wellbeing. As sleep specialists, we started thinking, why don’t we just get rid of it?”

“Every year we pull up evidence about its detrimental effects on health and wellbeing. As sleep specialists, we started thinking, why don’t we just get rid of it?”

Biological Implications

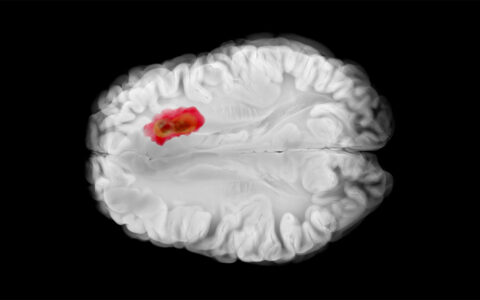

The transition to DST is associated with increased risk of heart attack and ischemic stroke, plus other negative effects of partial sleep deprivation. Average sleep duration shrinks by 15 to 20 minutes for adults during DST transitions, which may increase the risk of fatal accidents.

While some people may have more flexible circadian rhythms, others are more sensitive. Children and people with neurological conditions may be more affected. Malow cites evidence showing even slight temporal disruptions, like living on different sides of time zones, can be enough to affect a person’s rhythms.

The effects of daylight savings time can alter the epigenetics of core circadian clock genes. Over time, DST eliminates bright morning light that critically synchronizes biologic clocks.

“Our biologic, natural sun and social clocks have drifted apart.”

This can have major implications for circadian rhythms, says Carl Johnson, Ph.D., a biophysicist and chronobiologist at Vanderbilt. “Our biologic, natural sun and social clocks have drifted apart,” Johnson said. “The body clock never fully adjusts to DST. A return to standard time would more closely align with natural light cycles.”

Call to Action

While the sleep and circadian communities believe returning to standard time may be more biologically appropriate, gaining political buy-in for a nationwide change remains a challenge.

The Department of Transportation is responsible for enforcing DST. However, many states have taken it upon themselves to propose alternative DST legislation. Since 2015, several states have passed allowable DST exemption laws. Others, like Tennessee, have passed legislation supporting permanent DST, although the U.S. Congress will need to amend current legislation to allow states to implement permanent DST.

“The politics are fascinating,” Malow said. “We have states bordering on different parts of time zones, industries that span time zones, agriculture, school start times, and many other factors to consider.”

Locally, Malow has been an advocate for making school start times later, as even a small switch from 7:20 a.m. to 7:40 a.m. can make a big difference for middle and high school students. California recently passed legislation mandating start times of 8:30 a.m. or later for high school students.

Malow is hopeful the JAMA Neurology commentary might help raise awareness of acute and chronic health effects of DST and fuel consensus to eliminate it.