Most cases of prostate cancer are caught locally and successfully treated by surgical removal or radiation therapy. Treatment options for metastatic cancer, however, can only slow the spread of disease, but not cure it.

“We just don’t have enough agents to get people into good remissions or control the disease extensively,” said Austin Kirschner, M.D., assistant professor of radiation oncology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. “We would love to make it so that even metastatic prostate cancer is controlled as more of a chronic illness.”

Kirschner is the lead investigator on a preclinical study recently published in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer reporting that combining immunotherapy with radiotherapy may improve outcomes for patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Drawing Immune Cells to the Tumor

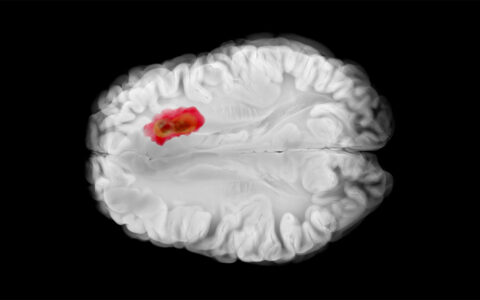

Prostate tumors are poorly responsive to immunotherapy because they are ”cold” tumors, meaning they lack an active immune response.

“A key feature of prostate tumors is that they don’t really have any good immune infiltrates,” Kirschner said. “We triggered the immune infiltrate by treating with radiation.”

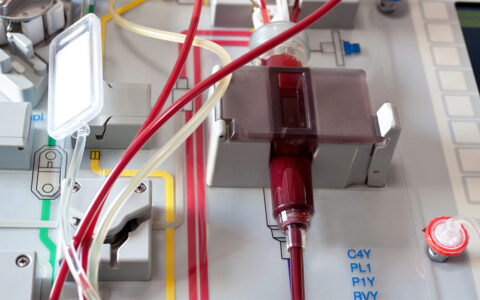

Pairing radiation therapy with cancer immunotherapy is an emerging clinical treatment paradigm. Although previous clinical trials have reported promising results when combining x-ray radiation therapy with ipilimumab for the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer, the findings were not robust enough to sway clinical practice.

These studies struck a chord with Kirschner, and he thought perhaps higher doses of radiation than those tested in the studies are required to trigger a sufficient immune response.

“What we’ve learned is that eight gray radiation, which is what they were using, is just barely at the beginning of where you start seeing an immune response. When you get to higher doses, like 10 or 20 gray, you get a stronger response.

An All-Around Success

“You can put two tumors in a mouse, treat one of them with radiation, and both tumors respond to the drug treatment – the radiation makes both tumors respond.”

Kirschner and his research team established two tumors in different locations in a mouse model of castration-resistant prostate cancer. The mice were treated with either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibodies and one of the tumors was irradiated with a total of 20 gray radiation in two fractions. The dual approach caused regression of the irradiated tumor as well as the unirradiated distant tumor.

“We call it an abscopal effect, meaning it’s outside the scope of radiation in the field,” Kirschner explained. “You can put two tumors in a mouse, treat one of them with radiation, and both tumors respond to the drug treatment – the radiation makes both tumors respond.”

The researchers also found that the combination of radiation therapy with cancer immunotherapy significantly increased survival. Compared to antibody treatment alone, the median survival was 70 to 130 percent longer when radiotherapy was combined with anti-PD1 or anti-PD-L1, respectively.

Optimizing the Approach

Kirschner is currently working to determine the best dose and the right sequencing. “The concept that we published about was sufficient to get a response, but it might not be optimal. For example, if we increase the radiation dose a little bit, do we get a better response?”

“Another big question is how to sequence them,” Kirschner said. “Should you give the radiation first or the drug first? Or should you give them at the same time? We’re testing a landscape of treatment variations to see where the best response can be seen.”

He is also hoping to follow up with a clinical trial. “My motivation comes from seeing patients who are very poor off, don’t have good options, and need more help. We want to see whether this approach could be used as an alternative to other agents or as a new line of therapy.”