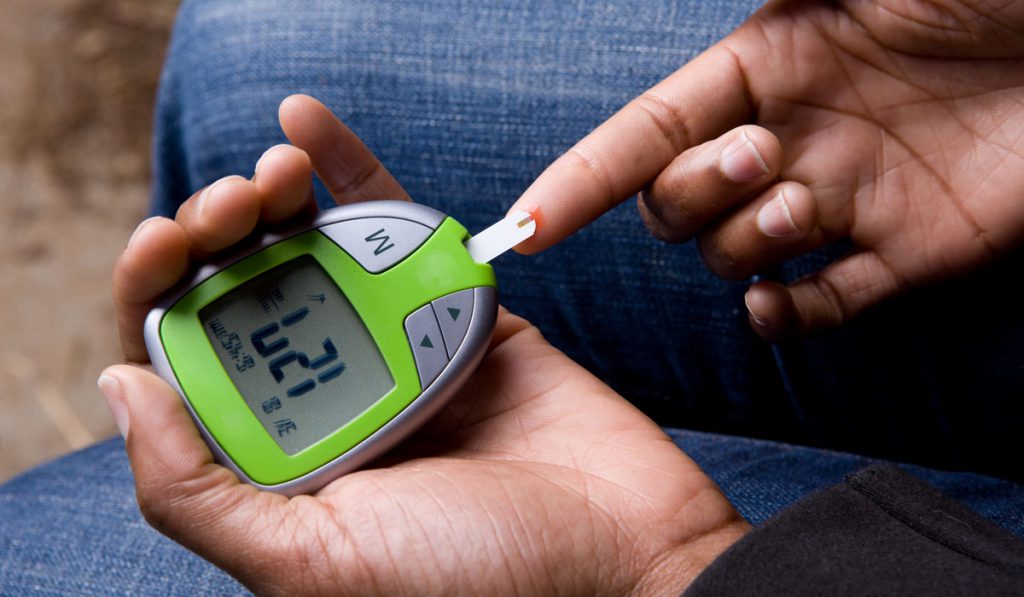

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates 13 percent of black, non-Hispanic Americans have received a diabetes diagnosis, compared to only 7 percent of white, non-Hispanics. Racial and ethnic disparities have persisted for decades, often translating to poorer outcomes for minority populations.

“We’ve known about racial disparities in type 2 diabetes, but what hasn’t been clear is exactly why they occur. There are a lot of inconsistencies in outcome determinants that need further study,” said Lyndsay A. Nelson, Ph.D., research assistant professor at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

In a recent study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Nelson and her colleagues adjusted patient data for socioeconomic status (SES) to reveal risk factors that contribute to worse diabetes outcomes among black, non-Hispanic Americans.

Identifying Risk Factors

For the study, part of a larger randomized controlled trial, Nelson and Lindsay Mayberry, Ph.D., assistant professor of medicine at Vanderbilt, teamed up with colleagues from the Department of Biostatistics. The researchers recruited 444 adult patients with type 2 diabetes from local primary clinics (45 percent non-Hispanic blacks, average age 56 years). They asked participants to self-report demographics and SES indicators (income, education, health insurance, housing status, and financial strain). Participants also completed measures assessing health literacy, numeracy, and self-care behaviors—and had an HbA1c test.

The researchers then assessed differences between black and white participants in each of the determinants of diabetes outcomes, first unadjusted, then adjusted for SES using propensity score weighting.

Finding Differences

In unadjusted analyses, non-Hispanic blacks had lower health literacy and numeracy—the ability to understand and work with numbers—as compared to non-Hispanic whites. Blacks also had less medication adherence and use of information for dietary decisions, higher HbA1c levels, but fewer problem eating behaviors.

After adjusting for all SES indicators, only the HbA1c disparity and the reverse disparity in problem eating remained. The other disparities disappeared. Said Mayberry, “Socioeconomic factors may largely account for black and white racial disparities in diabetes health behaviors, health literacy, and numeracy, but do not seem to account for disparities in HbA1c.”

“Social factors beyond the individual may influence differences in glycemic control.”

Improving Patient Care

“The data suggest that social factors beyond the individual may influence differences in glycemic control,” Mayberry said. The authors cite racial discrimination in health care, as one example. The study also highlights the value in including detailed social determinants of health in electronic medical records to better understand long-standing health disparities.

Nelson and Mayberry encourage future studies to include more comprehensive markers of SES to understand and improve patient outcomes and ultimately reduce health disparities.