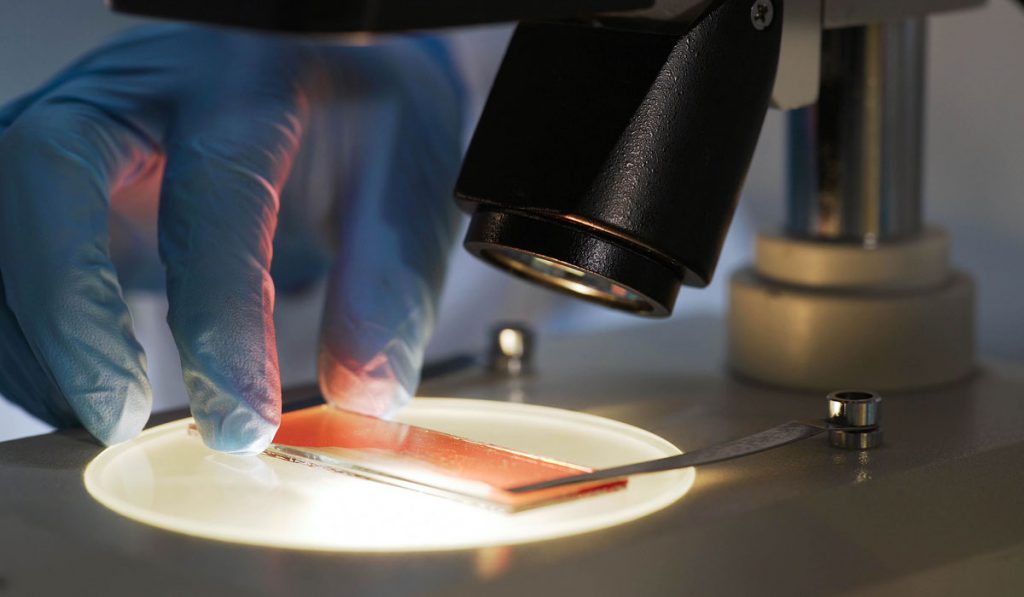

Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) are short nucleic acid fragments that have been shed by cells and remain in circulation. Since tumor cells shed DNA containing the same mutations as the cancer, “liquid biopsies” that test cfDNA in blood may hold promise for detecting and tracking cancers—without the complications and limitations of conventional tissue biopsies.

Ben Ho Park, M.D., co-leader of the Breast Cancer Research Program at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, is directing several research initiatives to assess if liquid biopsies can better inform precision cancer therapies and more quickly assess treatment responses.

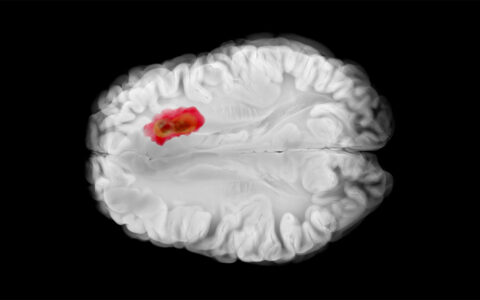

“Tumors are heterogeneous swarms of cancer cells and some cancers are hard to treat because of this heterogeneity,” Park said. “We’re trying to find a better way to monitor the disease, or determine who has microscopic disease using serial blood tests.”

New Measuring Tools

Next generation DNA sequencing has enabled researchers to detect heterogeneous cancer molecules in blood. Research by Park and others confirms that the same genetic mutations in cancerous tissue generally are found in liquid biopsies.

Already, the FDA has approved a liquid biopsy to detect epidermal growth factor receptor mutations associated with non-small cell lung cancer. The test is only approved where a tissue sample is unavailable. Other liquid biopsy tests also are in the pipeline for potential approval.

Park says that there is quantitative value to cfDNA in addition to its potential to identify if a genetic mutation is present, and if there is a targeted drug available.

“The amount of tumor DNA that you have in the cell-free space is in direct correlation with how much disease you have.”

“The amount of tumor DNA that you have in the cell-free space is in direct correlation with how much disease you have,” Park said. “Measuring cfDNA in the blood could provide a non-invasive, cost-effective method for determining tumor burden.”

Informing Treatment

The greatest clinical potential for liquid biopsies may be the ability to spare low-risk patients from unnecessary treatment, Park says.

“The majority of women with early-stage breast cancer are cured with surgery alone. But we don’t have reliable tests to determine who still has microscopic cancer cells circulating that can come back and kill the patient.”

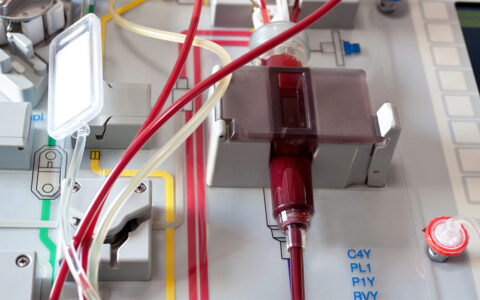

Park helped launch a multi-institutional breast cancer trial, PREDiCTDNA, that is tracking cfDNA in liquid biopsies taken before treatment starts and intermittently during subsequent therapy. The goal is to assess the reliability of cfDNA as a marker indicating which patients have been cured and which patients may need adjuvant therapy.

These liquid biopsies have the potential to provide a much faster answer than the conventional approach of treating, then waiting several months on an imaging test. They may also reveal patients most at risk of metastatic or recurrent disease.

Challenges to Use

Park notes that today’s liquid biopsies still are not as sensitive as tissue samples for the detection of cancer. The concentration of cfDNA in the blood may not be sufficient to detect a driver mutation. And liquid biopsies taken several weeks or months after a tissue sample is obtained may not match the tissue results because of the evolution of the tumor.

Blood samples must also be shipped to reputable companies immediately, and tests must be completed in a matter of days. Insurance reimbursement can be problematic, even in cases where tissue samples are unavailable.

“This field is still in its infancy… we need to be cautious.”

Park argues the prospects for liquid biopsies will come down to clinical utility.

“We have to ensure that we’re offering the best state-of-the-art care and we’re not doing things that have no proven utility, drive up costs and put patients at risk for huge bills,” Park said. “This field is still in its infancy, and we need to be cautious as we gain access to these tests.”