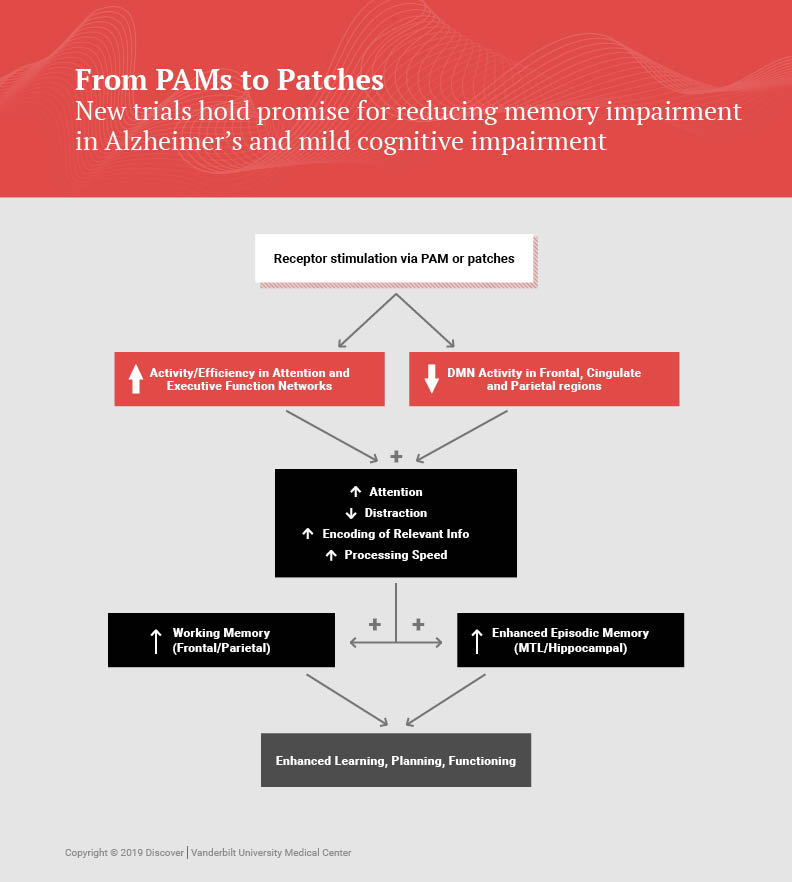

The Center for Cognitive Medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center is leading two clinical trials that may have potential for reducing memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease and related brain disorders. The first is a phase 1, first-in-human trial of a novel small-molecule compound developed at Vanderbilt. The second is a multicenter trial testing transdermal nicotinic stimulation for mild cognitive impairment.

Small-Molecule Compound VU319 Goes to Phase 1 Trial

A potential new drug for Alzheimer’s disease and schizophrenia, developed by scientists at the Vanderbilt Center for Neuroscience Drug Discovery (VCNDD), is now being tested in a first-in-human phase 1 clinical trial. Animal studies suggest that the compound, a small molecule called VU319, may have potential for reducing memory impairments in brain disorders.

The randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, which began in July 2017, is being conducted in about 100 healthy adult volunteers over a period of 12 months to determine the compound’s safety, tolerability and bioavailability when taken orally with or without food.

“This small-molecule approach is a completely new mechanism for potentially treating Alzheimer’s disease.”

“This small-molecule approach is a completely new mechanism for potentially treating Alzheimer’s disease,” said Paul Newhouse, M.D., director of the Center for Cognitive Medicine at Vanderbilt, who designed and is leading the study. “It represents an exciting advance from currently available therapies.”

VU319 is a positive allosteric modulator, or PAM, which enhances the activity of a receptor in the brain. “It’s like taking a new wrench to the receptors,” explained Newhouse.

In this case, the target is the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, which are located on neurons activated by the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. If VU319 passes its human safety trial, the next step would be to test its efficacy in improving cognitive function in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and possibly schizophrenia and other brain disorders.

Previous efforts to stimulate M1 activity directly have failed due to adverse effects, including an abnormally slow heart rate and gastrointestinal distress caused by collateral activation of other muscarinic receptors. Because VU319 selectively augments the native activity of the M1 receptor, it should avoid these effects, the researchers said.

VU319 was developed by a team of scientists at the VCNDD, led by center director Jeffrey Conn, Ph.D., and Craig Lindsley, Ph.D. Research on the potential drug began more than a decade ago. Last November, Conn, Lindsley and their colleagues received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to begin human testing. Conn said this was the first instance he knew of in which an academic drug discovery group has moved a molecule designed to treat a chronic brain disorder from laboratory bench to early clinical trials without a pharmaceutical company partner.

A NIH National Cooperative Drug Discovery/Development grant funded the early basic science and discovery of VU319. The Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation and the Harrington Discovery Institute supported some of the key toxicity studies. The William K. Warren Foundation of Tulsa, Oklahoma, has provided more than $8 million since 2014 to support VCNDD’s development of fundamental new treatments for schizophrenia and other brain disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease.

The Alzheimer’s Association and the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation are supporting Newhouse’s work to test this new molecule.

Repurposing Transdermal Nicotine Patches

Newhouse is also principal investigator for a multicenter trial called the Memory Improvement through Nicotine Dosing (M.I.N.D.) study. Funded by the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, the study is testing whether transdermal nicotine could improve the mild cognitive impairment that is associated with early dementia. Vanderbilt is coordinating with the Alzheimer’s Treatment Research Institute of the University of Southern California to test 200 patients over a two-year period at 30 to 40 sites.

Newhouse has been studying nicotinic stimulation effects on the brain since 1985. An earlier five-year study at three centers tested the nicotine patch in 72 patients over six months of treatment. While taking the patch, patients showed improved attentional and memory performance.

As part of the new M.I.N.D. study, researchers will also be testing biomarkers in a subset of participants through brain scans and spinal fluid extraction. The goal is studying whether nicotine has effects on markers that signal brain atrophy.

“We’re trying to do integrated research on cognitive enhancement by looking at molecules from both directions, discovering and studying new molecules, but also repurposing old ones,” said Newhouse.