With a large proportion of Baby Boomers now 65 years of age or older, and the number of individuals aged 85-plus expected to double in the next twenty years, age-related complexities – multi-morbidity, polypharmacy, frailty, weight loss, cognitive impairment or dementia, disabilities and anemia – have added a new dimension to cardiovascular disease (CVD) care. Add to this the social, financial and psychological dimensions of aging, which only continue to increase as patients get older. As the risk of harm from treatment increases with advancing age, CVD management becomes more challenging.

“Age-associated disease processes and complexities are much more predictive of how well a patient will do after surgery than the presence of heart disease,” said Susan Bell, M.D., assistant professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and director of the geriatric cardiology program at Vanderbilt Heart and Vascular Institute. “A geriatric patient can have as many as 10 disease processes, take 20 to 30 medications, and experience other adverse events. We aim to treat the primary cardiovascular problem, but these other issues must also be considered.”

A Patient-Centered Approach

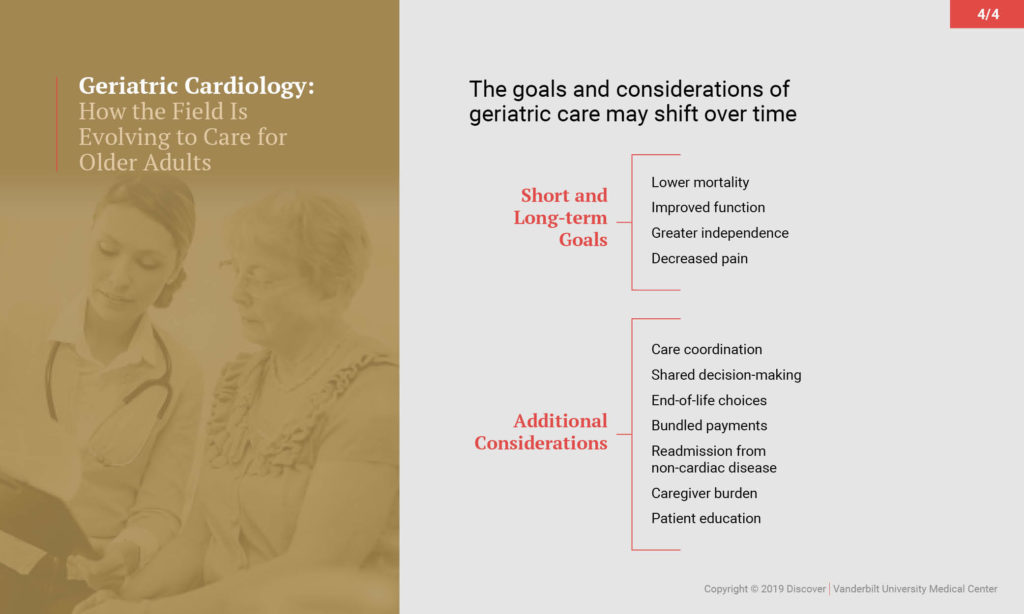

While most cardiologists recognize the problem as a growing concern, there are limited evidence-based standards by which to care for this vulnerable population. At Vanderbilt, Bell and her colleagues assess geriatric patients’ priorities, which may include quality-of-life or functional objectives integral to their realities such as avoidance of dependency and maintenance of independence, the burden of managing multiple chronic diseases, or end-of-life planning. This personalized approach requires more time spent counseling patients about their options.

“Our mandate must be to optimize care,” explained Bell. “As we encounter an aging population, new technologies and changing legislation, cardiology providers must design new processes that are patient-centered and that foster the best care for older patients. Geriatric cardiology is evolving as the appropriate approach for this challenge.”

In collaboration with the Vanderbilt Center for Quality Aging, Bell has worked on studies focused on addressing these issues, including identifying geriatric problems and reducing polypharmacy.

Teaching Geriatric Cardiology

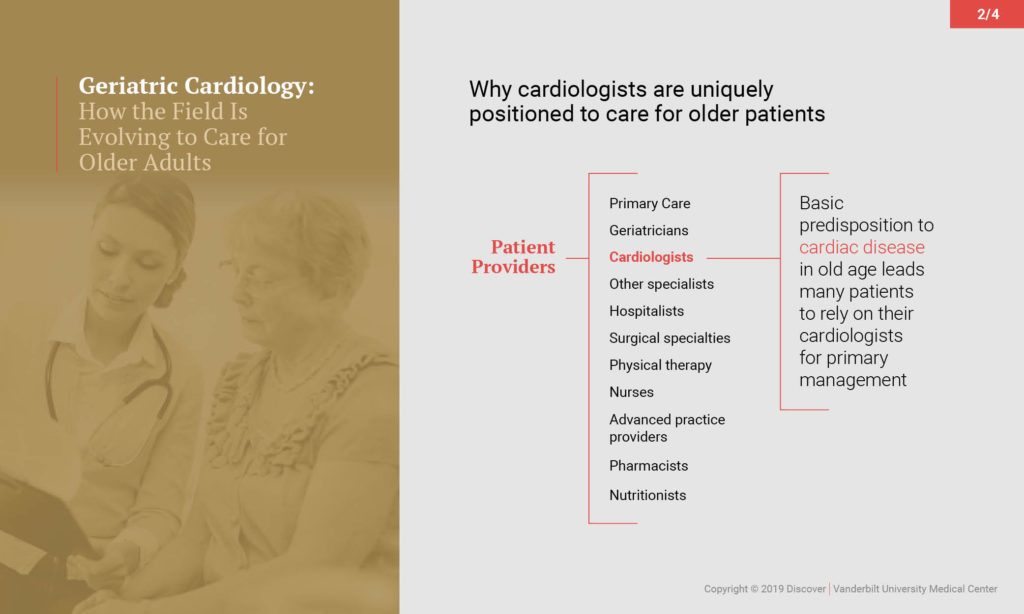

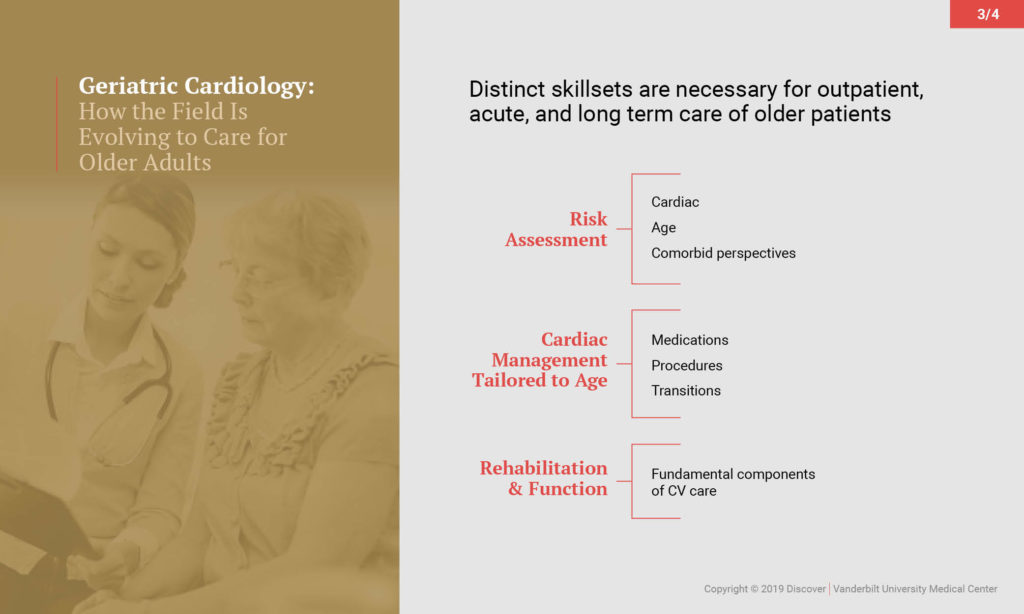

Traditionally, cardiology has embraced the latest technology advancing the field, including cardiac transplant, device therapy and electrophysiology. In the last ten years, a need has emerged for expanded competencies that respond to unmet needs in older CVD patients. These competencies include improved skills in diagnosis, risk assessment, disease management, communications and caregiver support, physical activity and rehabilitation, post-acute care and palliative care and end-of-life decisions.

While cardiology and geriatric medicine are currently different specialties, both the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) are now recommending more training for cardiologists in geriatric medicine. In 2015, Bell, the ACC’s Geriatric Cardiology Section Leadership Council, and national cardiovascular and geriatric medicine experts joined to develop a paper outlining the future of geriatric cardiology and putting forth a Core Cardiovascular Training Statement (COCATS), which includes the following strata:

- Level 1 – Cardiology fellows will learn more about aging processes and polypharmacy in their standard 3-year training.

- Level 2 – A subset of trainees will be trained (during the standard 3-year fellowship) to perform and interpret specific assessments and render specialized care for complex older cardiovascular patients.

- Level 3 – Additional training and expertise acquired beyond the standard 3-year fellowship program will include training and experience within the field of geriatric medicine and palliative care.

Vanderbilt offered the first clinical fellowship in CVD and geriatric medicine supported by ABIM, and this year, geriatric cardiology training will be implemented in several fellowship programs across the U.S.

“We’ve been trying to find ways to broaden the field to incorporate geriatric cardiology: adding an NIH conference to identify gaps in research, finding ways to provide funding for people doing research, developing guidelines for the AHA,” said Bell. “But the most important need is for advanced training.”