Drugs to combat graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic stem-cell transplant have primarily targeted T-cells and B-cells, the body’s frontline immune defenses against foreign invaders.

Now, axatilimab, a monoclonal antibody approved by the FDA in 2024, is breaking through that limitation in an unusual way: by targeting monocytes. Unlike treatments that curb early immune overreaction, axatilimab works over a period of weeks, dampening the response enough to prevent or suppress GVHD in many patients.

Carrie Kitko, MD, medical director of the Pediatric Stem Cell Transplant Program, was Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s site leader for the Phase 2 trial of axatilimab. Her team found that a low-dose level was best for reducing objective measures of organ damage as well as patient-reported symptoms.

“Most of our patients rely too much on steroids to manage symptoms, despite their toxicity,” Kitko said. “Adding a new drug like axatilimab to the handful of FDA-approved agents could help us better fight GVHD and wean them off high doses of steroids.”

Multiple Options Needed

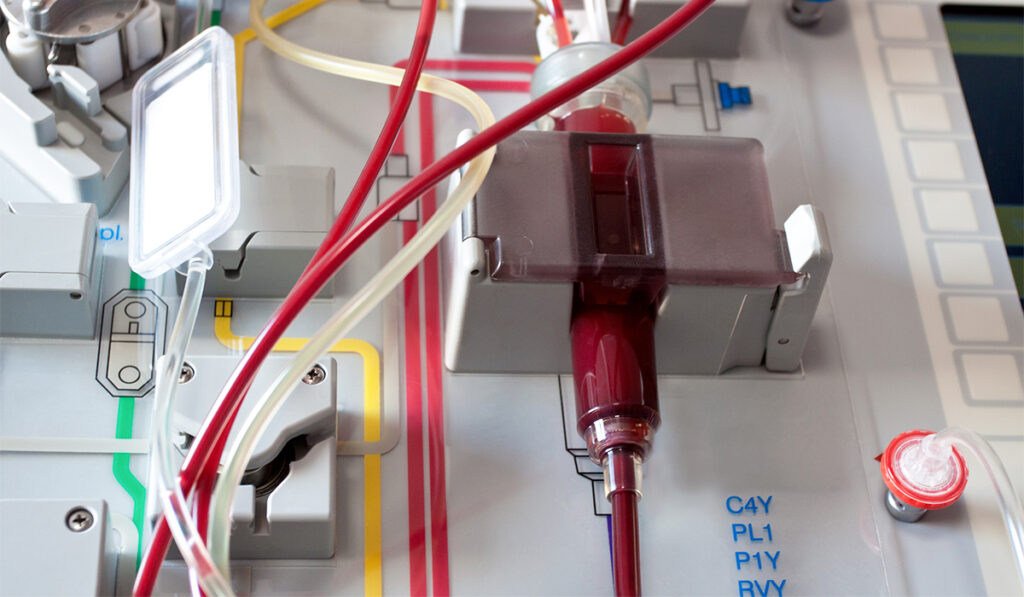

Allogeneic stem-cell transplantation is often used for lymphomas, leukemias, myelodysplastic syndrome and myelofibrosis. The procedure replaces diseased bone marrow with healthy bone-marrow cells from a donor. Some patients with sickle cell anemia or immune deficiencies may also be candidates for bone-marrow transplants.

Yet, 50% to 80% of adults who undergo allogeneic stem cell transplant are affected by graft-versus-host disease, requiring treatment for the inflammation, sclerotic changes and fibrosis affecting multiple organs—most visibly, the skin.

“Even when you have a perfectly matched donor, the risk of getting GVHD is still fairly significant,” Kitko said.

The first year after transplant is the likeliest time to develop GVHD. Treatment typically is a combination of steroids with one of several available agents. Trying to tailor this treatment to each patient’s response amplifies the challenge.

“You may hit a home run with a certain drug in one patient, while another, seemingly similar patient doesn’t respond to that drug at all.”

“Some patients respond beautifully to their first drug, and we don’t really know why,” Kitko said. “It’s frustrating—you may hit a home run with a certain drug in one patient, while another, seemingly similar patient doesn’t respond to that drug at all.”

Partial responses also complicate care.

“Patients may feel better initially, then plateau. So when progress stalls, we switch drugs,” she said. “Having another solid alternative to try is invaluable.”

Lower Doses Superior

Axatilimab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor signaling to reduce inflammation and fibrosis in recurrent or refractory graft-versus-host disease. It targets both monocytes and macrophages—key immune modulators alongside T-cells and B-cells.

In the Agave 201 study of axatilimab, researchers randomized 241 patients with GVHD into three cohorts. While most of the participants were adults, some pediatric patients were included. Each cohort received a different dose by intravenous infusion over six cycles: either 0.3 mg/kg every two weeks, 1.0 mg/kg every two weeks or 3.0 mg/kg every four weeks.

Other immunosuppressants were limited to only corticosteroids, a calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus and cyclosporine) or an mTOR inhibitor like sirolimus.

Using the National Institutes of Health consensus criteria, researchers scored changes in eight organs to track improvement, stability or progression. The overall response rate was 74% in those receiving doses of 0.3 mg/kg every two weeks, compared to 67% for those receiving the 1.0 mg/kg dose and 50% for those receiving 3.0 mg/kg every four weeks.

On the modified Lee Symptom Scale, a measure of patient symptom burden as assessed by the patients, 60%, 69% and 41% of patients in the respective groups reported a drop of over five points, demonstrating a clinically meaningful improvement.

“The higher-dose group had a more prolonged decrease in the monocyte count compared in the lower dose group,” Kitko said. “This suggests that drastically reducing these immune cells long-term has downstream effects. A strategy of modest reduction, followed by recovery before you knock their immune system down again, might work better—something future studies should explore.”

Safe Use

Liver enzymes rose in most patients, but Kitko says this didn’t result in organ injury.

“It is likely a response to axatilimab’s lowering of Kupffer cells, which metabolize some of the normal enzymes we produce,” she said.

Periorbital swelling affected up to 29% of the high-dose patients, but it was found in less than 3% of the 0.3 mg/kg group.

Combination Therapies

Kitko sees the potential for combining agents that target different immune cells.

“Their mechanisms differ, so there’s hope for synergy,” she said. “A well-designed trial could confirm this.”

Pinpointing the right drug—or mix of drugs—for each patient hinges on identifying blood or tissue markers, a top research priority.

“For now, axatilimab’s addition strengthens our arsenal in fighting the GVHD threat,” Kitko said.