Short- and long-term cardiotoxicity is a threat that looms large for cancer patients, with as many as 44 percent of adults and 30 percent of children experiencing some level of heart damage as a result of their treatment regimen.

For children, the stakes are even higher, as they are seven times more likely than adult patients to die from their cardiac impairment, even decades after the course of treatment.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center and Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt were early to the table in forming a cardio-oncology working group and clinic to focus on the issue, leading to clinical guidelines for monitoring and mitigating cardiac sequalae. In the early 2010s, they launched a cardio-oncology fellowship program, one of just a handful in the country.

With a cardiac screening timeline already in place for cancer patients at Vanderbilt, the team began asking whether families of patients should be more deeply engaged and examined other practices for best management of cardiomyopathy.

“Could we also provide a little more context, and explain to families why anthracyclines can cause cardiomyopathy, what might happen if they were to develop cardiomyopathy, and do more to offer heart healthy recommendations?” said Scott Borinstein, M.D., Ph.D., the Scott and Tracie Hamilton Chair in Cancer Survivorship and director of pediatric hematology/oncology.

Borinstein, who assumes the role of medical director for the pediatric heart transplant program in mid-2023, and David Bearl, M.D., medical director of the Pediatric Ventricular Assist Device Program, are the pediatric representatives for the cardio-oncology working group.

Culprits in Cardiotoxicity

“Children receiving cancer treatment have a seven times higher risk than adults of cardiac death,” Bearl said. “They can develop cardiomyopathy or heart failure 20 to 30 years after receiving the cancer treatment.”

Certain drugs are known for higher potential cardiac side effects, which may include arrhythmias, hypertension, cardiomyopathy and heart failure. The team is probing how best to mitigate the long-term risks of arrhythmia, hypertension, cardiomyopathy and heart failure during cancer treatment.

“Anthracyclines are very effective chemotherapy agents,” Borinstein said. “We’ve used those for many different types of cancer, from high doses in bone and soft-tissue sarcomas to lower doses in leukemia, liver and kidney cancers. But anthracyclines, as well as some of the tyrosine kinase inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors, also can have adverse effects on the heart.”

One of the most dangerous drugs for the heart is carfilzomib, known to be effective in treating multiple myeloma, with over half of patients treated having cardiovascular sequalae. For these patients, close monitoring of natriuretic peptides is important and may drive changes in treatment dosages, infusion rates and surrounding care.

Lowering Risk

Criteria have not been well established for predicting who will develop cardiomyopathy or heart failure. However, there may be clues based on post-treatment echocardiography. Bearl said patients who have had high doses of anthracyclines sometimes have smaller overall cardiac mass and thinner ventricular walls.

“Whether that’s going to result in in cardiomyopathy down the line or not, we don’t know yet,” he said. “But it is a significant observation we will continue to track through these routine follow-ups.”

Bearl cautions that lowering the chemotherapy dosage while adding chest radiation does not generally lower risk, with radiation therapy sometimes leading to an ischemic type of cardiomyopathy.

Treatment Strategies

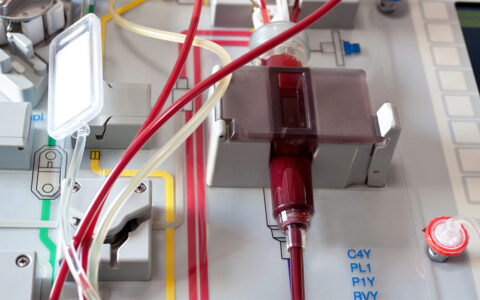

Particularly for patients on anthracyclines, referral to a cardio-oncology clinic and monitoring with an echocardiogram or cardiac MRI are standard during treatment. The Monroe Carell team looks primarily at ejection fraction and fractional shortening, but also more advanced techniques including tissue Doppler and strain. In some cases, an ECG may provide additional information.

“Occasionally, kids will have had early cardiotoxicity, which requires us to alter their treatment plans to avoid further heart damage,” Borinstein said.

Such scenarios call for a multidisciplinary discussion of the risks and benefits of continuing treatment.

Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity can be minimized by both limiting the lifetime cumulative dose of these chemotherapy agents and co-administering the cardio protectant medication, dexrazoxane.

“We hypothesize that rigorous dose management and dexrazoxane use will effectively minimize effects on the heart that may not materialize for decades after receiving chemotherapy,” Borinstein said. “It is a game-changer for our cancer survivors, who now often live over 50 years or longer after their cancer treatment.”

Safer Alternatives to Come

On the preventative front, Borinstein points to new immunotherapy drugs such as blinatumomab that are being used to treat leukemia.

“We are walking the tightrope between giving adequate treatment for cure – which has to be number one – and excessive cardiac risks.”

“This is exciting, because they may allow a decrease in the use of cardiotoxic drugs a child receives, thus decreasing long-term side effects,” he said.

“In the meantime, we are walking the tightrope between giving adequate treatment for cure – which has to be number one – and excessive cardiac risks.”