A new study in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology finds that in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction presents prior to initiation of maintenance hemodialysis. The findings suggest that improving mitochondrial function may be a strategy to prevent or treat frailty and sarcopenia in this patient population.

“Frailty and sarcopenia are associated with higher morbidity and mortality in patients with advanced CKD, yet there is no successful intervention to prevent frailty and sarcopenia from developing,” said Jorge Gamboa, M.D., first author on the study and a research assistant professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

“The final goal is to find therapeutic targets to prevent frailty and sarcopenia, and we think mitochondrial function may be a potential target,” Gamboa said.

“The final goal is to find therapeutic targets to prevent frailty and sarcopenia, and we think mitochondrial function may be a potential target.”

Mitochondrial Dysfunction

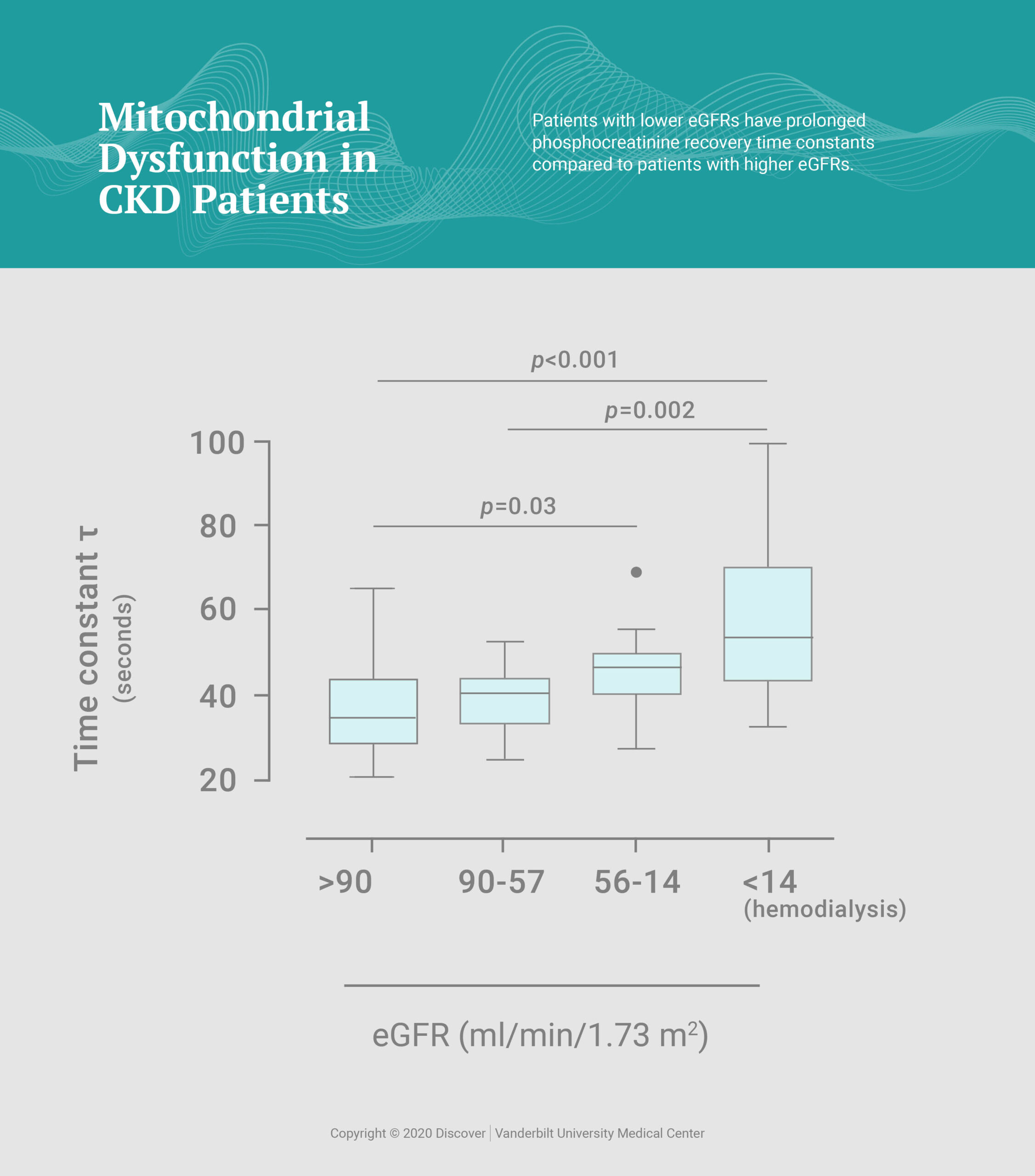

A total of 63 participants in the study were divided into three groups: 21 patients with no history of CKD, 20 with CKD (stages 3-5) not on maintenance hemodialysis, and 22 with end-stage kidney disease on maintenance hemodialysis.

As an indicator of mitochondrial function, the study assessed phosphocreatine (PCr) recovery kinetics, reporting prolonged PCr recovery constants in patients on maintenance hemodialysis (53.3 seconds, median) as well as patients with CKD stages 3-5 not on maintenance hemodialysis (41.5 seconds) compared to healthy participants (38.9 seconds). Further stratification of patients by estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) revealed a significant correlation between longer PCr recovery constants and lower eGFRs.

“This indicates that mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with severity of CKD and starts prior to the initiation of maintenance hemodialysis,” Gamboa said.

“Mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with severity of CKD and starts prior to the initiation of maintenance hemodialysis.”

Mitochondrial dysfunction was also associated with poor physical performance as well as greater intermuscular adipose tissue, which can impair mobility, and increased markers of inflammation and oxidative stress, key contributors to mitochondrial dysfunction.

“It seems that mitochondria are damaged somehow – it can be by uremic toxins, oxidative stress, or inflammation, all of which can be induced by CKD – and that probably leads to physical dysfunction, sarcopenia and frailty,” Gamboa explained. “More studies must be done to elucidate the primary mechanisms leading to these interconnected metabolic abnormalities.”

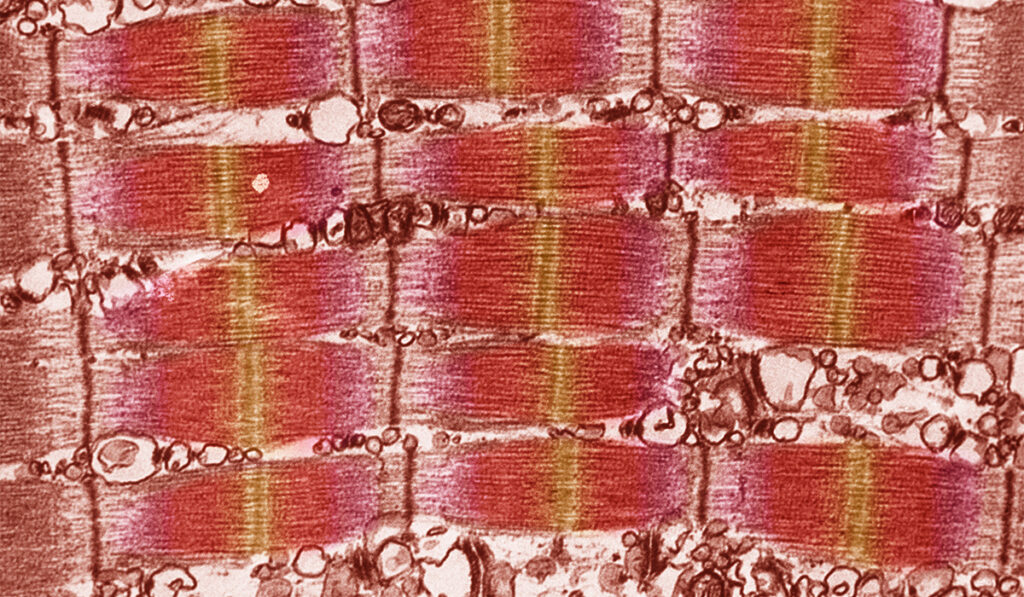

Already, Gamboa and others have begun to outline specific structural and functional changes in mitochondria from CKD patients.

Preventing Sarcopenia

Gamboa and colleagues are now thinking about interventions to slow the progression of frailty and sarcopenia in CKD patients. While exercise-based interventions are successful at preventing frailty and sarcopenia in the general population, Gamboa points out that CKD patients are less responsive to the benefits of exercise.

“There is something that has not yet been identified that leads to poor exercise response in CKD,” Gamboa said. “Our next step is to see if we can target mitochondria and exercise at the same time to improve the response to exercise in CKD patients.”

“It’s more than improving physical performance,” Gamboa adds. “Once these patients can be independent, their whole quality of life improves.”