Key Takeaways

- Targeting DBS to M1/SMA and avoiding pre-SMA is associated with slower motor progression in early-stage patients.

- Stimulation outside of the target area led to a similar course of motor progression as control subjects on standard therapy.

- Advanced-stage Parkinson's patients also experienced improvements in motor symptoms from highly targeted DBS.

Treatment for Parkinson’s disease has long been a matter of mitigating symptoms over an inevitable course of functional deterioration, with patients typically having some combination of movement, cognitive and behavioral symptoms.

Now, for the first time, the ability to slow progression or even bring it to a standstill is proving possible through deep-brain stimulation (DBS) that precisely targets the confluence of certain nerve fibers in the brain.

Working with a team led by deep brain stimulation expert David Charles, M.D., neurology researcher and first author Mallory Hacker, Ph.D., M.S.C.I., demonstrated that the positive benefits of that targeted stimulation can extend across years of DBS in patients with advanced-stage disease.

“Working with our Harvard colleague, we assessed an independent cohort of 29 patients who started deep-brain stimulation at an advanced stage,” Hacker said.

“After an average of 5.5 years of DBS, there was significant variance in their motor function changes, as expected in Parkinson’s disease.”

However, the team also found that this variance strongly correlated with whether the patient was receiving stimulation of M1/SMA primary motor and supplementary motor areas along with avoidance of the pre-supplementary motor region.

First Study Identified Locale

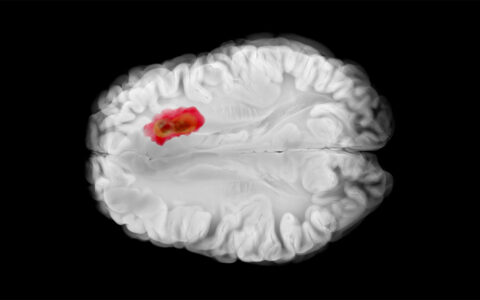

In Parkinson’s disease, deep brain stimulation is an adjunctive therapy to medications that temper symptoms. Stimulation targets the subthalamic nucleus, a small lens-shaped area that lies within the basal ganglia system and receives input from many brain areas, including the primary motor area and the supplementary motor areas within the dorsolateral subthalamic nucleus.

In 2023, Hacker and her team published findings demonstrating that stimulation of a specific location and certain fibers within the dorsolateral subthalamic nucleus may slow or stop disease progression in early Parkinson’s.

“We may be seeing the treated brain undergoing lasting changes in neural connections and activity patterns in response to the sustained stimulation.”

Stimulating the primary motor area and the supplementary motor areas near the dorsolateral subthalamic nucleus region has been previously associated with symptomatic motor improvement in Parkinson’s. Importantly, however, Hacker and her team also discovered a negative relationship between stimulation of the pre-supplementary motor area and patient outcomes.

In some individual cases, they found that stimulation further outside the dorsolateral subthalamic nucleus was associated with increasingly worse motor progression, per the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale III. In fact, subjects with contacts outside the dorsolateral thalamic nucleus appeared to follow a similar disease course to that of the control group assigned to optimal drug therapy alone.

Those receiving treatment in the stimulation “sweet spot” required less medication over time and responded to lower stimulation voltages.

“Taken together, these studies suggest a unique connectivity profile of stimulating specific fibers and avoiding others as a way to understand and predict long-term benefit across Parkinson’s disease,” Hacker said.

Mechanism-of-Action Examined

Exactly how this targeted stimulation might slow motor progression remains unclear, Hacker said, but there is evidence of improved long-term plasticity within the sensorimotor network.

“We may be seeing the treated brain undergoing lasting changes in neural connections and activity patterns in response to the sustained stimulation,” she said.

While these studies both examined the relationship between stimulation in specific sites and motor outcomes, subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation has been shown to impact a range of non-motor symptoms as well, including verbal fluency and depression.

“It will be important for future research to explore the potential influence of the stimulation site on other clinical outcomes as well,” Hacker said.