Over 40 percent of gynecologic oncology patients receive aggressive end-of-life care, yet only about half have a palliative-care consultation that encourages drawing up advance directives.

Gynecological oncologist Alaina J. Brown, M.D., M.P.H., spearheaded a year-long initiative carried out by a team of medical students at Vanderbilt University Medical Center to encourage hospitalized gynecologic cancer patients to complete an advanced directive for use as a reference when death is imminent.

“The absence of advance directives for patients can lead to stresses on the patients’ families and our social workers, and it leads to more expensive care,” Brown said. “The process is made significantly easier if the patient has laid out their wishes before the end of their life.”

Plainspeak Preferred

End-of-life care planning gives the patient a chance to outline their preferences regarding ongoing treatment for their disease, types of resuscitation efforts desired, approved life support technology, types of pain relief, and options for hospice. It also allows the patient to choose a surrogate to make decisions on their behalf when they are no longer able to do so. An advance directive seeks to clearly define the patient’s preferences. Tools may include a living will, medical power of attorney, and portable medical orders for specific medical treatments.

“An absence of advance directives for patients can lead to stresses on the patients’ families and our social workers and leads to more expensive care.”

Previous studies have shown benefits of an advanced-care packet organized as a letter instead of the more traditional business-style form, including greater concordance between a patient’s wishes and the care they ultimately receive.

The document used in the project was based on the Stanford Letter, a worksheet guiding patients through all aspects of end-of-life care. The Stanford Letter was designed to minimize fear by using less sterile, legalistic terminology and its conversational tone helps the patient more directly outline their preferences for decisions surrounding their death, the researcher said.

Conversation Starters

In the study, Brown asked Vanderbilt medical students to visit gynecologic cancer inpatients and walk them through the letter-based advanced care process. Many of these patients had advanced stage cancer and discussions surrounding end-of-life care were considered delicate.

The medical students were trained to be sensitive to the patient’s non-verbal cues – knowing when to back off as discussions become uncomfortable and assuring patients they may choose whether or not to complete the process.

Conversation prompts included in the worksheet were statements such as:

“Here is what matters most to me.”

Examples are: Being at home, doing gardening, traveling, going to church, playing with my grandchildren.

And, “here is how we make medical decisions in our family.”

Examples are: I make the decision myself, my entire family has to agree on major decisions about me, my daughter, who is a nurse, makes the decisions, etc.

Vanderbilt’s MyHealth app also makes an advanced planning directive available to patients. A message with a corresponding link is sent to patients after hospital admission for easy access to the documents.

Consultations Effective

After offering the advanced care letter, 55 of 168 of hospitalized gynecological cancer patients, or 33 percent, had advanced directive documentation listed their EMR. This was compared to a pre-implementation cohort of 26 percent.

“This 27-percent relative increase suggests that a one-on-one conversation and worksheets that are in reader-friendly language may be an effective approach worth expanding,” Brown said.

The study team also reported that older age and positive marital status were associated with increased likelihood of having an advance directive in the chart.

DNR Considerations

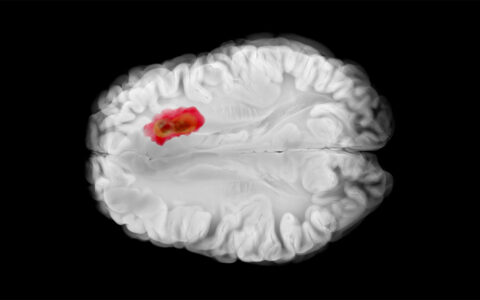

Issues that arise when brain death occurs include the question of mechanical ventilation and other factors that may be particularly traumatic for family members, Brown said.

A living will traditionally has been the primary documented reference for end-of-life preferences on behalf of a patient who is incapacitated. However, a “do not resuscitate” order may be added to explicitly prohibit cardiac resuscitation.

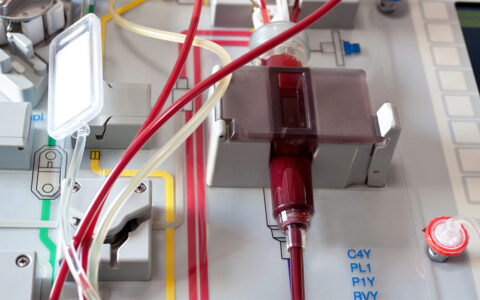

A best-case scenario for cardiac resuscitation involves patients who are young and healthy. But even then, success occurs only half the time, Brown said. For older, terminally ill cancer patients, the chances are much lower – and then may deliver dubious benefits.

“Even if we can restore a measurable heartbeat, it is likely they would require some sort of prolonged additional ICU level support like intubation and ventilation,” Brown said. “Unfortunately, despite heroic efforts, they will still have the underlying issue – which is incurable cancer. So, it’s important for patients to consider ahead of time the low likelihood of recovery to their prior health status.”