Featured in the Vanderbilt Eye Institute Impact Report 2024. Peruse the rest of the Impact Report here.

Racial and ethnic minority populations are traditionally underrepresented in genetic repositories, genome-wide association studies, and prediction models, contributing to the persistence of health disparities across groups.

Two new National Institutes of Health-funded studies at the Vanderbilt Eye Institute led by Dolly Ann Padovani-Claudio, M.D., Ph.D., aim to address this problem from radically different perspectives.

The first, a collaboration with the University of Texas and the University of North Carolina, will explore longitudinal biological data from Hispanic/Latino individuals near the U.S. — Mexico border. They hope to better understand the mechanisms of disease in diabetic retinopathy and pursue new biomarkers and drug targets for its management.

The second study builds on previous work at Vanderbilt University Medical Center to develop PheCodes, a coded language that helps track and map out diseases or phenotypes, which are human traits influenced by both our genes and our environment. Padovani-Claudio will help to optimize this phenome code and structure to better use data from electronic health records (EHRs) for research, particularly developing “iPheCodes” for vision research.

“These projects will enhance our ability to leverage biobank and EHR data to explore ophthalmic disease patterns, associations, and disparities with results that are reliable, reproducible, and generalizable,” she said.

Using Biobanks to Track Disease

Padovani-Claudio’s early research explored the impact of chemokine signaling in the brain’s myelin. Chemokines are elevated in the eyes of patients with diabetic retinopathy, and her lab found decreased retinopathy in mice with either chemokine receptor mutations or drug inhibition. Her next question: What about in humans?

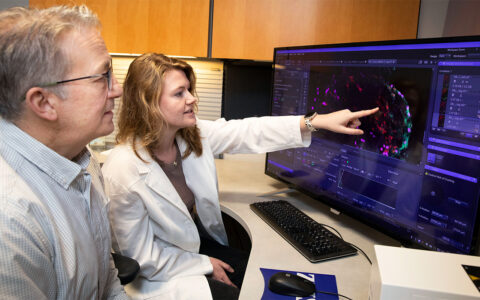

Diabetic retinopathy exhibits very prominent disparities, Padovani-Claudio noted. Using Vanderbilt’s BioVu biobank and its Synthetic Derivative de-identified EHR database, she discovered gene variants in chemokine receptors to be associated with worse retinopathy, but only in a subset of individuals.

“I tried to explore other similar associations, but when I looked at Hispanic adults, I found this group was a minuscule proportion of the adult patients followed for eye disease at Vanderbilt,” she noted.

“The findings reinforced the power of using the EHR to link what we see in the clinic and what we do in the lab.”

Padovani-Claudio was attending a conference when she met Jennifer “Piper” Below, Ph.D., a professor at the Vanderbilt Genetics Institute, who works with a team from the University of Texas studying associations between blood biomarkers and cardiometabolic disease, one of the biggest predictors of retinopathy. That team had been following a group of patients at the Mexican border for more than a decade – taking blood samples and functional measurements and screening for social drivers of health. Additionally, they were capturing images of the study participants’ eyes.

“This community is very trusting of the clinical research team striving to understand the diseases that affect them most,” Padovani-Claudio said.

The team also partners with a federally qualified health center to enhance care, she added.

“The strong bond and trust between the researchers, community, and health care providers facilitates research into their diseases, co-morbidities, and risk factors.”

“These projects will enhance our ability to leverage biobank and EHR data to explore ophthalmic disease patterns, associations, and disparities with results that are reliable, reproducible, and generalizable.”

Padovani-Claudio saw this as an opportunity to learn what is behind Hispanic patients’ predisposition to worse retinal disease. The new NIH study will help her team distill transcriptome and metabolic profiles from blood samples, while the imaging will help identify participants with and without retinopathy.

Padovani-Claudio and Below will be co-leading the study with Kari North, Ph.D., from the University of North Carolina, and Susan Fisher-Hoch, M.D., from the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

“We will use statistical genetics and computing to assess whether particular blood profiles of patients with diabetic retinopathy are a cause or a consequence of the disease,” she said.

In an ideal future, a simple blood test screening would allow clinicians to quantify the risk of blinding retinopathy, and both inform the need for examinations and guide management, Padovani-Claudio explained. “For those with limited access to regular health care such a tool would be particularly impactful.”

“By including them in groundbreaking research, we hope these patients will equally benefit from scientific advances and new therapies.”

Expanding the Breadth of EHRs

For years, the medical community has used international disease classification codes (ICD) to note diagnoses in patient health records. PheCodes, created by Lisa Bastarache, Ph.D., and colleagues in the Vanderbilt Department of Biomedical Informatics, define combinations of ICD codes used to study phenome associations.

“However, the early PheCode hierarchical structure lacks the detail required to accurately identify many sight-threatening conditions,” Padovani-Claudio said. “For instance, the general term ‘glaucoma’ refers to all patients who have glaucoma and all who are suspects. By lumping them together, you’re not going to find associations.”

In their second study, Padovani-Claudio and her team will work to create a more granular version of eye PheCodes to enhance association studies using EHRs. The aim is to allow unrestricted exploration of any disease or phenotype as a potential cause or consequence of others.

“This is the beauty of these types of collaborations. Not only will we be democratizing the ability to do these studies, but we’ll be training the next generation of researchers.”

The Vanderbilt team plans to test the new iPheCode definitions using diverse biobanks to support new and evolving studies of eye-related diseases and uncover health disparities. They will share the iPheCode definitions and algorithms for others to use.

“We’re also providing an opportunity for students interested in medicine or ophthalmology to help us sort through the EHRs, look at ICD codes, and determine who really has each disease and who doesn’t,” Padovani-Caludio noted.

“This is the beauty of these types of collaborations. Not only will we be democratizing the ability to do these studies, but we’ll be training the next generation of researchers in the process.”