The central mission of the heart transplant community is to save lives in patients with advanced heart disease, and within this effort, there is an ongoing need to expand a perpetually insufficient supply of donor hearts.

To do so, many transplant centers have adopted donation after cardiac death (DCD) hearts, an addition to those traditionally donated after brain death (DBD). As the donor pool widens, transplant teams must reevaluate practices for preserving the health of the donated heart, especially during an expanding gap of time between organ recovery and transplant.

To gain more clarity on the question, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, the world’s leading heart transplant center, is a key participant in a nationwide, non-randomized study of the XVIVO organ preservation system.

“We have recently seen a real renaissance in our ability to use technologies that allow us to recover organs from further distances, with the potential to have fewer early-organ problems and to expand the donor pool,” said site principal investigator Ashish Shah, M.D., chair of the Department of Cardiac Surgery and medical director of transplant surgery at Vanderbilt.

Introduced approximately five years ago, the XVIVO system focuses on perfusing whole organs, which contrasts with the traditional static cold-storage method. In some cases, extended storage can make the difference.

“As a world-leading transplant center, we are continually looking at novel ways to recover hearts,” Shah said. “Now, we’re working with other key transplant centers to elucidate the risks and benefits of the XVIVO perfusion device that has shown superior outcomes over traditional cold storage in Australia and Europe.”

Christopher Schwartz, R.N., Vanderbilt’s organ recovery coordinator and an integral member of the transplant study team, describes the limits on travel distance the traditional cold storage imposes.

“We have had a four-hour window with the common method of static ischemic transportation, where the heart is in a cooler without any blood or oxygen-rich components flowing through it,” he said. “The XVIVO method may extend that window to as many as nine or 10 hours.”

Advantage of Time

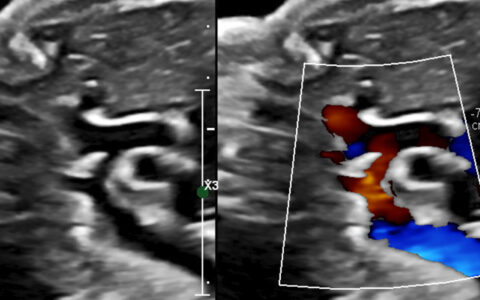

In traditional cold storage, the heart is preserved on ice at 0-4 C, without added nutrients or blood flow. In contrast, XVIVO’s closed-loop system, first introduced for lung transplantation, perfuses the heart with a continuous flow solution of oxygenated hypothermic fluid at 8 C.

In December 2023, Vanderbilt performed the first transplant of a DCD heart using the XVIVO system. To date, Shah says, the patient is thriving, free of graft dysfunction.

“Intuitively, the combination of a healthier organ from DCD recovery and oxygen and nutrients flowing through the organ should improve outcomes,” Schwartz said. “We need to test that out here in the largest transplantation community in the world.”

Leading Centers Join

The PRESERVE trial will enroll 141 patients across leading transplant centers in the U.S.

Importantly, hearts from donors with “extended criteria,” which are higher risk because of older age, thickened heart walls, or longer traveling distances, are included in assessing clinical safety.

“We want to evaluate the XVIVO device across a broader swath of potential donors than the community has been comfortable transplanting in the past,” Shah said.

Primary endpoints include health of the organ and primary graft dysfunction at 30, 60 and 90 days post-transplant, with patients followed for up to one year.

“If the trial bears out that the hearts can be recovered safely with a very low rate of early allograft problems, we will have more time and, therefore, a wider geographic band of accessibility,” Shah said.

“It opens the door to ask some really interesting questions about how we can expand the donor pool, including more immunologic matching for genetic compatibility and better heart-size matching.”

Finally, Shah says the trial has implications for organ allocation in general, potentially moving the donor organizations from local, regional and national allocation to continental or even worldwide allocation.

Growing the Pool

Prior to 2020, Vanderbilt only transplanted organs from donors who have experienced brain death. Like DCD donors, DBD donors have undergone non-recoverable neurologic injury, but they have not yet reached formal brain-death criteria.

A Vanderbilt study published in October 2023 found no difference in one-year survival and other outcomes among DBD and DCD heart recipients. Today, about half of heart transplants at Vanderbilt use DCD organs and Shah says that widespread use of DCD hearts could expand the national donor pool by more than 20 percent.

Vanderbilt’s transplant team now uses thoraco-abdominal normothermic regional perfusion, an in situ DCD method that maintains nutrient flow to the heart after death, buying additional time before transport, Shah said.

“Learning the risks and benefits of each transport storage system will help define the optimal journey from donor to recipient in both DCD and DBD hearts over various travel distances.”

“This enables us to use organs that were previously discarded because they were determined to be too injured and at too high a risk for subsequent problems,” he said.

This type of perfusion will remain relevant as newer methods are explored.

“Learning the risks and benefits of each transport-storage system will help define the optimal journey from donor to recipient in both DCD and DBD hearts over various travel distances,” Shah said. “This will be a continually shifting analysis as we find new ways to make more organs patient-ready, avoid rejection risk, and safely implant hearts that have sustained some damage.”